“Your story is your life,” says Peter. As human beings, we continually tell ourselves stories — of success or failure; of power or victimhood; stories that endure for an hour, or a day, or an entire lifetime. We have stories about ourselves, our creative business, our customers ; about what we want and what we’re capable of achieving. Yet, while our stories profoundly affect how others see us and we see ourselves, too few of us even recognize that we’re telling stories, or what they are, or that we can change them — and, in turn, transform our very destinies.

Telling ourselves stories provides structure and direction as we navigate life’s challenges and opportunities, and helps us interpret our goals and skills. Stories make sense of chaos; they organize our many divergent experiences into a coherent thread; they shape our entire reality. And far too many of our stories, says Peter, are dysfunctional, in need of serious editing. First, he asks you to answer the question, “In which areas of my life is it clear that I cannot achieve my goals with the story I’ve got?” He then shows you how to create new, reality-based stories that inspire you to action, and take you where you want to go both in your work and personal life.

Our capacity to tell stories is one of our profoundest gifts. Peter’s approach to creating deeply engaging stories will give you the tools to wield the power of storytelling and forever change your business and personal life.

Join Peter for a truly transformational vacation for the mind.

Practical Info

Tour Details:

- Duration: 5 days

- Start Time: 09:30 AM

- End Time: 5:00 PM

- Cost: € 3.450 per person excluding VAT (there are special prices for two or more persons)

You can book this tour by sending Peter an email with details at peterdekuster2023@gmail.com

TIMETABLE

09.40 Tea & Coffee on arrival

10.00 Morning Session

13.00 Lunch Break

14.00 Afternoon Session

17.00 Drinks

What Can I Expect?

Here’s an outline of The Hero’s Journey in French Cinema in Paris

Journey Outline

OLD STORIES

- The Power of your Story

- Your Story is Your Life, Your Life is Your Story

- What is Your Story?

- Your Hero’s Journey

- Is It Really Your Story You Are Living?

- Old Stories (stories about you, your art, your clients, your money, your self promotion, your happiness, your health)

- Tell your current Story

YOUR NEW STORY

- The Premise of your Story. The Purpose of your Life and Art

- The words on your tombstone

- You ultimate mission, out loud

- The Seven Great Plots

- The Twelve Archetypal Heroes

- The One Great Story

- Purpose is Never Forgettable

- Questioning the Premise

- Lining up

- Flawed Alignment, Tragic Ending

- The Three Rules in Storytelling

- Write Your New Story

TURNING STORY INTO ACTION

- Turning your story into action

- Story Ritualizing

- The Storyteller and the art of story

- The Power of Your Story

- Storyboarding your creative process

- They Created and Lived Happily Ever After.

About Peter de Kuster

Peter de Kuster is the founder of The Heroine’s Journey & Hero’s Journey project, a storyteller who helps creative professionals to create careers and lives based on whatever story is most integral to their lives and careers (values, traits, skills and experiences). Peter’s approach combines in-depth storytelling and marketing expertise, and for over 20 years clients have found it effective with a wide range of creative business issues.

Peter is writer of the series The Heroine’s Journey and Hero’s Journey books, he has an MBA in Marketing, MBA in Financial Economics.

The Power of Your Story

What do I mean with ‘story’? I don’t intend to offer tips on how to fine-tine the mechanics of telling stories to enhance the desired effect on listeners.

I wish to examine the most compelling story about storytelling – namely, how we tell stories about ourselves to ourselves. Indeed, the idea of ‘one’s own story’ is so powerful, so native, that I hardly consider it a metaphor, as if it is some new lens through which to look at life. Your story is your life. Your life is your story.

When stories we watch touch us, they do so because they fundamentally remind us of what is most true or possible in life – even when it is a escapist romantic story or fairy tale or myth. If you are human, then you tell yourself stories – positive ones and negative, consciously and, far more than not, subconsciously. Stories that span a single episode, or a year, or a semester, or a weekend, or a relationship, or a season, or an entire tenure on this planet.

First Location: Hotel Lutetia

Hotel Lutetia itself is a living example of how “your story is your life, your life is your story” – a place that has had to rewrite its own identity more than once. Opened in 1910 as a glamorous Left Bank palace for Le Bon Marché’s affluent shoppers, it was designed as a house of conversation and creativity rather than just accommodation, a hub where artists, writers, and visionaries like James Joyce and Picasso stayed and worked. During the world wars, however, this elegant Art Nouveau landmark became something very different: a Red Cross hospital in World War I and, in World War II, first a site linked to occupation and then, after liberation, a reception center where thousands of emaciated concentration camp survivors arrived, and where families came daily to read the lists on the walls, hoping a loved one’s name had appeared.

For your Hero’s Journey leadership walking tour, you can frame Lutetia’s story as a powerful mirror of the inner story-work you invite participants into. On the outside, the building appears continuous and stable, but its inner life has moved through archetypal stages: innocence and optimism, ordeal and shadow, and finally a painful yet hopeful rebirth as a place of reunion and resilience. It shows how a “setting” – like a hotel, a role, or a career – can carry contradictory narratives at once: luxury and trauma, brilliance and brokenness, public grandeur and private grief.

You might tell it like this at the start point:

“Here at Hotel Lutetia, Paris wrote one of its most revealing self-stories. This began as a temple of elegance for the city’s confident bourgeoisie. Then war came, and these same halls became a ward for wounded soldiers. Later, during and after the Second World War, Lutetia held both darkness and light: associated with occupation, then transformed into a place where survivors returned in striped uniforms, and where families scanned lists of names to discover whether their story ended in loss or in reunion. In one building, we see what happens when a ‘story about ourselves’ meets reality: it cracks, it complicates, and, if we let it, it deepens.

As you stand here, ask yourself:

- What is the ‘hotel façade’ story you present to the world about who you are as a leader?

- What unspoken chapters—wounds, failures, loyalties—live behind that façade?

- Where has your own story moved from comfort to crisis, from occupation by other people’s expectations to liberation?

- Who was waiting at your inner ‘Lutetia lobby’—hoping you would return from a difficult season changed, but alive?

- If your life were this building, what new chapter are you ready to write in its history?”

In this way, Lutetia becomes a starting altar for the tour: an external narrative that illustrates the inner truth you describe—that we are always, consciously and subconsciously, authoring multi-layered stories about who we are, across episodes, seasons, and entire lifetimes.

Location 2. Café de Flore

Stories to Navigate Our Way Through Life

Telling ourselves stories helps us navigate our way through life because they provide structure and direction. We are actually wired to tell stories. The human brain has evolved into a narrative-creating machine that takes whatever it encounters, no matter how apparently random and imposes on it ‘chronology and cause – and – effect logic’. We automatically and often unconsciously, look for an explanation of why things happen to us and ‘stuff just happens’ is no explanation.

Stories impose meaning on the chaos; they organize and give context to our sensory experiences, which otherwise might seem like no more than a fairly colorless sequence of facts. Facts are meaningless until you create a story arond them.

Stories to Navigate Our Way Through Life: Café de Flore (2-Minute Walk from Hotel Lutetia)

Just a quick 2-minute walk from Hotel Lutetia along the bustling Boulevard Saint-Germain lies Café de Flore, one of Paris’s most storied Left Bank haunts. This isn’t merely a charming spot for espresso and people-watching; it’s a living testament to how humans transform life’s raw chaos into navigable narratives. From its green awning and wicker chairs, generations of thinkers have stared into the void of uncertainty and emerged with stories that imposed order, meaning, and direction. For your Hero’s Journey leadership walking tour, “The Power of Your Story,” this location perfectly embodies the text’s core idea: we are wired to create stories because facts alone are inert—colorless sequences without chronology, cause-and-effect, or purpose—until we weave them into tales that guide us forward.

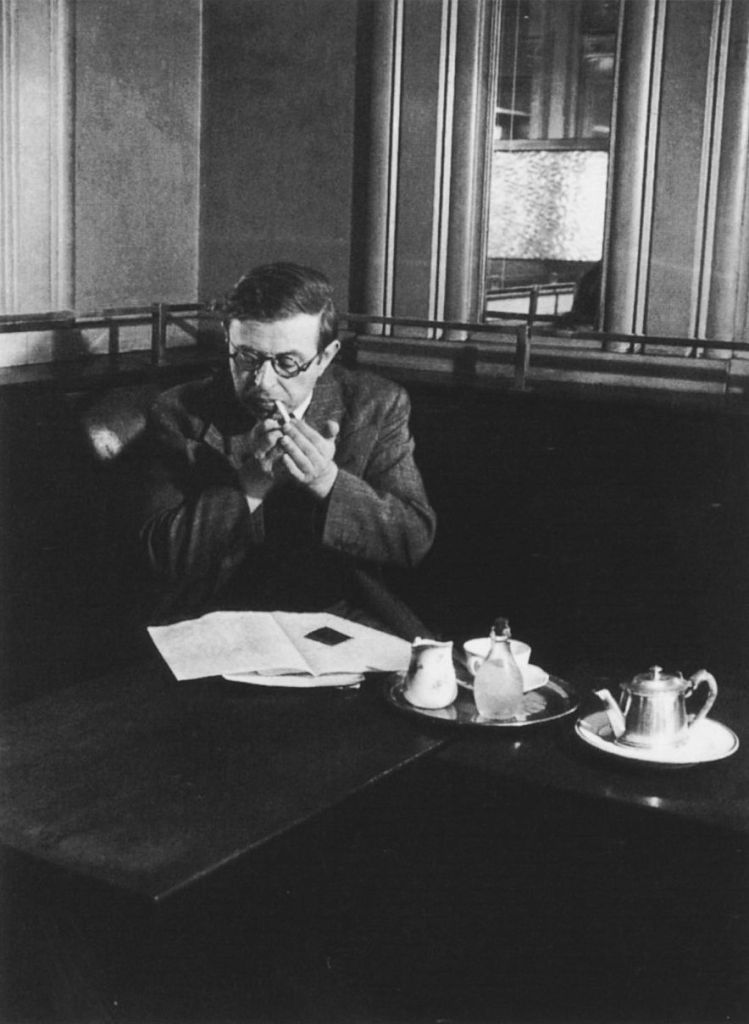

Café de Flore opened in 1887, but its golden era as a storytelling laboratory unfolded in the 1930s and 1940s amid Paris’s darkest hours. Jean-Paul Sartre claimed a permanent table here, arriving daily around noon for marathon sessions fueled by coffee, cigarettes, and endless scribbling. Simone de Beauvoir, his lifelong partner and collaborator, often joined him, as did Albert Camus, Pablo Picasso, and other luminaries escaping the German occupation’s grim reality. Outside, Nazi officers patrolled; ration cards dictated meals; air raid sirens pierced the night. Inside Flore, amid clinking cups and heated debates, these intellectuals didn’t surrender to randomness. They dissected existence itself, forging philosophies from fragments.

Sartre’s masterpiece Being and Nothingness (1943) was born here. Picture the scene: a blackout dims the boulevard, a friend vanishes into the Resistance, lovers argue over betrayal. These were stark facts—”stuff just happens.” But Sartre’s brain, like ours, craved narrative. He imposed structure: Existence precedes essence. Humans aren’t born with fixed purpose; we create it through choices amid absurdity. His stories weren’t escapist fairy tales; they were survival tools, turning sensory chaos (hunger pangs, whispered fears, fleeting freedoms) into a roadmap for authenticity. De Beauvoir extended this in The Second Sex, narrating women’s subjugation not as random oppression but as a plot arc demanding rebellion. Camus, sipping nearby, penned The Myth of Sisyphus, reframing eternal boulder-pushing as heroic defiance. Flore became their neural narrative machine, proving your point: the human brain evolved to storify everything, rejecting meaninglessness.

Location 3. Les Deux Magots

What Do I Mean with Story?

By ‘story’ I mean those tales we create and tell ourselves and others, and which form the only reality we will ever know in this life. Our stories may or may not conform to the real world. They may or may not inspire us to take hope – filled action to better our lives. They may or may not take us where we ultimately want to go. But since our destiny follows our stories, it is imperative that we do everything in our power to get our stories right.

For most of us, that means some serious editing.

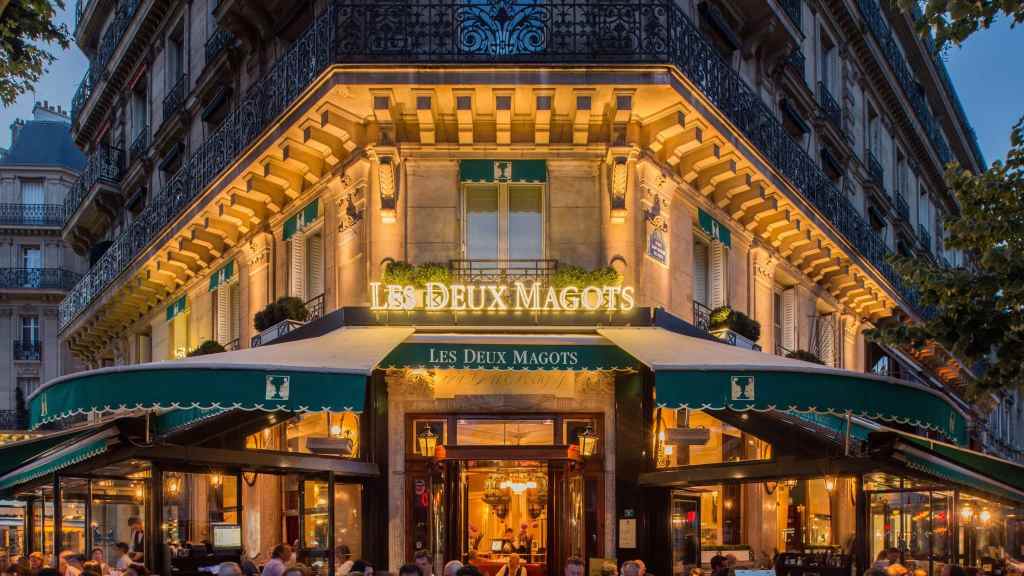

Stories Form Our Only Reality: Les Deux Magots (1-Minute Walk from Café de Flore)

A mere 1-minute walk from Café de Flore—cross Boulevard Saint-Germain to Place Saint-Germain-des-Prés—stands Les Deux Magots, Paris’s other existentialist landmark. This café, with its twin magots (Chinese sage statues) guarding the terrace, isn’t just Flore’s rival; it’s a shrine to how stories we tell ourselves become our destiny, demanding ruthless editing for hope-filled action. Opened in 1885, it drew Hemingway, Sartre, de Beauvoir, Camus, Picasso—and later, Julia Child—who didn’t just sip coffee; they edited life’s raw drafts into realities that propelled them forward. For your Hero’s Journey walking tour, “The Power of Your Story,” this spot illustrates perfectly: our tales may distort facts, but since destiny trails them, “getting our stories right” is leadership’s core edit.

Les Deux Magots peaked as a narrative workshop in the interwar and occupation years. Ernest Hemingway, broke and ambitious in the 1920s, claimed a terrace table, nursing one café au lait for hours while slashing his manuscripts. His early story “The Three-Day Blow” captures it: wind-whipped streets, inner turmoil, a boxing match as metaphor for resilience. Facts were brutal—WWI scars, poverty, F. Scott Fitzgerald’s shadow. His initial story? “I’m a failed vet turned hack; this city chews dreamers.” That tale led nowhere. So he edited: “War broke me, but Paris rebuilds heroes through discipline and truth.” This new reality fueled The Sun Also Rises, launching his legend. Sartre and de Beauvoir edited here too, turning occupation dread into No Exit‘s “Hell is other people”—not defeatist whine, but call to authentic choice. Camus reframed plague as absurd revolt. Picasso sketched amid debates, editing Cubism from fragmented life into destiny-shaping visions.

Enter Julia Child, whose Magots visits in the 1940s-50s add a triumphant layer. A lanky 6’2″ American newlywed in post-war Paris, she arrived at Le Cordon Bleu feeling like an awkward outsider: “Tall Yankee klutz can’t boil water.” Facts: Failed soufflés, snobby French chefs, language barriers. Her unedited story? “I’m a diplomat’s wife playing house; cooking’s for pros, not me.” Destiny: Stay sidelined. But at Magots’ terrace—spotting locals savoring simple omelets—she edited ruthlessly: “My height’s an asset for chopping; flops are data; Paris demands I master joie de vivre.” This tale birthed Mastering the Art of French Cooking (1961), The French Chef TV show, and a culinary revolution. Child didn’t conform to “reality”; she rewrote it, turning flops into “bon appétit!” empire. Her story-edit proves your text: even distorted tales, if inspiring, lead to wanted destinies.

To edit a dysfunctional story, you must first identify it. To do that you must answer the question: In which important areas of my life is it clear that I cannot achieve my goals with the story I have got? Only after confronting and satisfactorily answering this question can you expect to build new reality – based stories that will take you where you want to go.

Is this all starting to sound a little vague? I’m not surprised. But hold on. I understand you may be thinking Life as a story? The whole concept strikes you, perhaps, as a tad …. soft. I don’t look at my life in terms of story, you say. I disagree. Your life is the most important story you will ever tell, and you are telling it right now, whether you know it or not. From very early on you are spinning and telling multiple stories about your life, publicly and privately, stories that have a theme, a tone, a premise – whether you know it or not. Some stories are for better, some for worse. No one lacks material. Everyone’s got a story.

And thank goodness. Because our capacity to tell stories is, I believe, just about our profoundest gift. Perhaps the true power of the story metaphor is best captured by this seemingly contradiction: we employ the word ‘story’ to suggest both the wildest of dreams (it is just a story ……) and an unvarnished depiction of reality (okay, what is the story?). How is that for range?

The challenge? Most of us are not writers. ‘I am not a professional novelist’ one client said to me, when finally the time came for him to put pen to paper. ‘If this is the story of my life, you are damn right I’m intimidated. Can you give me a little help in how to get this out? That’s what I intend to do with the Hero’s Journey and The Heroine’s Journey project. First, help you to identify how pervasive the story is in life, your life, and second, to rewrite it.

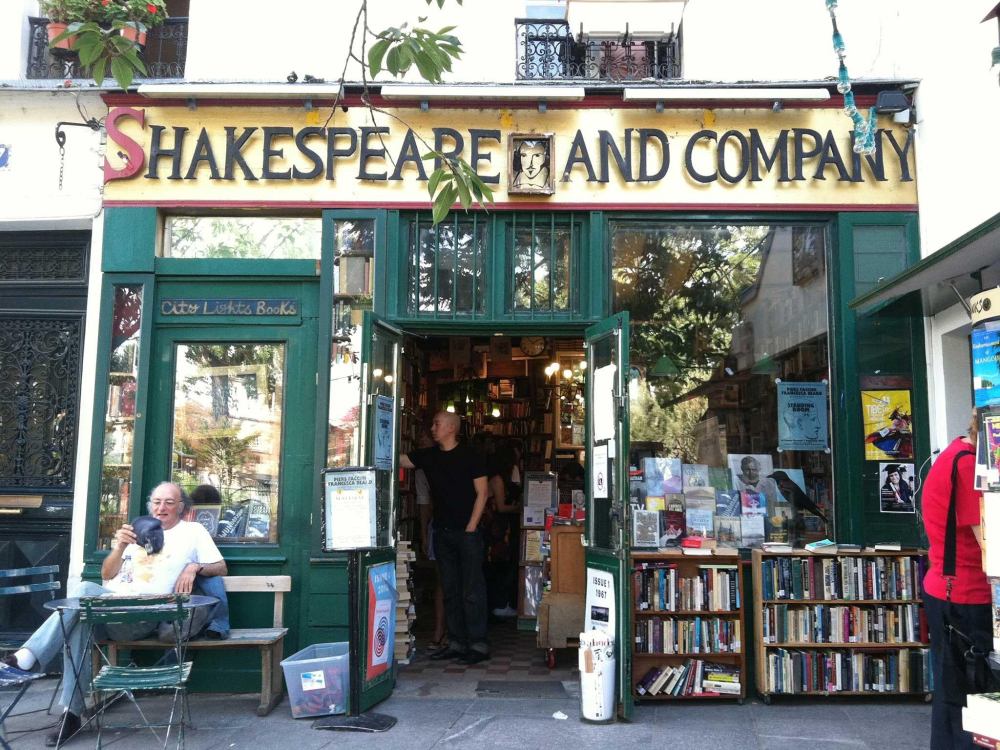

From Les Deux Magots to Shakespeare & Company: Walking the Path of Rewritten Stories

Imagine this: you’re sipping espresso at Les Deux Magots, where Sartre wrestled with life’s absurdity just meters away. The text’s challenge rings in your ears: “To edit a dysfunctional story, you must first identify it. In which important areas of my life can I not achieve my goals with the story I have?” You step outside, cross Boulevard Saint-Germain, and in 2.5 minutes—past the existential café buzz—you stand before Shakespeare & Company (37 Rue de la Bûcherie). Here, George Whitman’s life became the answer.

Whitman arrived in Paris in 1951, a drifter carrying his own broken narrative. Post-WWII Europe offered no clear path; his story whispered failure across every key domain: no creative legacy, no financial security, no lasting impact. Like so many, he told himself, “This is just how life goes—wandering, waiting.” Sound familiar? The text nails it: we all spin these stories from childhood, some elevating, most imprisoning. Whitman’s felt like the latter—a tale of aimless potential, vivid enough to hurt but too vague to change.

Then came the confrontation. Standing where Sylvia Beach’s original Shakespeare & Co once stood (the shop that published Joyce’s Ulysses), Whitman faced the text’s pivotal question head-on. His life areas screamed dysfunction: intellectual ambition stalled, relationships transient, purpose absent. “I cannot achieve my goals with this story,” he realized. No more waiting for destiny. No more “someday I’ll write/find meaning.” The drifter story died that moment.

What followed was pure rewriting magic. Whitman didn’t just dream—he built. He opened Shakespeare & Company as a living writer’s utopia, stamping every book with “rag and bone shop of the heart.” He offered free beds to struggling authors (over 30,000 housed, from Ginsberg to young unknowns). His new premise? “I create spaces where stories become reality.” What began as the “wildest of dreams” (a broke American funding literary haven) transformed into unvarnished reality: decades of near-bankruptcy, yet launching generations of writers. Hemingway, Miller, and countless others passed through his creaky stairs and overflowing shelves.

This is the text’s paradox captured in bricks and mortar: we use “story” for both fairy tales (“it’s just a story”) and hard truth (“what’s the story?”). Whitman’s bookstore embodies both—the utopian dream of literary fellowship meeting the gritty reality of bounced checks and endless hustle. And like Peter’s Hero’s Journey promise, Whitman helped non-writers tell their tales. “I’m not a professional novelist,” his guests confessed. He handed them the stamp, the bed, the connection—a toolkit to externalize inner narratives.

The walk itself mirrors the arc: Les Deux Magots (Sartre identifying existential dysfunction) → Pont au Double (the confrontation crossing the Seine) → Shakespeare & Co (rewritten reality standing firm). Just 300 meters, but it traces the text’s wisdom: only after facing your story’s failures can you author the one that “takes you where you want to go.”

Today, Whitman’s legacy thrives. Visitors still climb his perilous spiral staircase, sleep in designated beds, join the “Tumbleweed” network of global writers. His daughter Sylvia carries the story forward. Above the door: “Everyone’s got a story.”

Stand where Whitman stood. Feel the weight of authored lives. From café philosophy to bookstore reality, this 2-minute walk proves: your life is the most important story you’ll ever tell—and you’re telling it right now.

Every life has elements to it that every story has – beginning, middle, and end; theme; subplots; trajectory; tone.

Story is everywhere in life. Perhaps your story is that you are responsible for the happiness and livelihoods of dozens of people around you and you are the unappreciated hero. If you see things in more general terms, maybe your story is that the world is full of traps and misfortune – at least for you – and you’re the perpetual victim (I’m always so unlucky…. I always end up getting the short end of the stick…. People can’t be trusted and will take advantage of me if I give them the chance.).

If you are focused on one subplot – business say – then maybe your story is that you sincerely want to execute the major initiatives in your company, yet you are restricted in some essential way and thus can never get far enough from the forest to see the trees. Maybe your story is that you must keep chasing even though you already seem to have a lot (even too much) because the point is to get more and more of it – money, prestige, power, control, attention. Maybe your story is that you and your children just can’t connect. Or your story might be essentially a rejection of another story – and everything you do is filtered through that rejection.

Stories are everywhere. Your body tells a story. The smile or frown on your face, your shoulders thrust back in confidence or slumped roundly in despair, the liveliness or fatigue in your gait, the sparkle of hope and joy in your eyes or the blank stare, your fitness, the size of your gut, the tone and strength of your physical being, your overall presentation – those are all part of your story, one that’s especially apparent to everyone else. We judge books by their covers not simply because we are wired to judge quickly but because the cover so often provides astonishing accurate clues to what is going on inside. What is your story about your physical self? Does it truly work for you? Can it take you where you want to go in the short term? How about ten years from now? What about thirty?

Victor Hugo’s The Hunchback of Notre-Dame: A Masterclass in Life’s Hidden Story Arcs

Victor Hugo’s 1831 masterpiece masquerades as a gothic romance but reveals itself as a ferocious anatomy of human narrative—every element of story pulsing through Quasimodo’s deformed frame and Notre-Dame’s crumbling stone. This is no sentimental tale of beauty and the beast. It’s a mirror held to every reader’s physical and existential reality, demanding we confront the premises broadcasting from our shoulders, eyes, and gaits before we utter a word.

Quasimodo doesn’t walk—he lurches. His bell-rhythm gait marks him as outsider before his scarred face repels. Shoulders thrust forward hide his deformity, eyes—one blind, one desperate—betray hope battling rejection. His body screams “My ugliness dooms me to isolation” louder than any dialogue. Hugo understood the text’s wisdom perfectly: “Your body tells a story… we judge books by covers because they provide accurate clues to what is going on inside.” Quasimodo’s physical premise imprisons him more surely than Notre-Dame’s tower.

The novel’s true genius lies in its competing premises colliding. Archdeacon Frollo preaches “Religious duty justifies my lust”, Phoebus the captain embodies “Charm conquers all”, Esmeralda dances “Freedom beyond Paris’ cruelty”, while Quasimodo whispers “If I save her, I prove my worth”. These storylines don’t politely coexist—they explode in the tragic middle, bending every trajectory toward catastrophe. Hugo shows how subplots consume bandwidth, blinding us to our larger narrative.

Every story element lives vividly:

- Theme: “Unappreciated outsiders desperately seek belonging”

- Beginning: Abandoned infant → tower prisoner

- Middle: Love for Esmeralda → frantic protector swinging from cathedral heights

- End: Starves embracing her corpse, final premise “Monsters love truly, but society destroys what it fears”

- Tone: Tragic grandeur—wild acceptance dreams crash against brutal physical reality

Most crucially, Hugo makes the cathedral the true protagonist. Published when Notre-Dame faced demolition, the novel exploded tourism, raised restoration funds, saved the gothic giant. Quasimodo becomes subplot; stone claims hero status. The physical transformation mirrors the inner rewrite: sagging flying buttresses thrust confidently skyward, gargoyles regain defiant sneer, rose windows blaze like restored hope.

Readers confront their own physical stories. Quasimodo’s slumped shoulders mirror our stress-hunched spines. His desperate eye echoes our darting rejections. His muscular-yet-trapped frame warns of our own wasted potential. Hugo demands: “Does your gait signal destination or drift? Do your eyes promise connection or isolation? Can your physical trajectory sustain thirty years?”

The novel’s shadow lingers in restored Notre-Dame’s 2026 spires. Hugo proved bodies broadcast truth before words—Quasimodo’s hunch told his tragedy before Esmeralda appeared. Your shoulders write Chapter 1 before you speak Chapter 2. From tower prisoner to posthumous savior (his love purified in death), Quasimodo reveals every life’s complete arc hiding in plain sight.

The 400 Blows

François Truffaut’s The 400 Blows is a landmark of French cinema that beautifully illustrates the philosophical idea that our lives are the stories we tell ourselves, consciously and unconsciously—a theme that echoes in the text provided.

The film centers on Antoine Doinel, a Parisian adolescent navigating a world defined by unstable family relations, punitive educators, and the looming judgment of society. His experiences are episodic rather than strictly linear, presenting life as a sequence of moments—some apparently random, some deeply formative—that together demand narrative interpretation both from Antoine and the audience. Through his journey, the film reflects the fundamental drive to impose meaning on chaos: Antoine’s actions, whether mischievous or desperate, are attempts to craft a sense of identity and agency amid neglect and misunderstanding.

A crucial example occurs when Antoine, caught skipping school, concocts an elaborate lie that his mother has died—an impulsive story that snowballs and dictates his fate for much of the film. Here, storytelling becomes a survival tool and a means of self-definition: Antoine’s narrative, whether accurate or not, exerts real power over his present and future. In showing us his lies, hopes, and disappointments, Truffaut reveals that these “tales we create and tell ourselves and others… form the only reality we will ever know in this life,” as the quoted text suggests. Whether comforting or damaging, the stories Antoine tells (and believes) guide his choices and shape his destiny.

The 400 Blows is masterful in that it doesn’t offer a tidy, resolved story—it “starts where you arrive” and invites the viewer into Antoine’s world without insisting on artificial structure. The film’s celebrated final sequence, with Antoine escaping to the sea and turning to face the camera, is a powerful, open-ended image: a boy still editing the story of who he is and what his life means. This ambiguity reflects the relentless, unfinished process by which we construct and reconstruct our own narratives throughout our lives.

Truffaut’s compassionate realism, his refusal to moralize or sentimentalize Antoine’s fate, allows for a richly layered meditation on the power—and risk—of self-authored stories. By depicting a character whose “destiny follows his story,” The 400 Blows asks viewers to consider not only the stories we inhabit, but the responsibility we have to revise and “get our stories right” in order to seek hope, agency, and growth.

In summary, The 400 Blows stands as one of the most compelling cinematic explorations of the idea that “your life is your story, and your story is your life,” embodying the creative, often chaotic, but always essential act of making meaning from our experiences.

A great French movie that illustrates the concept of “Stories to Navigate Our Way Through Life” is Jean-Pierre Jeunet’s “Le Fabuleux Destin d’Amélie Poulain” (2001), commonly known simply as “Amélie.”

This film beautifully captures how humans are wired to create stories to give structure and meaning to life. Amélie, a shy and imaginative young woman living in Paris, crafts a whimsical narrative around her own life and the lives of those around her, using her stories to navigate loneliness, connection, and personal transformation.

The film’s narrative revolves around Amélie’s decision to intervene in the lives of strangers in small but profound ways, imagining the stories behind their actions and circumstances. She creates meaning and direction out of everyday facts—an unseen photograph, a lost treasure box, a lonely waiter—and her stories drive her to actions that bring joy and new connections. The way Amélie connects disparate events into a meaningful whole perfectly exemplifies how our brains impose chronology, cause, and effect logic on seemingly random experiences.

Moreover, “Amélie”’s visual style and narrative voiceover underscore how stories transform sensory experiences from mere facts into emotionally rich journeys. The iconic scenes of Montmartre, the quirky soundtrack, and surreal touches help frame Amélie’s internal and external worlds, making us feel how stories give context and coherence to human experience.

In short, “Amélie” is an exemplary French film that illustrates how storytelling is fundamental to making sense of life, structuring our reality, and inspiring hope-filled navigation toward connection and happiness. It embodies the idea that facts alone lack meaning until woven into the stories we tell ourselves and others

Jean Cocteau’s Orphée

The 1950 French film “Orphée,” directed by Jean Cocteau, is an exemplary illustration for the concept of story as the tales we create, which shape our reality, destiny, and perception of life. The film intricately weaves myth with reality and symbolically explores how the narratives we live by profoundly influence our existence and creative expression.

At its core, “Orphée” retells the ancient Greek myth of Orpheus, a poet who journeys into the underworld to rescue his deceased wife, Eurydice, with the condition that he must never look upon her face if he wishes to bring her back to life. Cocteau adapts this myth into a modern Parisian setting, blending reality with the supernatural to create a liminal “zone”—a mythical, shadowy realm constructed from memories and ruins that acts as a metaphor for the poet’s internal creative and existential journey. This “zone” is an artistic space where reality, memory, death, and creativity intersect, embodying the idea that our stories are neither strictly real nor entirely fantastical but a hybrid of both, shaping the only reality we inhabit.

Cocteau himself described the film’s key themes as the successive deaths a poet undergoes before achieving immortality, the concept of immortality through sacrifice, and the symbolic power of mirrors as gateways between life and death, reality and unreality. Mirrors in the film serve as portals to this suspended state where death wanders the streets of Paris, and the afterlife takes on a very this-worldly character through ritual interrogations and negotiations. This evokes the idea that our stories—like reflections—show fragments of ourselves changed over time, and confronting these narratives is essential for transformation or redemption.

The story of Orphée in the film is not just a myth retelling but an allegory for the creative process and the necessity of editing our lives and stories to find meaning and hope. Orphée’s journey is fraught with personal flaws and mistakes; his interactions with other characters—like the mysterious Princess who symbolizes death and sacrifice—underscore the difficulty in getting our stories “right.” The Princess sacrifices herself, erasing even her memory to permit Orphée’s immortality as a poet, symbolizing the painful yet necessary sacrifices in the creative and existential process to transcend ordinary life and rewrite our destinies.

The film also explores the tension between artistic inspiration and domestic realities. Orphée struggles with his role as a poet and his personal life, including his relationship with Eurydice and the impending birth of their child. This dynamic illustrates how our life stories are continuously edited, shaped by choices, challenges, and sacrifices that often require balancing hope-filled action with acceptance of reality. Cocteau’s film suggests that destiny—our ultimate path—is not fixed but closely follows the stories we craft, revise, and live by, highlighting the imperative of actively shaping these stories to align with our deeper aspirations and truths.

Orphée’s tragic flaw—looking back on Eurydice—results in her disappearance and his own eventual death, leading him back to the underworld where love, sacrifice, and rebirth occur once more, emphasising the notion that stories are cyclical and require constant renewal. The film’s final resurrection and erasure of memory metaphorically propose that to live meaningfully, we must sometimes forget past failures and rewrite our narratives anew, reinforcing the idea that serious editing is vital in crafting the stories that will ultimately determine our destiny.

In summary, Jean Cocteau’s “Orphée” is a profound cinematic exploration of how the stories we tell ourselves and others shape the only reality we will ever know. It eloquently captures the idea that while our stories may not completely conform to the external world, they direct our destiny. The film’s fusion of myth, poetic imagery, and existential themes serves as a cinematic metaphor for how humans must continually edit and refine their inner narratives to find immortality in the artistic, spiritual, or personal sense. “Orphée” teaches us that understanding and owning our stories, with all their flaws and sacrifices, is imperative to live authentically and with hope for a meaningful life and destiny.