The Hero’s Journey in Paris is a transformative five-day journey through the City of Light with Peter de Kuster, dedicated to teaching skills overlooked by traditional education—skills that build creative confidence and empower you to monetize your passion as a creative professional or coach. By wandering Paris’s iconic streets, cafés, and cinematic haunts tied to stories of creative heroes and heroines who walked before you, you’ll confront the deepest questions of your creative life and craft a bold, authentic narrative for career and impact. Blending storytelling, exercises, and intimate discussions, this Hero’s Journey equips participants with tools to guide clients (or yourself) toward fulfilling, profitable paths.

Practical Info

Pricing Options (per person, excluding VAT):

- Private 1:1 Intensive: €4,950 – Fully customized for solo creative pros or coaches seeking deep personal rewiring.

- Intimate Duo/Trio (2-3 participants): €3,250 – Ideal for coach-client pairs or small creative circles.

- Small Group Travel (4-8 participants): €695 – Group synergy, shared insights, and travel logistics included.

- Team/Practice Builder (9+ participants): €2,450 – Tailored for coaching practices or creative teams; contact for custom quotes.

Special discounts for groups of 3+ from coaching networks or creative collectives.

Book by emailing peterdekuster2023@gmail.com for dates, customization, or questions.

TIMETABLE

09:40 – Tea & Coffee on arrival (Left Bank café)

10:00 – Morning Session (storytelling walk + exercises)

13:00 – Lunch Break (bistro with reflection)

14:00 – Afternoon Session (deep dives at hero sites)

17:00 – Drinks (networking debrief)

Read on for a detailed breakdown of the Hero’s Journey itinerary in Paris.

The Hero’s Journey in Paris: Make Money Doing What You Love

Participants: even unconventional paths demand sustainable success. Peter de Kuster leads you through Paris—past Hemingway’s haunts, Sartre’s cafés, and Amélie’s Montmartre—with tales of past creatives who turned right-brain genius into empires. Tackle challenges like:

- Choosing careers aligning talents with income.

- Setting intuitive goals via story-mapping.

- Dodging traps that derail creatives (procrastination, underpricing).

- Networking as authentic “schmoozing.”

- Crafting personal business plans.

- Self-discipline as your own CEO.

Embrace acting, writing, coaching, or design with financial freedom—Peter reveals the hero’s toolkit.

Self-Promotion for Heroes

Struggling to shout your brilliance without burnout? In Paris’s galleries and boulevards, Peter unpacks Self-Promotion for Heroes: low-cost, creative hacks for participants to amplify visibility.

- Market with zero budget (storytelling leverage).

- Design self-selling assets (portfolios that pitch).

- Spark buzz via word-of-mouth rituals.

- Hack internet tools unconventionally.

- Win endorsements from industry leaders.

Self-promo isn’t sales—it’s claiming your narrative amid Chanel’s legacy and Picasso’s haunts.

The Financial Freedom to Create

Participants know: passion flows, but cash doesn’t always follow. Peter’s Financial Freedom to Create—explored at Dior’s haunts and entrepreneurial brasseries—delivers:

- Identifying top-marketable talents.

- Pricing like a pro (ditch “free freelance”).

- Debt traps in lean times, savings in booms.

- Funding dreams without soul-selling.

Real anecdotes from Peter’s 20+ years turn money into your creative ally.

Time for Heroes

Muses ignore deadlines—right-brainers need nonlinear mastery. At Shakespeare’s & Co. and Flore, Time for Heroes adapts time to you:

- Masterful “no” for overload.

- “Good enough” for progress.

- Fun-infused to-do lists.

- Home hacks freeing creative hours.

- Clutter control for flow states.

Turn Paris’s rhythm into your ally.

Practical Information

Core Ticket: €695 excl. VAT (small group travel). See tiers above.

Reserve: peterdekuster2023@gmail.com. Lodging, meals extra (recommend Left Bank for immersion).

About Peter de Kuster

Founder of The Hero’s Journey project, Peter helps participants build lives from core stories (values, traits, skills). With MBA in Marketing & Finance, Sociology/Communication degrees, and 20+ years, his books (Heroine’s/Hero’s Journey series) blend narrative and strategy for breakthroughs.

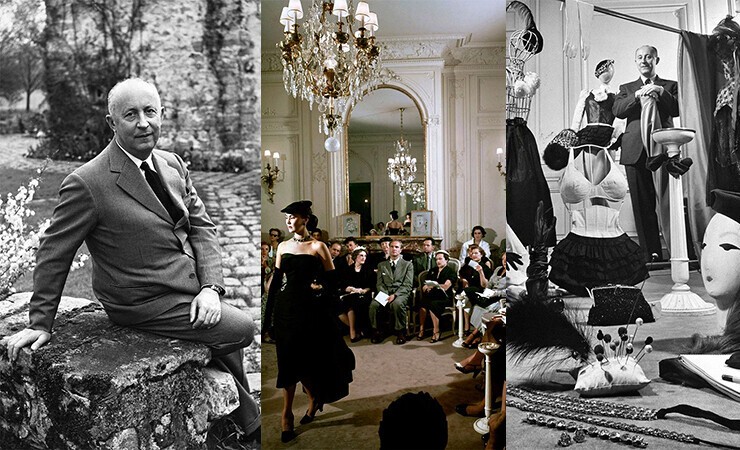

Christian Dior was born in 1905 in Granville, Normandy, into a comfortable bourgeois family—his father a wealthy fertilizer manufacturer, his mother dying young from tuberculosis, leaving him the eldest of five to navigate a strict Catholic upbringing. Yet even in relative stability, young Christian began telling himself a story of quiet rebellion: I am not the dutiful son bound to chemicals and convention; I am the dreamer who sees beauty in sketches and silhouettes. That inner narrative—of sensitivity amid rigidity, of art over inheritance—led him from political science studies (abandoned for the bohemian life) to selling charcoal fashion illustrations on Paris streets in the 1920s, dreaming of a world beyond his father’s expectations.

The 1929 crash shattered the family fortune, forcing Dior into odd jobs—ghost-designing for society ladies, illustrating Le Figaro—while he whispered to himself, Failure is not my end; it is the sketch before the masterpiece. By 1938, hired by Robert Piguet, then Lucien Lelong during WWII, he dressed Nazi officers’ wives and French Resistance figures alike, honing a wartime aesthetic of restraint amid rationing. His story evolved: In scarcity, I see abundance; in uniforms, I imagine femininity reborn. Post-liberation in 1946, textile magnate Marcel Boussac offered him a dying house; Dior refused, demanding his own: I will not revive the old; I will author the new. Backed by Boussac’s millions, he founded the House of Dior at 30 Avenue Montaigne, with 85 staff, vowing total creative control.

On February 12, 1947, his “New Look” debuted—nipped waists, padded hips, full skirts cinched with corsets, 20 yards of fabric per gown—scandalizing a war-weary world still in short hems and square shoulders. Dior’s inner script roared: I reject the poverty of rationing; I drape women in joy, in excess, in the femininity they starved for. Carmel Snow of Harper’s Bazaar gasped, “It’s quite a revolution, dear Christian,” and the world followed: Dior employed 2,000 by 1950, exported to five continents, spawning copycats from Tokyo to New York. He told himself, I am the liberator of silhouettes, turning postwar gray into golden curves. Yet privately, in his green-marble bathtub, sketching amid bubbles, he confided to friends his fear: What if they tire of my hourglass?

Expansion was relentless. In 1947, Miss Dior perfume launched, inspired by his Resistance-hero sister Catherine, tortured at Ravensbrück—sampling 10 scents, picking the fifth (his lucky number). Shoes with Roger Vivier (1953), lipstick, furs, ties followed, as licensing deals flooded America. Dior’s narrative swelled: I am not just a couturier; I am an empire of elegance. But cracks showed—health fragile from overwork, superstitions (lucky shamrocks pinned inside suits), a closeted homosexuality in judgmental times. He dressed royalty (Princess Margaret), stars (Marlene Dietrich), yet mourned his mother’s early death, weaving loss into opulence: From absence, I create presence.

By 1957, at 52, a heart attack felled him in Italy—rumors swirled of overeating, but his story ended mid-sentence: I have dressed the world; now it wears me. Yves Saint Laurent, his 21-year-old protégé, succeeded him, but the house endured under LVMH, its New Look a pivot from austerity to allure. Dior’s life proves the power of self-authored narrative: born privileged yet constrained, he rejected inheritance for invention, scripting scarcity into splendor. Like his cinched waists flaring to fullness, Christian Dior turned personal restraint into global revolution—the story he told himself about himself, from fragile boy to fashion king, draping history in his vision.

Philippe Starck was born in 1949 in Paris into a family of engineering and invention—his father an aeronautical creator who designed aircraft propellers, instilling in young Philippe a story of practical magic: I am not just a maker of objects; I am the inventor who fuses function with fantasy. That inner narrative—of rebellion against the ordinary, of everyday items reborn as art—led him from the École Camondo design school to crafting radical furniture in the 1970s, dreaming of a world where chairs whisper poetry and toothbrushes provoke thought.

The 1968 student uprisings electrified his youth, but economic realities forced Starck into nightclub design—Les Bains Douches, a pulsating Paris hotspot—while he told himself, Chaos is my canvas; nightlife is the laboratory for democratized design. By 1982, François Mitterrand appointed him “Officier des Arts et des Lettres” at age 33, the youngest ever, launching his global ascent. His breakthrough came with the Étoile de Vienne chair for XO, followed by the Dr Sonderbar juicer (1983)—a grinning plastic citrus squeezer that sold millions, proving his mantra: Ugly tools deserve ugly faces; beauty hides in whimsy. Whispering to himself, I turn the mundane into manifesto, he partnered with Kartell, Alessi, and Flos, scripting scarcity of imagination into abundance.

In 1984, Starck redesigned Paris’s Café Costes—plush velvet, starlit ceilings, a sensual haven—then the Royalton Hotel in New York (1988), birthing “design hotels” with Philippe Plechac lobby swagger. His inner script roared: I reject sterile spaces; I drape rooms in seduction and surprise. The lemon squeezer became iconic, but so did the Ghost Chair (2002, transparent polycarbonate), the Bubble Club sofa, and the Prince Albert teapot—playful yet precise. Private commissions followed: yachts for Roman Abramovich, private jets for Steve Jobs (the black-and-white iPod-inspired interior), the French presidential plane. He told himself, I am the people’s poet of plastic, dressing elites while arming the masses. Yet privately, sketching at dawn, he fretted: Will they see past the gimmick to genius?

Expansion was audacious. Starck launched Starckeyes sunglasses, Bonk compression socks (with compression for “lazy blood”), even coffins (“Democratic Death”). His Good Design for All manifesto birthed affordable lines: the Apollo toothbrush for Kartell, the Spoutnik kettle. Collaborations spanned Vitra chairs, Flos lamps (Tite LED, 2014), and hotels like the Flamingo Las Vegas redesign (neon tamed into chic). Starck’s narrative swelled: I am not a designer; I am a citizen-architect of joy. Cracks emerged—health strained by 500+ annual projects, a vegetarian eco-warrior railing against consumerism (“Design must be useful, durable, economic”), his private life shielded (five children across relationships). He dressed presidents (Mitterrand’s Elysee interiors), stars (Salma Hayek’s rose), yet mourned lost simplicity: From prototypes, I conjure poetry.

By his 70s, Starck—still wiry, bespectacled, philosophizing—launched Pleyel pianos, electric bikes, even a low-cost house (Seedhouse, solar-powered). Rumors of burnout swirled, but his story endures unfinished: I have squeezed the world’s lemons; now it juices me. Successors like Eugeni Quitllet carry his torch at Kartell, but the Starck empire thrives under his vision. Starck’s life proves self-authored narrative’s power: born to engineers yet unbound, he rejected utility for utopia, scripting plastic into poetry. Like his Dr Sonderbar’s eternal grin, Philippe Starck turned functional frustration into global glee—the story he told himself about himself, from propeller kid to design democrat, squeezing history’s juice into whimsy.

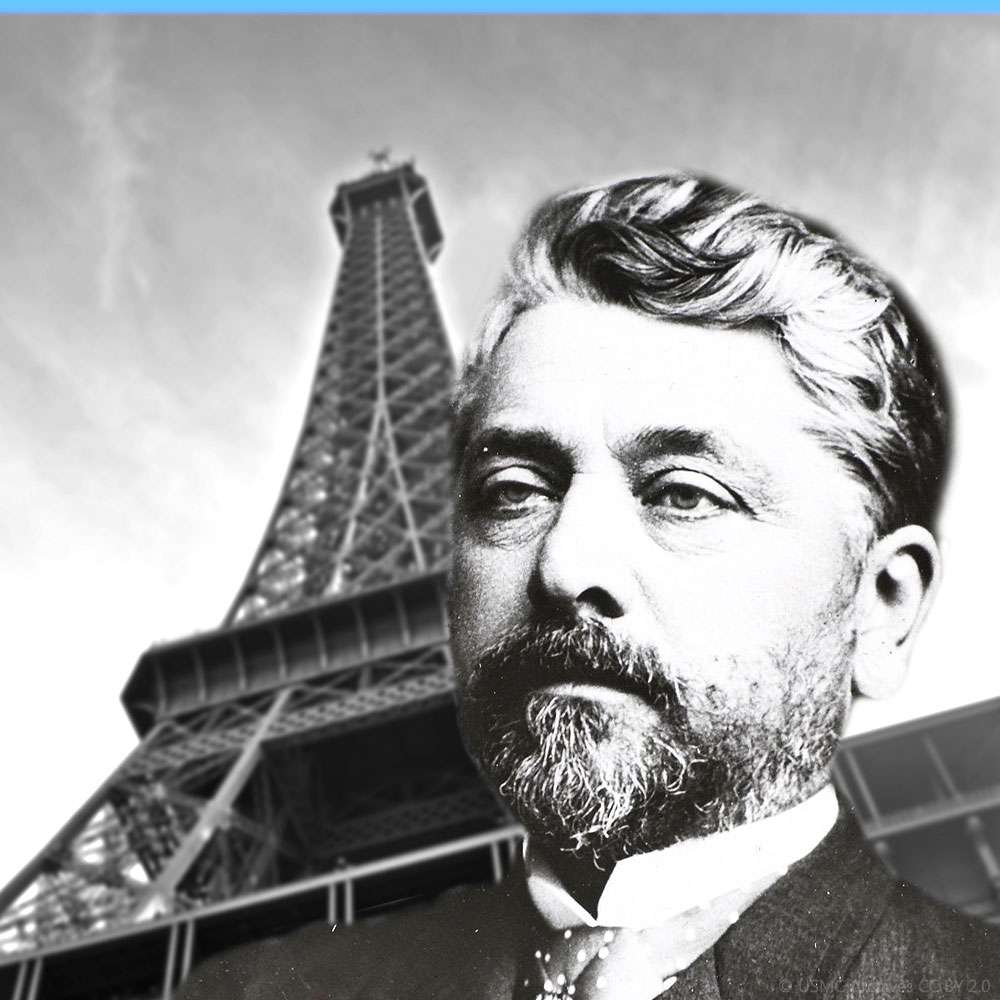

Gustave Eiffel was born in 1832 in Dijon, France, into a modest family of salt merchants and winemakers—his father a veteran of Napoleon’s army, his mother running the family trade while raising him amid the humdrum predictability of provincial life. Even in this stable but stifling world, young Alexandre-Gustave began telling himself a story of upward defiance: I am not the merchant’s son destined for ledgers and casks; I am the builder who lifts iron into the sky. That inner narrative—of precision engineering as poetry, of structure as soaring ambition—led him from the École Centrale des Arts et Manufactures in 1855 to apprenticeships in bridges and factories, dreaming of a world where metal sang symphonies against gravity.

The 1850s industrial boom tested his mettle; Eiffel designed his first bridge in 1860 near Bordeaux, whispering to himself, Failure bends but does not break; each rivet is a verse in progress. By the 1870s, he pioneered prefabricated ironwork, erecting viaducts across Portugal and the Douro River—structures that withstood floods and quakes—while honing a wartime ethos during the Franco-Prussian siege: In chaos, I forge order; in invasion, I erect endurance. His story evolved: Scarcity of stone yields abundance of steel; uniforms of war birth frameworks of peace. In 1876, the colossal Garabit Viaduct—540 meters long, 122-meter arch—proved his mastery, a “viaduct cathedral” that awed engineers worldwide. He told himself, I am the skeleton-maker of landscapes, turning rivers into reverence.

By 1880s Paris, hosting the Universal Exposition, Eiffel won the tender for the Exposition Universelle centerpiece: a 300-meter iron tower, initially mocked as “Eiffel’s useless giraffe” by artists and writers (including Guy de Maupassant, who lunched there to avoid seeing it). His inner script thundered: I reject the scorn of aesthetics; I drape the horizon in audacity, proving height is humanity’s hymn. Opened March 31, 1889—for France’s centennial revolution—it drew 2 million visitors, funding his labs and silencing critics. Wind-tested to 200 km/h, lit by electric arcs (first in Europe), it stood as the world’s tallest until 1930. Privately, amid blueprints and calculations, he confided fears: What if the wind topples my dream? Yet crowds ascended, gasping at Seine vistas, validating his mantra.

Expansion was visionary. Eiffel’s designs spanned continents: the São Paulo dos Campos viaduct (Brazil, 1884), Statue of Liberty’s internal pylon (1887, collaborating with Bartholdi—”I give her bones”), locks for Panama Canal (abandoned amid scandal, but his equatorial frame aided telescope foundations). Trains, greenhouses, markets followed—over 700 structures. His narrative swelled: I am not mere constructor; I am citizen-engineer of progress. Cracks appeared—bankruptcy threats post-Exposition, 1893 Panama trial (acquitted, but reputation scarred), a closeted life amid Victorian mores. He aided humanity (1898 meteorograph for weather, 1913 wireless telegraphy tower), yet mourned lost simplicity: From rivets, I raise redemption.

By 1923, at 91, Eiffel died in his Paris home, honored by the Académie des Sciences—his tower enduring, now a global icon (65 million visitors yearly). Successors like his grandson built on his lattice, but Eiffel’s legacy thrives: UNESCO sites, engineering schools named for him. Eiffel’s life proves self-authored narrative’s power: born bourgeois yet earthbound, he rejected trade for transcendence, scripting iron into immortality. Like his tower’s elegant taper—strong at base, graceful at peak—Gustave Eiffel turned structural restraint into skyward revolution, the story he told himself about himself—from salt-boy to spire-lord—hoisting Paris into eternity.