Writing a new story.

A journey through Paris following the work of famous Paris artists

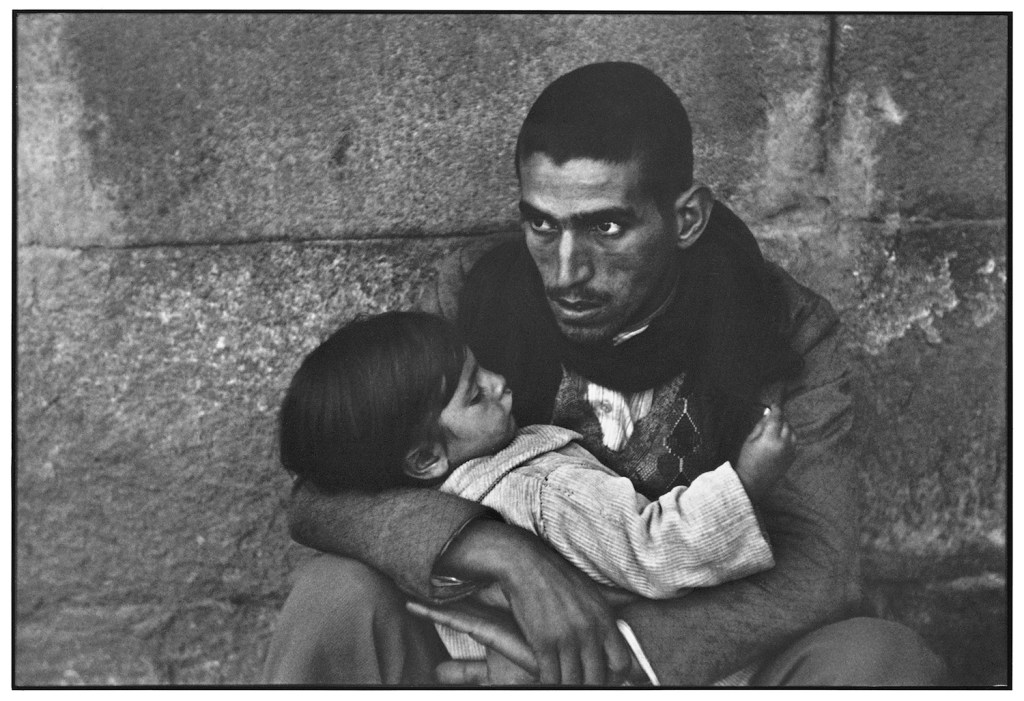

like Henry Cartier Bresson

A story about getting unwell.

About losing direction and hope, about imagining

that we have let ourselves and everyone down

But it is also a story about getting better.

About regaining the thread, rediscovering meaning

And finding a way back to connection and joy.

I follow the arc of a hero’s or heroine’s journey, from

challenge to freedom. The moment we realize we cannot

cope; the acts of self-care in which we find respite;

and the day we finally reclaim a sense of stability.

Written with understanding and kindness, it is both

a source of companionship in our loneliest moments –

whether we’re experiencing a relationship breakdown,

a career setback, a health crisis or anxiety around the

everyday – and a practical guide that will help us find

reason for hope.

We are all on our own hero’s or heroine’s journey towards

being more authentic. This story will help us along the way.

Join Peter for a truly transformational vacation for the mind.

About Peter de Kuster

Peter de Kuster is the founder of The Hero’s Journey & The Heroine’s Journey project, a storytelling firm which helps creative professionals to create careers and lives based on whatever story is most integral to their lives and careers (values, traits, skills and experiences). Peter’s approach combines in-depth storytelling and marketing expertise, and for over 20 years clients have found it effective with a wide range of creative business issues.

Peter is writer of the series The Heroine’s Journey and Hero’s Journey books, he has an MBA in Marketing, MBA in Financial Economics and graduated at university in Sociology and Communication Science

Practical Info

The price of this one day tour with Peter de Kuster is Euro 995 excluding VAT

You can reach Peter for questions about dates and the program by mailing him at peterdekuster@hotmail.nl

TIMETABLE

09.40 Tea & Coffee on arrival

10.00 Morning Session

13.00 Lunch Break

14.00 Afternoon Session

17.00 Drinks

Part I. The Challenge

If we are lucky, when it feels impossible to carry on any longer we will know to put up the white flag at once. There is nothing shameful or rare in our condition; we have fallen ill, as so many before us have. We need not compound our sickness with a sense of embarassment. This is what happens when one is a delicate human facing the hurtful, alarming and always uncertain conditions of existence. Recovery can start the moment we admit we no longer have a clue how to cope.

The roots of the crisis almost certainly go back a long way. Things will have not been right in certain areas for an age, possibly for ever. There will have been grave inadequacies in the early days, things that were said and done to us that should never have been, and bits of reassurance and care that were ominously missed out. In addition to this, adult life will have layered on difficulties which we were not well equipped to know how to endure. It will have applied pressure along our most tender, invisible fault lines.

Our breakdown is trying to draw attention to our problems, but it can only do so inarticularly, by throwing up coarse and vague symptoms. It knows how to signal that we are worried and sad, but it can’t tell us what about and why. That will be the work of patient investigation of your story. The breakdown contains the cure, but it has to be teased out and its original inarticulate story interpreted. Something from the past is crying out to be recognized and will not leave us alone until we have given it its due.

It may seem – at points – like a death sentence but we are, beneath the crisis, being giving an opportunity to restart our lives on a more generous, kind and realistic footing. There is an art to having a breakdown – and to daring at least listen to what our pain is trying to tell us.

Mental health is a miracle we are apt not to notice until the moment it slips from our grasp – at which point we may wonder how we ever managed to do anything as complicated and beautiful as order our story sanely and calmly.

A mind in a healthy state is, in the background, continually writing a near-miraculous set of stories that underpin our moods of clear-sightedness and purpose. To appreciate what a mental healthy story involves – and therefore what makes up its opposite – we should consider some of what will be happening in the folds from an optimally functioning inner storytelling mind:

- First and foremost, a healthy mind is an editing mind, an organ that manages to sieve, from thousands of stray, dramatic, disconcerting or horrifying stories, those particular ones and sensations that actively need to be entertained in order for us to direct our lives effectively.

- Partly this means keeping at bay punitive and critical judgements that might want to tell us repeatedly how disgraceful and appalling we are – long after harshness has ceased to serve any useful purpose. When we are taking someone one a date, a healthy inner storyteller doesn’t force us to listen to voices that insist on ourunworthiness. It allows us to talk to ourselves as we would to a friend.

- At the same time, a healthy inner storyteller resists the pull of unfair comparisons. It doensn’t constantly allow the achievements and successes of others to throw us off course and reduce us to a state of bitter inadequacy. It doesn’t torture us by continually comparing our condition to that of people who have, in reality, had very different upbringings and trajectories through life. A well-functioning storytelling mind recognizes the futility and cruelty of constantly finding fault with its own nature.

- Along the way, a healthy inner storyteller keeps a judicious grip on the drip, drip, drip of fear. It knows that, in theory, there is an endless number of things that we could worry about; a blood vessel might fail, a scandal might erupt, the plane’s engines could sheer from its wings… But it has a good sense of the distincition between what would conceivably happen and what it is in fact likely to happen, and so it is able to leave us in peace as regards the wilder eventualities of fate, confident that awful things will either not unfold or could be dealt with ably enough if ever they did so. A healthy inner storyteller avoids catastrophic imaginings; it knows that there are broad and stable scenes, not a steep and slippery slope, between itself and disaster.

- A healthy inner storyteller has compartments in their story with heavy doors that shut securely. It can compartmentalize when it needs to. Not all thoughts belong at all moments. While talking to a grand mother, the mind prevents the emergence of images of last night’s erotic fantasies; while looking after a child, it can repress its more cynical and misanthropic analyses. A healthy inner storyteller has mastered the techniques of censorship.

- A healthy inner storyteller can quieten its own buzzing preoccupations in order, at times, to focus on the world beyond itself. It can be present and engaged with what and who is immediately around. Not everything it could feel has to be felt at every moment.

- A healthy inner storyteller combines an appropriate suspicion of certain people with a fundamental trust in humanity. It can take an intelligent risk with a stranger. It doesn’t extrapolate from life’s worst moments in order to destroy the possibility of connection.

- A healthy inner storyteller knows how to hope; it identifies and then hangs on tenaciously for a few reasons to keep going. Grounds for despair, anger and sadness are, of course, all around. But the healthy mind knows how to bracket negativity in the name of endurance. It clings to evidence of what is still good and kind. It remembers to appreciate; it can – despite everything – still look forward to a hot bath, some dried fruit or a satisfying day of work. It refuses to let itself be silenced by all the many sensible arguments in favor of rage and despondency.

Outlining some of the features of a healthy inner storyteller helps us identify what can go awry when we fall ill. At the heart of mental illness is a loss of control over our own better thoughts and feelings. An unwell inner storyteller can’t apply a filter to the information that reaches our awareness; it can no longer order or sequence its content. And from this, any number of painful scenarios ensue:

- Ideas keep coming to the fore that serve no purpose, unkind voices echo ceaselessly. Worrying possibilities press on us all at once, without any bearing on the probability of their occurence. Fear runs riot.

- Simultaneously, regrets drown out any capacity to make our peace with who we are. Every bad thing we have ever said or done reverberates and cripples our self-esteem. We are unable to assign correct proportions to anything: a card that gets lost feels like a conclusive sign that we are doomed; a slightly unfriendly remark by a collague becomes proof that we shouldn’t exist. We can’t grade our worries and focus in on the few that might truly deserve concern.

- We can’t temper our sadness. We can’t overcome the idea that we have not been loved properly, that we have made a mess of the whole of our working lives, that we have disappointed everyone who ever had a shred of faith in us.

- Every compartment of the mind is blown open. The strangest, most extreme thoughts run unchecked across consciousness. We begin to contemplate extreme actions like taking on 6 morfine plasters and a bottle of cognac.

- In the worst cases, we lose the power to distinguish outer reality from our inner world. We can’t tell what is outside us and what inside, where we end and others begin; we speak to people as if they were actors in our own dreams.

- At night, such is the hefty storytelling and the ensuing exhaustion that we become defenceless before our worst apprehensions. By 3 hour clock in the night, after hours of rumination, doing away with ourselves no longer feels like such a remote or unwelcome notion.

However dreadful this inner storytelling sounds, it is a paradox that, for the most part, mental flawed storytelling doesn’t tend to look from the outside as dramatic as we think it should. The majority of us, when we have an internal flawed story, will not be foaming at the mouth or insisting that we are Napoleon. Our suffering will be quiteter, more inward, more concealed and more contiguous with societal normas; we’ll sob mutely into the pillow or dig our nails silently into our palms. Others may not even realize for a very long time, if ever, that we are in difficulty. We ourselves may not quite accept the scale of our sickness.

A flawed inner storyteller is ultimately as common, and as essentially unshameful, as its bodily counterpart – and also comprises a host of more minor ailments, the equivalents of cold sores and broken wrists, abdominal cramps or ingrowing toenails.

When we define a flawed inner storyteller as a loss of command over the mind, few of us can claim to be free of all instances of flawed inner storytelling. True healthy inner storytelling involves a frank acceptance of how much unhealthy storytelling there will have to be even in the most ostensibly competent and meaningful lives. There will be days when we simply can’t stop crying over someone we have lost. Or when we worry so much about the future that we wish life would end right now. Or when we feel so sad that it seems futile even to open our mouths. We should at such times be counted as no less ill than a person laid up in bed with flu – and as worthy of attention and sympathy.

It doesn’t help that we are at least a hundred years away from properly fathoming how the brain operates – and how it might be healed. We are in the mental arena roughly equivalent to where we might have been in bodily medicine around the middle of the seventeenth century, as we slowly built up a picture of how blood circulated around our veins or our kidneys functioned. In our attempts to find fixes we are akin to those surgeons depicted in early prints who cut up cadavers with rusty scissors and clusily dug around the innards with a poker. We will – surpisingly – be well on the way to colonizing Mars before we definitively grasp the secrets to the workings of our own minds.

This journey through Paris aims to be a sanctuary where we can sit once in a while and recover our strength, in an atmosphere of kindness and fellow feeling. It outlines a raft of storytelling moves with which we might approach our most stubborn unhealthy inner storytelling and instabilities. It sets out to be a friend through some of the most difficult moments of our lives.

Our societies sometimes struggle with the question of what stories in art, literature, film might be for. Here the answer feels simple: stories are a weapon against despair. They are tools with which to alleviate a sense of crushing isolation and uniqueness. It provides common ground where the sadness i n me can, with dignity and intelligence, meet the sadness in you.

Perhaps for a long tie, the man in the diner kept it together. As late as this morning, he might have believed that, despite everything he would be OK. He’d taken his hat along with him, as always he remained attached to appearances. Even as his anguish mounted, he kept going, one sip of coffee after another, an ocassional par of the mouth with a paper napkin, while looking at the busy room: secretaries at lunch, people from the nearby construction site, a few exhausted mothers and their kids. Then suddenly, there was no more arguing with the despair any longer. It swept him up without a chance of a rejoinder: the mess he had made, the fool he had become in everyone’s eyes, the absurdity of everything. His head hit the table with a shocking clatter but almost at once it was absorbed by the dense murmur of the room and the city. One could die in public here and few would notice.

Except that there was a French photographer right opposite who was very much into noticing everyting: an elegant, willowy man, with a name impossible for Americans to pronounce – he invited him to call him Harry – and a Leica 35 around his neck. Henri Cartier-Bresson had wandered the area all morning; he’s shot a group of women chatting outside on Ground Street and discovered a striking view of midtown Manhattan from the promenade. He had just begun his lunch, when, without warning, there came that distinctive bang of a heat hitting a table with force.

We need not feel ashamed, the photograph suggest, that we are in despair; it is an inevitable part of being alive. The distress that normally dwells painfully and privately inside our minds has been given social expression – and no longer needs to be shouldered alone. Whatever a distressingly upbeat world sometimes implies, it is normal, very normal, to be in agony. We don’t, on top of it all, ever need to feel unique for being unwell.

CURLING UP INTO A BALL

We cause ourselves a lot of pain by pretending to be competent, all-knowing, proficient adults long after we should,ideally, called for help. We suffer a bitter rejection in love, but tell ourselves and our acquaintances that we never cared. We hear some wounding rumours about us but refuse to stoop to our opponents’ level. We find we can’t sleep at night and are exhausted and anxious in the day, but continue to insist that stepping aside for a break is only for weaklings.

We all originally came from a very tight ball-like space. For the first nine months of our existence, we were curled up, with our head on our knees, protected from a more dangerous and colder world beyond by the position of our limbs.

In our young years, we knew well enough how to recover this ball position when things got tough. If we were mocked in the playground or misunderstood by a snappy parent, it was instinctive to go up to our room and adopt the ball position until matters started to feel more manageable again. Only later, around adolescence, did some of us lose sight of this valuable exercise in regression and thereby began missing out on a chance for nurture and recovery.

Dominant ideas of what can be expected of a wise, fully mature adult tend to lack realism. Though we may by twenty – eight or forty – seven on the outside, we are inevitably still carrying within us a child for whom a day at work will be untenably exhausting, a child who won’t be able to clam down easily after an insult, who will need reassurance after every minor rejection, who will want to cry without quite knowing why and who will fairly regularly require a chance to be ‘held’ until the sobs have subsided.

It is a sign of the supreme wisdom of small children that they have no shame or compunction about bursting into tears. They have a more accurate and less pride-filled sense of their place in the world than a typical adult: they know that they are extremely small beings in a hostile and unpredictable realm, that they can’t control much of what is happening around them, that their powers of understanding are limited and that there is a great deal to feel distressed, melancholy and confused about.

As we age, we learn to avoid being, at all cost, that most apparently repugnant – and yet in fact deeply philosophical – of creatures: the crybaby. But moments of losing courage belong to a brave life. If we do not allow ourselves frequent occasions to bend, we will be at far greater risk of one day fatefully snapping.

When the impulse to cry strikes, we should be grown up enough to cede to it as we did in our fourth or fifth years. We should repair to a quiet room, put the duvet over our head and allow despondency to have its way.

There is in truth no maturity without an adequate negotiation with the infantile and no such thing as a proper grown – up who does not frequently yearns to be comforted like a toddler.

If we have properly sobbed, at some point in the misery an idea – however minor – will at last enter our mind and make a tentative case for the other side: we’ll remember that it would be quite pleasant and possible to have a very hot bath, that someone once stroked our hair kindly, that we have one and a half good friends on the planet and an interesting book still to read – and we’ll know that the worst of the storm may be ebbing.

THE MONSTERS IN PARIS WHO ARE WATCHING US

When we travel Paris during the day we feel so-called monsters hovering over us. In the night monsters might haunt us too. We can fend the animals off with rational arguments. off course we’ve done nothing wrong. There is no reason to keep apologizing. We have the right to be. To create. But at night, we can forget all weapons of self defence. Why are we still alive? Why haven’t we given up yet? We don’t know what to answer any more.

To survive mentally, we might need to undertake a lengthy analysis of where the monsters come from, what it feeds off, what makes it go on the prowl and how it can be wrestled into submission. One monster might have been born from our father’s mouth, another from our mother’s neglect. Most of them get excited when we have too much work, when we’re exhausted and when the city we live in is at its most frenetic. And they hate early nights, nature and the love of friends.

We need to manage our monsters – each of us has our own versions – with all the respect we owe to something that has the power to kill us. We need to build very strong cages out of solid, kind arguments against them. At the same time, we can take comfort from the idea that the night – time monsters will get less vicious the more we can lead reasonable, serene lives. With enough gentleness and compassion, we can hope to reach a point when, even in the dead of night, as these monsters appear, we will remember enough about ourselves to be unafraid and to know that we are safe and worthy of tenderness.

The monsters hoovering above Paris are not just an evocation of terror; they are also pointing us – more hopefully – to how we might in time tame our monsters through love and reason.

REASONS TO LIVE

When we say that someone has fallen mentally ill, what we are frequently indicating is the loss of long-established reasons to remain alive. And so the tassk ahead is to make a series of interventions, as imaginative as they are kind, that could – somehow – return the unfortunate sufferer to a feeling of the value of their own survival.

This cannot, of course, ever be a matter of simply telling someone in pain what the answers are or of presenting them with a ready – made checklist of options without any sincere or subtle connectioins with their own character. If we are to recover a true taste for life, it can only be on the basis that others haven been creative and accommodating enough to learn the particularities of our upsets and reversals and are armed with a sufficiently complicated grasp of how resistant our minds can be to the so-called obvious and convenient solutions.

We can hang on to one essential and cheering thought: that no life, whatever the apparent obstacles, has to be extinguished. There are invariably ways for it to be rendered liveable again; there are always reasons to be found why a person, any person, might go on. What matters is the degree of perseverance, ingenuity and love we can bring to the taask of rewriting their own story.

Most probably, the reasons why we will feel we can live will look very different after the crisis compared with what they were before. Like water that has been blocked, our ambitions and enthusiasms will need to seel alternative channels down which to flow. We might not be able to put our confidence in our old social circle or occupation, our partner or our way of thinking. We will have to create new stories about who we are and what counts. We may need to forgive ourselves for errors, give up on a need to feel exceptional, surrender worldly ambitions and cease once and for all to imagine that our minds could be as logical or as reliable as we had hoped.

If there is any advantage to going through a mental crisis of the worst kind, it is that – on the other side of it – we will have ended up choosing life rather than merely assuming it to be the unremarkable norm. We, the ones who have crawled back from the darkness, may be disadvantaged in a hundred ways, but at least we will have had to find, rather than assumed or inherited, reasons why we are still here. Every day we continue will be a day earned back from death, and our satisfactions will be all the more intense and our gratitude more profound for having been consciously arrived at.

WHAT IS YOUR STORY?

One of the great impediments to understanding our lives properly is our automatic assumption that we already do so. It’t easy to carry around with us, and exchange with others, surface intellectual descriptions of key painful events that leave the marrow of our emotions behind. We may say that we remember, for example, that we didn’t get on too well’ with our father, that our father was ‘slightly neglectful’ or that going to school was a ‘boring’.

It could, on this basis, sound as if we surely have a solid enough grip on events. but these compressed stories are precisely the sort of readymade, affectless accounts that stand in the way of connecting properly and viscerally with what happened to us and therefore of knowing ourselves adequately. If we can put it in a paradoxical form, our memories are what allows us to forget. Our day-to-day accounts may bear as much resemblance to the vivid truth of our lives as a big part of mythology does.

If this matters, it’s because only on the basis of proper immersion in past fears, sadnesses, rages and losses can we ever recover from certain disorders that develop when difficult events have become immobilized within us. To be liberated from the past, we need to mourn it, and for this to occur, we need to get in touch with what it actually felt like. We need to sense, in a way we may not have done for decades, the pain of our brother or sister preferred to us or the devastation of being maltreated in the study on a Saturday morning.

The difference between felt and lifeless memories could be compared to the difference between a mediocre and a great sculpture. Both will show us an identifable situation, but only a great sculptor will properly seize, from among millions of possible elements, the few that really render the moment charming, interesting sad or tender. In one case we know about this situation, in the other we can finally feel it.

This may seem like a narrow aesthetic consideration, but it goes to the core of what we need to do to recover from psychological complaints. We cannot continue to fly high over the past in our jet plane while refusing to re-experience the territory we are crossing. We need to get out and walk, inch by painful inch, through the swampy realities fo long ago. We need to close our eyes and endure things, methaphorically on foot. Only when we have returned afresh to our suffering and know it in our bones will it ever promise to leave us alone.