This remarkable and monumental seminar of Peter de Kuster at last provides a comprehensive answer to the age-old riddle of whether there are only a small number of ‘basic stories’ in the world. Using a wealth of examples, from ancient myths and folk tales via the plays and novels of great literature to the popular movies and TV soap operas of today, it shows that there are seven archetypal themes which recur throughout every kind of storytelling. Including and most important – the stories you tell yourself, about yourself, to yourself about who you are and what you are doing.

But this is only the prelude to an investigation into how and why we are ‘programmed’ to imagine stories in these ways, and how they relate to the inmost patterns of human psychology. Drawing on a vast array of examples, from Proust to detective stories, from the Marquis de Sade to E.T., Peter de Kuster then leads us through the extraordinary changes in the nature of storytelling over the past 200 years.

Peter analyses why evolution has given us the need to tell stories and illustrates how storytelling has provided a uniquely revealing mirror to mankind’s psychological development over the past 5000 years.

You can watch the movie “Beowulf” following this link

This online seminar opens up in an entirely new way our understanding of the real purpose storytelling plays in our lives, and will be a talking point for years to come.

Practical Information

Start Date: Any Date You Want

Duration: 5 weeks

Time: 1 hour each week personal coaching with Peter de Kuster

Language: English

Price: Euro 699 excluding VAT

Book your place by mailing us at peter@wearesomeone.nl

About Peter de Kuster

Peter de Kuster is the founder of The Heroine’s Journey & Hero’s Journey project, a storytelling firm which helps creative professionals to create careers and lives based on whatever story is most integral to their lives and careers (values, traits, skills and experiences). Peter’s approach combines in-depth storytelling and marketing expertise, and for over 20 years clients have found it effective with a wide range of creative business issues.

Peter is writer of the series The Heroine’s Journey and Hero’s Journey books, he has an MBA in Marketing, MBA in Financial Economics and graduated at university in Sociology and Communication Sciences.

What Can I Expect?

Here’s an outline of “The Hero’s Journey – The Seven Stories of your Life” itinerary.

Journey Outline

PART I THE SEVEN STORIES OF YOUR LIFE

- Overcoming the Monster

- Rags to Riches

- The Quest

- Voyage and Return

- Comedy

- Tragedy

- Transformation

The Dark Power: From Shadow into Light

PART II THE COMPLETE HAPPY ENDING

- The Twelve Dark Characters

- In the Zone

- The Perfect Balance

- The Unrealised Value

- The Drama

- The Twelve Light Charactres

- Reaching the Goal

- The Fatal Flaw

PART III MISSING THE MARK

- The Ego Takes Over

- Losing Your Plot

- Going Nowhere

- Why Sex and Violence?

- Rebellion Against ‘The One’

- The Mystery

PART IV WHY WE TELL STORIES

- Telling Us Who We Are: Ego versus Instinct

- Into the Real World: What Legend are You Living?

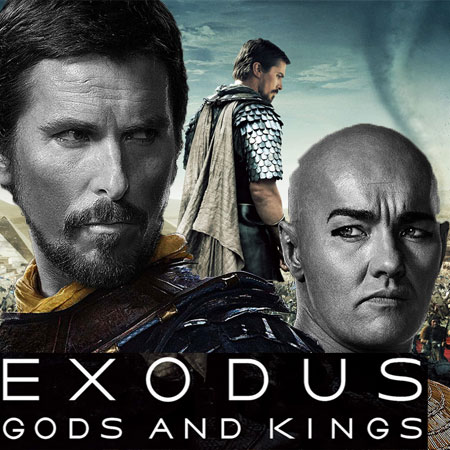

- Of Gods and Men: Finding Your Authentic Story

- The Age of Loki: The Dismantling of the Self

Epilogue: What is Your Story?

Introduction

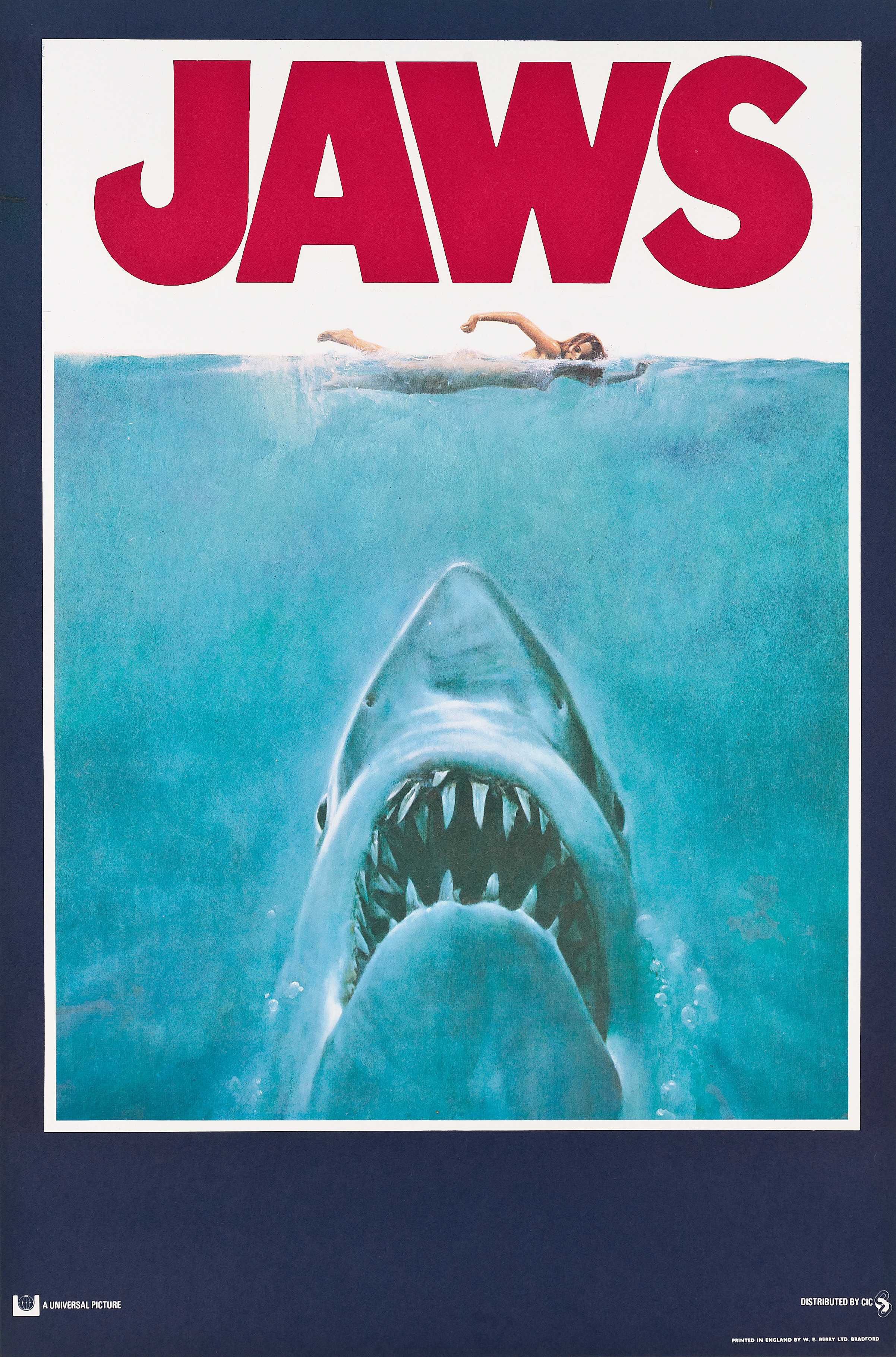

In the mid 1970s queues formed outside cinemas all over the Western world to see one of the most dramatic horror films ever made. Steven Spielberg’s Jaws told how the peace of a little Long Island seaside resort, Amity, was rudely shattered by the arrival offshore of a monstrou shark, of almost supernatural power.

For weeks on end the citizens are thrown into a stew of fear and confusion by the shark’s savage attacks on one victim after another. Finally, when the sense of threat seems almost too much to bear, the hero of the story, the local police chief Brody sets out with two companions to do battle with the monster. There is a tremendous climactic fight, with much severing of limbs and threshing about underwater, until at last the shark is slain. The community comes together in universal jubilation. The great threat has been lifted. Life in Amity can begin again.

It is safe to assume that few of the millions of sophisticated twentieth – century moviegoers who were gripped by this tale as it unfolded from the screens of a thousand luxury cinemas would have paused to think they had much in common with an unkempt bunch of animal-skinned Saxon warriors, huddled round the fire of some draughty, wattle – and – daub hall 1200 years before as they listened to the minstrel chanting out the verses of an epic poem.

The first part of Beowulf tells us how the little seaside community of Heorot is rudely shattered by the arrival of Grendel, a monster of almost supernatural powwer, who lives in the depts of a nearby lake. The inhabitants of Heorot are thrown into a stew of fear and confusion as, night after night, Grendel makes his mysterious attacks on the hall in which they sleep, seizing one victim after another and tearing them to pieces.

Finally when the sense of the threat almost too much to bear, the hero Beowulf sets out to do battle, first with Grendel, then with his even more terrible monster mother. There is a tremendous climactic fight, with much severing of limbs and threshing about underwater, until at last both monsters are slain. The community comes together in jubilation. The great threat has been lifted. Life in Heorot can begin again.

In terms of the bare outlines of their plots, the resemblances between the twentieth century horror and the eight century epic are so striking that they almost be regarded as telling the same story. One which moreover has formed the basis for countless other stories in the literature of mankind, at many different times and all over the world.

So what is the explanation?

You can watch the movie “Jaws” following this link

Why Do We Need Stories?

It is a curious characteristic of our modern civilisation that, whereas we are prepared to devote untold physical and mental resources to reaching out into the furthest recesses of the galaxy, or to delving in to the most delicate mysteries of the atom – in an attempt, to discover every last secret of the universe – one of the greatest and most important mysteries is lying so close beneath our noses that we scarcely even recognise it to be a mystery at all.

At any given moment, all over the world, hundreds of millions of people will be engaged in what is one of the most familiar of all forms of human activity. In oue way or another they will have their attention focused on one of those strange sequences of mental images which we call a story.

We spend a phenomenal amount of our lives following stories: telling them, listening to them, reading them, watching them acted out on the television screen or in fims or on a stage. They are far and away one of the most important features of our everyday existence.

Not only do fictional stories play such a significant role in our lives, as novels or plays, films or operas, comic strips or TV ‘soaps Through newspapers or television, our news is presented to us in the form of ‘stories’. Our history books are largely made up of stories. Even much of our conversation is taken up with recounting the events of everyday life in the form of stories. These structured sequences of imagery are in fact the most natural way we know to describe almost everything in our lives.

But it is obviously in their fictional form that we most usually think of stories. So deep and so instinctive is our need for them that, as small children, we have no sooner learned to speak than we begin demanding to be told stories, as evidence of an appetite likely to continue to our dying day.

So central a part have stories played in every society in history that we take it for granted that the great storytellers, such as Homer or Shakespeare, should be among the most famous people who ever lived. In modern times we have not thought it odd that certain men and women such as John Wayne and Bradd Pitt or Marilyn Monroe and Sophia Loren should come to be regarded as among the best known figures in the world, simply because they acted out the characters from stories on the cinema screen. Even when we look out from our own world into space, we find we have named many of the most conspicuous heavenly bodies – Venus, Mars, Jupiter, Orion, Perseus, Andromeda – after characters from stories.

Yet what is astonishing is how incurious we are as to why we indulge in this strange form of activity. What real purpose does it serve? So much do we take our need to tell stories for granted that such questions scarcely even occur to us.

In fact what we are looking at here is really one mystery upon another. Because our passion for storytelling begings from another faculty which is itself so much part of our lives that we fail to see just how strange it is: our ability to ‘imagine’, to bring up to our conscious perception the images of things which are not actually in front of our eyes. We have this capacity to conjure up the inward images not only of places, people and things not present to our physical senses, but even of things, such as a fire – breathing dragon, which have never existed physically at all.

And it is of course this ability to conjure up whole sequences of such images, unfolding before our inner eye like a film, which enables us to have dreams when we sleep, and when we are awake to focus our attention on these mental patterns, we call stories.

What I set out to show is that the making of these stories serves a far deeper and more significant purpose in our lives than we have realised; indeed one whose importance can scarcely be exaggerated. And the first crucial step towards bringing this into view is to recognise that, wherever men and women have told stories all over the world, the stories emerging to their imaginations have tended to take shape in remarkably similar ways.

The Basic Stories

We are all familiar with the teasing notion that there may be only seven (or six or five or two) stories in the world. It is tantalising.

I found my attention focusing on the 1001 great stories I have ever read or seen. They included stories in literature like a Shakespeare play Macbeth and Vladimir Nabokov’s novel Lolita, stories in the movies like The Deerhunter, The Godfather, Thelma and Louise, myths like the one of Icarus, legends like Faust. On the face of it, these stories might not seem to have much in common. But what intrigued me was the way, that at a deeper leve, they all seemed to unfold rond the same general story we – as humans – tell ourselves.

Each begins with a hero, or heroes, in some way unfulfilled. The mood at the beginning of the story is one of anticipation, as the hero seems to be standing on the edge of some great adventure or experience. In each case he finds a focus for his ambitions or desires, and for a time seems to enjoy almost dream-like success. Macbeth becomes king, Humbert embarks on his affair with the bewitching Lolita, Icarus discovers that he can fly; Faust is given access by the devil to all sorts of magical experiences. But gradually the mood of the story darkens.

The hero experiences an increasing sense of frustration. There is something about the course he has chosen which makes it appear doomed, unable to resolve happily. More and more he runs into difficulty; everyting goes wrong until that original dream has turned into a nightmare. Finally, seemingly inexorably, the story works up to a climax of violent self-destruction. The dream ends in death.

So consistent was the pattern underlying each of these stories that it was possbile to track it in a series of five identifiable stages from the initial mood of anticipation. Through a ‘dream stage’ when all seems to be going unbelievably well, to the ‘frustration’ stage when things begin to go mysteriously wrong, to the ‘nightmare stage’ where everything goes horrendously wrong, ending in that final moment of death and destruction.

Think about a good many dramatic tragedies such as Romeo and Julia or Carmen, the story of Don Juan, the dreams turned to nightmare of those two unhappy heroines, Emma Bovary and Anna Karenina, both ending in suicide. Or Bonny and Clyde, describing the two young lovers who lightheartedly embark on a career as bank robbers and end up riddled with a hail of bullets.

Again and again through the history of storytelling it was possible to see this same theme, of a hero or heroine being drawn into a course of action which leads initially to some kind of hectic gratification and dream-like success, but which then darkens inexorably to a climax of nightmare and destruction. And at this point two questions began to intrude.

First, why was this so? Why has the imagination of storytellers in the history of mankind seemd to form so readily and regularly round the same theme? Why do we recognise it as such a satisfactory shape to a story. Secondly, were there other patterns like this underlying stories, shaping them in quite different ways? What about all those stories which have ‘happy endings’? Were there any similar basic patterns underlying these too?

The Big Question

As soon as I began to look at stories in this light, a number of basic themes in the great stories began to suggest themselves. There were, for instance, all those stories about ‘overcoming of a monster’ like Jaws or Beowulf, in which our interest centers on the threat posed by some monstrous figure of eveil, who is then challenged by the hero and finally, after a climactic battle, killed.

There is the theme of ‘enormous personal growth’ like The Ugly Duckling or Cinderella, where our main interest lies in seeing some initally humble and disregarded little hero or heroine being raised up to a position of immense success and splendour. There were stories based on the theme of a great quest, like the Odyssey or The Lord of the Rings, where our interest centres on the hero’s long, difficult journey towards some distant, enormously important goal.

I embarked on a quest, looking and reading through hundreds of stories of every type of story imaginable: from the myths of ancient Mesopotamia and Greece to James Bond and Star Wars; from ET and Close Encounters of the Third Kind to Proust; from the Marx Brothers to the Marquis de Sade and the Texas Chainsaw Massacre; from the biblical story of Job to Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty -Four; from the tragedies of the Roman myths to Sherlock Holmes; from the operas of Wagner to The Sound of Music; from Dante’s Divine Comedy to Amelie. And it was not long before I began to make a startling discovery. Not only did it indeed seem to be true that there were a number of basic themes or plots which continually recurred in the storytelling of mankind, shaping tales of very different types and from almost every age and culture. Even more surprising was the degree of detail to which these ‘basis story plots’ seemed to shape the stories they had inspired; so that one might find, for instance, a well – known nineteenth-century novel constrected in almost exactly the same way as a Middle Eastern folk tale dating from 1200 years before; or a popular modern children’s story revealing remarkable hidden parallels with the structure of an epic poem composed in ancient Greece.

The stories seemed to be completely diverse: several were classic children’s stories, like Peter Rabbit, Peter Pan and Alice in Wonderland; there were a long list of novels, from Robinson Crusoe to Brideshead Revisited; there were science fiction stories, like H.G. Well’s The Time Machine; there were films ranging from The Third Man and the Wizard of Oz to Gone with the Wind. The further my journey proceeded, the more clearly two things emerged. The first was that there are indeed a small number of story plots which are so fundamental to the way we tell stories that it is virtually impossible for any storyteller ever entirely to break away from them. The second was that, the more familiar we become with the nature of these shaping forms and forces lying beneath the surface of stories, pushing them into patterns and directions which are beyond the storyteller’s conscious control, the more we find that we are entering a realm to which recognition of the plots themselves proves only to have been the gateway. We are in fact uncovering nothing less than a kind of hidden, universal story language; a nucleus of situations and figures which are the very stuff from which stories are made.

And once we become acquainted with this symbolic story language, and begin to catch something of its extraordinary significance, there is literally no story in the world which cannot be seen in a new light: because we have come to the heart of what stories are about and why we tell them.

Our Program

This is a great hero’s journey. Before we embark I should set out a brief route map, so that it will become clear how the different stages of this hero’s journey build on each other in working towards the eventual goal.

This hero’s journey is divided in four parts.

Part One, The Seven Stories of Your Life examines each of the seven great stories of mankind. At first kind, each is quite distinctive. But as we work through the stories, we gradually come to see how they have certain key elements in common, and how each is in fact presenting its own particular view of the same central preoccupation which lies at the heart of storytelling.

Part Two, ‘They Lived Happily Ever After, looks more generally at what all this main story types have in common. In particular we find that they are not only basis plotsto stories but a cast of basic figures who reappear through stories of all kinds, each with their own defining characteristics. As we explore the values which each of these archetypal stories represents, and how they are related, this opens up an entirely new perspective on the essential drama with which storytelling is ultimately concerned. But we also come to see how there are certain conditions which must be met before any story can come to a fully resolved ‘they live happily ever after’ ending. This leads on to part three to an hero’s journey into one of the most revealing of all factors which govern the way stories take shape in the human mind.

The third part of this hero’s journey, ‘The Tragedy” concentrates almost entirely on stories from the last 200 years, explores how and why it is possible in a storyteller’s imagination, for a story ‘to go wrong; or as we say end tragically. The first two parts of the seminar have been primarily concerned with those stories which express the archetypal patterns underlying them in a way which enables them to come to a fully resolved and satisfactory ending. In the third section of the seminar we see how, in the past two centuries, something extraordinary and highly significant has happened to storytelling in the western world. Not only do we look here at such an obvious question as why in recent times storytelling should have shown such a marked obsession with sex and violence. As we look at how each of the basic story plots has developed what may be called its ‘dark’ and ‘light’ versions we see how a particular element of disintegration has crept into modern storytelling which distinguishes it from anything seen in history before. But this in turn merely reveals one of the most remarkable features of how stories take shape in the human imagination; because we also see how those archetypal rules which have governed storytelling since the dawn of history have in no way changed.

This third part of the seminar ends with a discussion on what are arguably the two most centrally puzzling stories produced by the Western imagination, Sophocles’s Oedipus Tyrannos and Shakespeare’s Hamlet. Only at this point have we at last completed the groundwork which is necessary to looking at the deepest questions of all. Just why in our biological evolution has our species developed the capacity to create these patterns of images in our heads? What real purpose does it serve? And how do stories relate to what we call ‘real life’?

These are the questions we look at in the fourth and final part of the journey ‘Why We Tell Stories’, which begins with two very significant types of story we have not looked at before. This relates myths about the creation of the creation of the world and the ‘fall of innocence’ to the evolution of human consciousness and our relations with nature and instinct. In unravelling these riddles, what we see is how and why the hidden language of stories provides us with a picture of human nature and the inner dynamics of human behaviour which nothing else can present to us with such objective authority. We see how a proper understanding of why we tell stories sheds an extraordinary new light on almost every aspect of human existence: on our psychology; on morality; on the patterns of history and politics, the nature of religion and most importantly on the underlying pattern and purpose of our individual lives. We look at the question what the storytellers tell about the power of the story you tell yourself – about yourself – and how you can rewrite your story and thus transform your destiny.

Once Upon a Time

Imagine we are about to be plunged into a story – any story in the world. A curtain rises on a stage. A cinema darkens. We turn to the first paragraph of a novel. A narrator utters the age – old formula ‘Once upon a time….’

On the face of it, so limitless is the human imagination and so boundless the realm at the storyteller’s command, we might think that literally anything could happen next

But in fact, there are certain things we can be pretty sure we know about our story even before it begins.

For a start, it is likely that the story will have a hero, or a heroine, or both; a central figure, or figures, on whose fate our interest in the story ultimately rests; someone with whom, as we say, we can identify.

We are introduced to our hero or heroine in an imaginary world. Briefly or at length, the general scene is set. The purpose of the formula ‘Once upon a time ‘ whether the storyteller uses it explicitly or not, is to take us out of our present place and time into that imaginary realm where the story is to unfold, and to introduce us to the central figure with whom we are to identify.

Then something happens: some event or encounter which precipitates the story’s action, giving it focus. In fact the opening of the story is governed by a kind of double formula ‘once upon a time there was such and such a person, living in such and such place… then, one day, something happened.’

We are introduced to a little boy called Aladdin, who lives in a city in China… then one day a Sorcerer arrives and leads him out of the city to a mysterious underground cave. We meet a Scottish general, Macbeth, who has just won a great victory over his country’s enemies… then, on his way home, he encounters the mysterious witches. We meet a girl called Alice, wondering how to amuse herself in the summer heat… then suddenly she sees a White Rabbit running past, and vanishing down a mysterious hole. We see the great detective Sherlock Holmes sitting in his Baker Street lodgings… then there is a knock at the door and a visitor enters to present him with the next case.

This event provides ‘the Call’ which will lead the hero or heroine out of their initial state into a series of adventures or experiences which, to a greater or lesser extent, will transform their lives.

The next thing of which we can be sure is that the action which the hero or heroine are being drawn into will involve conflict and uncertainty, because without some measure of both there cannot be a story. Where there is a hero there may also be a villain (on some occasions, indeed, the hero himself may be the villain). But even if the characters in the story are not necessarily contrasted in such black – and – white terms, it is likely that some will be on the side of the hero or heroine, as friends and allies, while others will be out to oppose them.

Finally we shall sense that the impetus of the story is carrying it towards some kind of resolution. Every story which is complete, and not just a fragmentary string of episodes and impressions, must work up to a climax where conflict and uncertainty are usually at their most extreme. This then leads to a resolution of all that has gone before, bringing the story to its ending. And here we see how every story has in fact leading its central figure or figures in one of two directions. Either they end as we say, happily with a sense of liberation, fulfilment and completion. Or they end unhappily, in some kind of discomfiture, frustration or death

To say that stories either have happy or unhappy endings may seem such a commonplace that one almost hesitates to utter it. But it has to be said, simply because it is the most important single thing to be observed about stories. Around that one fact, and around what is necessary to bring a story to one type of ending or the other, revolves the whole of their extraordinary significance in our lives.

It was Aristoteles in Poetics who observed first that a satisfactory story – a story which, as he put it, is a ‘whole’ – must have a beginning, a middle and an end’. And it was Aristotle who, in the context of the two main types of stories first explicitly drew attention to the two kinds of ending a story may lead up to. On the one hand, as he put it in the Poetics, there are tragic stories. These are stories in which the hero’s or heroine’s fortunes usually begin by rising, but eventually ‘turn down’ to disaster (the greek word catastrophe means literally a down stroke, the downturn in the hero’s fortunes at the end of a tragedy). On the other hand, there are, in the broadest sense, comedies: stories in which things initially seem to become more and more complicated for the hero or heroine, until they are entangled in a complete knot, from which there seems no escape. But eventually comes what Aristotle calls the peripeteia or ‘reversal of fortune’. The knot is miraculously unravelled. Hero, heroine or both together are liberated; and we and all the world can rejoice.

This division holds good over a much a greater range of stories than might be implied just by the terms ‘tragedy’and ‘comedy’. Indeed, with qualifications, it remains true right across the domain of storytelling. The plot of a story is that which leads its hero or heroine either to a ‘catastrophe’ or an ‘unknotting’; either to frustration or to liberation; either to death or to a renewal of life. And it might be thought that there are almost as many ways of describing these downward or upward paths as there are individual stories in the world. Yet the more carefully we look at the vast range of stories thrown up by the human imagination through the ages, the more clearly we may discern there are certain continyally recurring shapes to stories. It is at the most important of these underlying shapes of stories that we now look.

Overcoming the Monster

In 1839 a young Englishman, Henry Austen Layard, set out to travel overland to Ceylon, the island now known as Sri Lanka. Halfway through his journey, when he was crossing the wild desert region then known as Mesopotamia, his curiosity was aroused by a series of mysterious mounds in the sand. He paused to investigate them, and thus began one of the most important investigations in the history of archaeology. For what Layard had stumbled on turned to be the remains of one of the earliest cities ever built by humankind, biblical Niniveh.

Over the decades which followed, many fascinating discoveries were made at Niniveh, but none more so than a mass of clay tablets which came to light in 1853, covered in small wedge-shaped marks which were obviously some unknown form of writing. The task of deciphering this ‘cuneiform’ script was to take the best part of the next 20 years. But when in 1872 George Smith of the British Museum finally unveiled the results of his labours, the Victorian public was electrified. One sequence of the tablets contained fragments of a long epic poem, dating back to the dawn of civilisation, it was by far the earliest written story in the world.

The first part of the Sumerian Epic of Gilgamesh tells how the kingdom of Uruk has fallen under the terrible shadow of a great and mysterious evil. The source of the threat is traced to a monstrous figure, Humbaba, who lives half across the world, in an underground cavern at the heart of a remote forest. The hero, Gilgamesh, goes to the armourers who equip him with special weapons, a great bow and a mighty axe. He sets out on a long, hazardous journey to Humbaba’s distant lair, where he finally comes face to face with the monster. They enjoy a series of taunting exchanges, then embark on a titanic struggle. Against such supernatural powers, it seems Gilgamesh cannot possibly win. But finally, by a superhuman feat, he manages to kill his monstrous opponent. The shadowy threat has been lifted. Gilgamesh has saved his kingdom and can return home triumphant.

In the autumn of 1962, 5000 years after the story of Gilgamesh a fashionable crowd converged on Leicester Square in London for the premiere of a new film. Dr No was the first of what was to become, over the next 40 years, the most popular series of films ever made (even by 1980 it was estimated that one or more of the screen adventures of James Bond had been seen by some 2 billion people, then nearly half the earth’s population). With their quintesssentially late – twentieth century mixture of space – age gadgetry, violence and sex, anything more remote from the primitive world of those inhabitants of the first cities who conceived the religious myth of Gilgamesh might seem hard to imagine.

Yet consider the story which launched the series of Bond films that night in 1962. The Western world falls under the shadow of a great and mysterious evil. The source of that threat is traced to a monstrous figure, the mad and deformed scientist Dr No, who lives half across the world in an underground cavern on a remote island. The hero James Bond goes to the armourer who equips him with special weapons. He sets out on a long, hazardous journey to Dr No’s distant lair, where he finally comes face to face with the monster. They enjoy a series of taunting exchanges, then embark on a titanic struggle. Against such near – supernatural powers, it seems Bond cannot possibly win. But finally, by a superhuman feat, he manages to kill his monstrous opponent. The shadowry threat has been lifted. The Western world has been saved. Bond can return home triumphant.

Any story which can make such a leap across the whole of recorded human history must have some profound symbolic significance in the inner life of mankind. Certainly this is true of our first type of story, the plot which may be called ‘Overcoming the Monster’.

The Essence of the Monster

The realm of storytelling contains nothing stranger or more spectacular than the terrifying, life-threatening, seemingly all-powerful monster whom the hero must confront in a fight to the death.

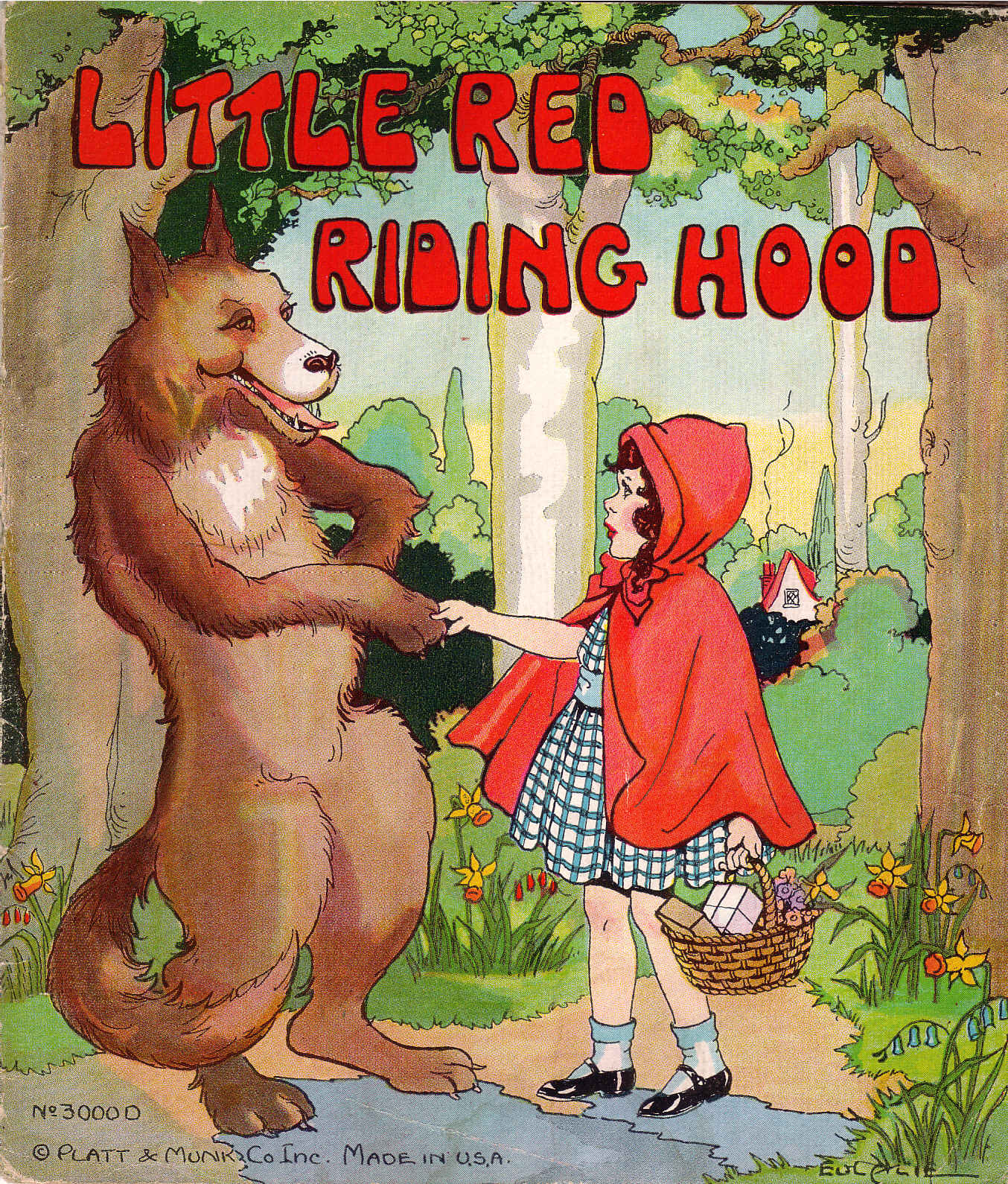

We first usually encounter these extraordinary creations early in our lives, in the guises of wolves, witches and giants of fairy tales. Little Red Riding Hood goes off into the great forest to visit her kindly grandmother, only to find that granny has been replaced by the wicked wolf, whose only desire is to eat Red Riding Hood. In the nick of time, a brave forester bursts in to kill the wolf with his axe and the little heroine is saved.

Hansel and Gretel are cruelly abandoned to die in the forest, where they meet the apparantly kindly old woman who lives in a house made of gingerbread. But she turns out to be a wicked witch, whose only wish is to devour them. Just when all seems lost, they manage to push her into her own oven and burn her to death, finding, as their reward, a great treasure with which they can triumphantly return home.

Jack climbs his magic beanstalk to discover at the top a new world, where he enters a mysterious castle belonging to a terrifying and bloodthirsty giant. After progressively enraging this monstrous figure by three successive visits, each time managing to steal a golden treasure, Jack finally arouses the giant to what seems like a fatal pursuit. Only in the nick of time does Jack manage to scramble down the beanstalk, and bring it crashing down with an axe. The giant falls dead to the ground and Jack is left to enjoy the three priceless treasures he has won from its grasp.

The essence of the ‘Overcoming the Monster’ story is simple. Both we and the hero are made aware of the existence of some superhuman embodiment of evil power. This monster may take human form (e.g. a giant or a witch), the form of an animal (a wolf, a dragon, a shark) : or a combination of both (the Minotaur, the Sphinx). It is always deadly, threatening an entire community or kingdom, even mankind and the world in general. But the monster often also has in its clutches some great prize, a priceless treasure.

So powerful is the presence of this figure, so great the sense of threat which emanates from it, that the only thing which matters to us as we follow the story is that it should be killed and its dark power overthrown. Eventually the hero must confront the monster, often armed with some kind of ‘magic weapons’ and usually in or near its lair, which is likely to be in a cave, a forest, a castle, a lake, the sea, or some other deep and enclosed place. Battle is started and it seems that, against such terrifying odds, the hero cannot possibly win. Indeed there is a moment where his destruction seems all but inevitable. But at the last moment, as the story reaches its climax, there is a dramatic reversal. The hero makes a ‘thrilling escape from the death’ and the monster is slain. The hero’s reward is beyond price. He wins the treasure. He has liberated the world – community, kingdom, the human race – from the shadow of this threat to its survival. And in honour of his achievement, he may well go on to become some kind of ruler.

The Monster in Greek Myths

There have been few cultures in the world which have not produced some version of the Overcoming the Monster story. But a civilisation we particularly associate with such stories is that of the ancient Greeks, whose mythology was swarming with monsters of every kind, from the original Titans overcome by Zeus or the one-eyed giant Polyphemus blinded by Odysseus to the mighty Python strangled by Apollo or the riddle-posing Sphinx who could correctly answer her riddle (for which he was chosen to be king over Thebes).

One of the most celebrated of the Greek monster – slaying heroes was Perseus, who had to overcome not one monster, but two, one female, one male. When, as a young boy, he is cast adrift in the world with his beautiful mother, the Princess Danae, the two fall under the shadow of the cruel tyrant Acrisius, who demands that Danae should succumb to his advances. In a desperate bid to save his mother from this fate, young Perseus offers to perform any task the tyrant should set him. The cruel Acrisius therefore sends the boy off to the end of the world to obtain the head of the dreadful Gorgon Medusa, the mere sight of whose face is sufficient to turn a man to stone.

Perseus is equipped by the gods with magic weapons, a pair of winged sandals, enabling him to fly, a ‘helmet of invisibility’ and a brilliantly polished shield, in which he will be able to see the Medusa’s reflection without having to look at her directly. Perseus reaches the Gorgon’s lair at the Western edge of the world, and severs the Medusa’s snake-covered head. It might seem that he has triumphantly concluded the task that has been set him; but we now learn that this was merely the essential preparation for a further immense task which awaits him on his journey home. As he flies back with his prize, he looks down to see a beautiful, weeping Princess Andromeda, chained to a rock by the sea. She has been placed there as tribute to appease a fearsome sea-monster, which has been sent by Poseidon to ravage her father’s kingdom. Perseus sees the huge reptile rising out of the deeps to seize Andromeda and swoops down to engage in battle. He is able to use the trophy of his first victory, the head of Medusa, to turn the monster to stone. He is rewarded with the hand of the Princess, for liberating her father’s kingdom from the awful threat. He returns home, where he uses the Medusa’s head to turn the tyrant Acrisius to stone, and eventually goes on to become king of Argos.

Another celebrated monster – slayer was Theseus, who also grows up alone in the world with his mother. On coming of age he goes to rejoin his father, King Aegeus in Athnes, having to kill a series of monsters and villains on the way. But when he arrives he finds his father’s kingdom under a terrible shadow, cast by a rival kingdom across the sea in Crete, ruled over by the grim tyrant King Minos.

Every ninth year the Athenians must pay a tribute to the tyrant, by sending the flower of their city’s youth to feed the frightful monster the Minotaur, half – bull, half man, which lives iat the heart of the mighty Labyrinth. A dark, enclosed stone maze from which no one has ever found a way out. Theseus volunteers to lead the party of young men and maidens who are to be sacrificied to this creature; and on arriving in Crete he wins the love and support of the tyrant’s daughter Ariadne, who secretly supplies him with the ‘magic aids’, a sword and a skein of thread, he needs to win victory.

Finding his way to the centre of the Labyrinth, unravelling the thread, he confronts the Minotaur and kills it. Ariadne’s thread enables him to retrace his way back through the maze of tunnels to the open air. It is true that, when they then flee together back to Athens, Theseus abandons his Princess on the island of Naxos. And as he comes within sight of the mainland, and forgets to hoist a white rather than a black sail to show his father that he has returned victorious, King Aegeus throws himself in grief into the sea which afterwards bore his name. But this also means that, like many another monster-slaying hero, Theseus succeeds to the kingdom, becoming the greatest ruler Athens ever had. He also eventually marries the Princess, by making Ariadneś sister Phaedra his queen.

The Monster in the Dark Ages

Another notable constellation of monster tales were those which loomed up in the imaginations of the inhabitants of northern Europe, amid the mists and darkness of the first millenium of the Christian era. The world has rarely seen such a parade of giants, dragons, trolls, treacheous dwarves, foul fiends and ‘loathly worms’ as infested the Norse sagas and Germanic and Celtic epics of these times. And here the hero’s immediate reward for slaying the monster was likely to be a fabulous treasure.

One such tale, later to achieve wider currency from its adaption by Wagner, was the episode in the Volsunga Saga which tells of how the young hero Sigurd, with the aid of his ‘magic weapon’, the great sword Gram, slays the horrible monster Fafnir, who sits in the middle of a wilderness brooding over a great treasure, which includes access to all sorts of runic knowledge, such as an understanding of the song of the birds. But he then goes on to discover ‘the beauteous battle-maiden’ Brynhild, lying asleep on a mountain top guarded by a ring of magic flames which only the true hero can enter; and it is the treasures and the secret knowledge he has won from his victory over Fafnir which enable him to waken her and win her love.

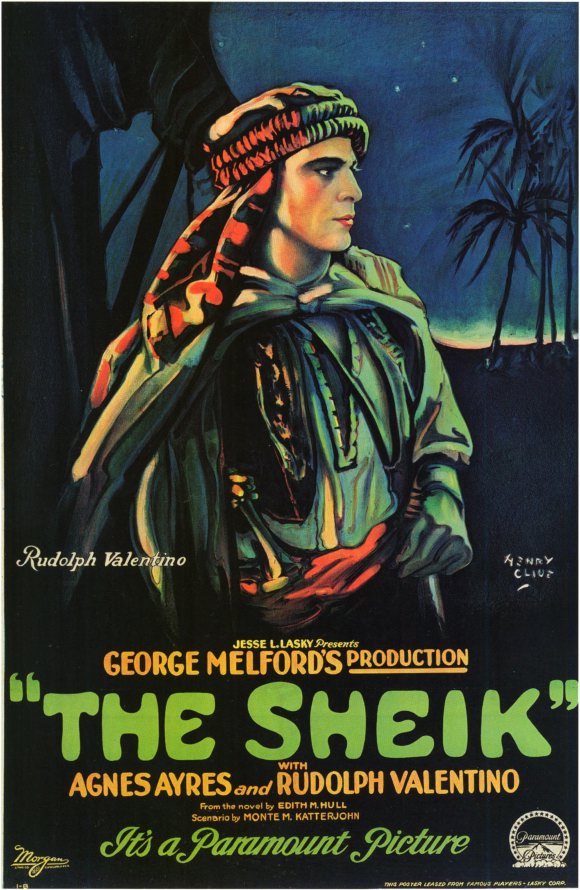

Another celebrated Overcoming the Monster story from the Dark Ages is that of Beowulf. Again we begin with the familiar image of a kingdom which has fallen under a terrible shadow: the little community of Heorot which is nightly menaced by the predatory assaults of the mysterious monster Grendel. The young hero Beowulf comes from across the sea and eventually in a great nocturnal battle, deals the monster a mortal wound: only to disover when he tracks the trail of Grendel’s blood that he must confront the monster’s even more terrible mother, in the lair at the bottom of a deep lake where she is brooding over the body of her dead son. Although Beowulf’s immediate reward for his victory over the two monsters is a rich hoard of ‘ancient treasures and twisted gold’ from a grateful king whose kingdom he has saved, he then returns home to become king over his own kingdom (many years later, at the end of his life, he has to confront a third monster, in a profoundly symbolic episode which we shall look at much later in this seminar).

Of the many Overcoming the Monster stories thrown up by Christian Europe in the Middle Ages, probably the most familiar is that of St George and the Dragon, which appears to be a Christian adaptation of the Perseus myth. The hero comes to a kingdom which is being ravaged by a dragan and, like Perseus finds a beautiful Princess tethered by the edge of the sea, where she has been placed by her countrymen in a last desperate bid to buy off the monster’s attacks. The monster approaches and George slays him; but unlike Perseus, George is not then able to marry the Princess he has freed. Since this is rather self consciously a ‘Christian’ version of the tale, his reward is simply to insist that all the inhabitants of the country should be baptised: in other words, that they should all succeed in another ‘kingdom’, the kingdom of Christ.

The Bloodsucking Monster

During the centuries of diminishing faith in the supernatural which followed the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, the more obviously fantastic dragons and monsters of old slipped below the horizon of European storytelling (although it never faded away altogether). But then, in a way which to the rationalistic age of the Enlightment or even through most of the literal, materialistic Victorian era would have seemed wholly improbable, fabulous and terrifying ‘monsters’ came back into vogue in a quite remarkable fashion.

It all happened quite suddenly, in the closing years of the nineteenth century. Over the previous 100 years there had been a number of premonitory signs notably in the taste for ‘Gothic horror’ which had been such an important reflection of the rise of the Romantic movement with stories as Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. But in the space of just a few years in the 1890’s there appeared in England a rash of stories of the kind which have played such a dominant part in popular entertainment ever since – ghost stories, tales of horror, science fiction – in which monsters of the most grotesque and improbable variety once again surged to the forefront of Western popular storytelling.

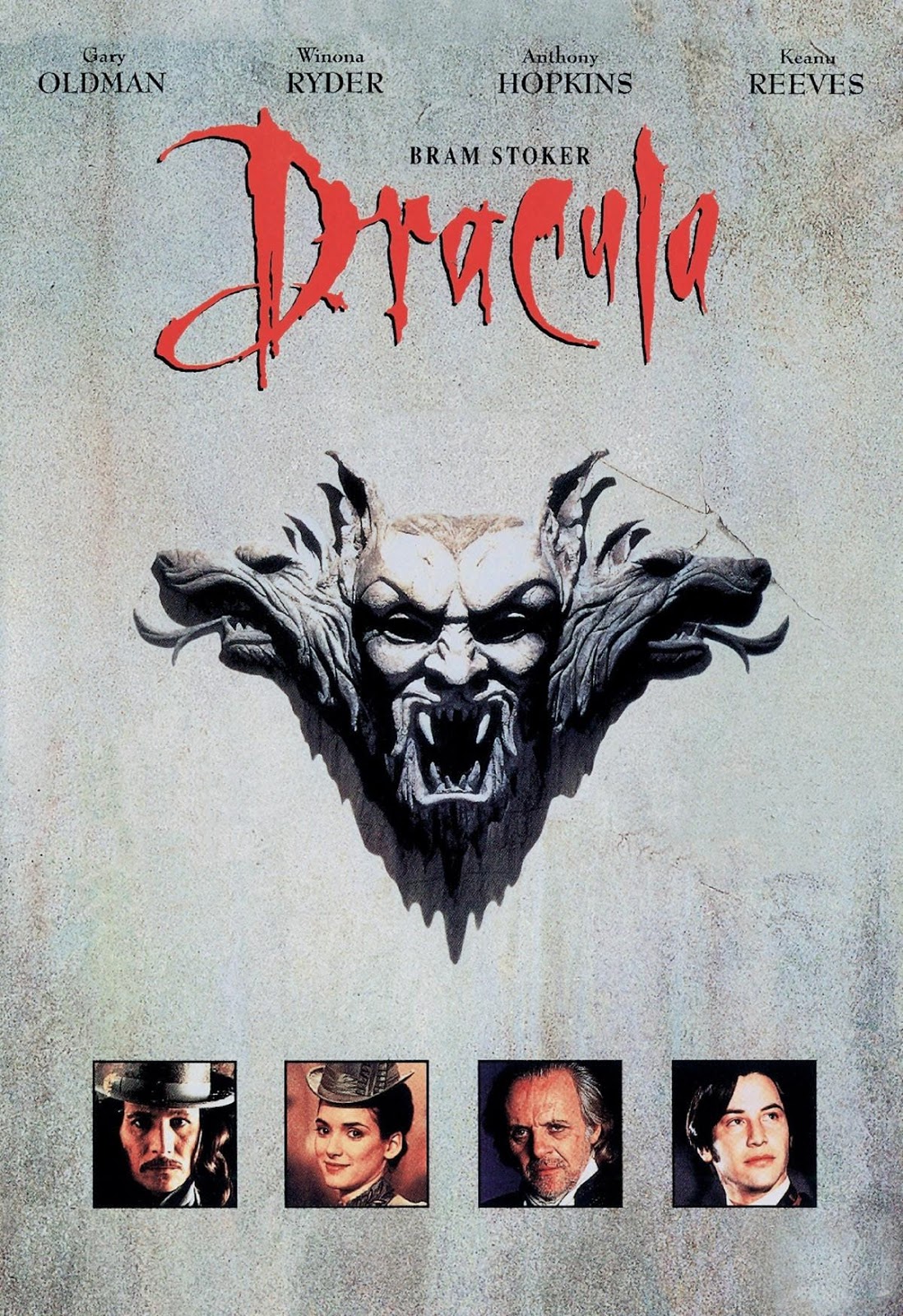

An Anglo-Irish former civil servant, Bram Stoker published in 1897 Dracula. Stories blood-drinking vampires had been told at various times before in history but Stoker’s version was conceived on a new plane of horror. The story divided in two parts. In the first, the hero, a young English lawyer named Harker, makes a visit to a mysterious, ruined castle deep in the wolf-infested forests of Transylvania. There is an air of indescribable evil, both about the place and about his client, Count Dracula, a man with sharp, protruding teeth and unnaturally red lips.

Harker discovers that he is trapped by a man who can crawl face downwards on the castle wall by moonlight; whom he finds one day lying as if dead, ‘bloated’with blood, ‘like a filthy leech, exhausted with his repletion’ ; who seems to be in command of a whole army of equally horrible supernatural spirits.

Just how the hero escapes from seemingly certain doom is never made clear, but the second part of the story tells of how Dracula ‘invades’ England, and in particular the battle by Harker and a group of friends to prevent the monster taking over two young girls, one of them Harker’s intended wife Mina, to recruit them into his shadowy army of the living dead. The first of them, Mina’s friend Lucy, falls fatally into Dracula’s power. Having destroyed one ‘princess’, Dracula then turns his nocturnal attacks on the other, the hero’s financée Mina. Gradually we see her sinking away into the monster’s deadly power. Harker and his friends eventually Dracula down and pursue him back to his Transylvanian lair where, just in the nick of time before Mina finally expires, they manage to operate their ‘magic weapon’by plunging a stake into the monster’s heart (the only way a vampire can be killed).

‘before our very eyes, and almost in the drawing of a breath, the whole body crumbled into dust and passed from our sight.’

Mina – and mankind – are saved!

In 1898, the year after Dracula, H.G Wells published ‘The War of the Worlds’. Again, it was by no means the first science fiction story, but the comparatively cosy fantasies of Jules Verne had contained nothing like this. Puffs of fire are seen on Mars, huge meteorites flash across the sky and some come to earth in southern England. The initial mood of excited curiosity changes to alarm, when it appears that these mysterious, half buried cylinders contain life.

The nightmarish realisation dawns that these huge ‘fungoid’monsters climbing out of the cylinders are implacably hostile. They assemble great ‘tripod machines’whih stride across the countryside, armed with ‘Heat Rays’and the deadly ‘Black Smoke against which mankind has seemingly no defence. Southern England is laid waste, as towns and cities burn, corpses pile up and the countryside is gradually submerged beneath the horrible ‘Red Weed’. Can the world survive?

Then as the hero cowers in a cellar in south London, all alone and imagining his wife to be dead, he hears floating across the deserted, half ruined city a ghastly, wailing cry ‘Ulla, ulla, ulla. He cautiously picks his way up to Primrose Hill, where he sees the great machines standing silent, the dead Martians hanging out of them as strips of decaying meat. The invading monsters have fallen prey to humble earthly bacteria, the one thing against which they had no defence. Mankind is saved and the story ends on the image of the hero being joyfully reunited with his wife who turns out, like him, to have miraculously survived.

The Purpose of the Monster

What is this monster which, since time immemorial, has so haunted the imagination and fantasies of mankind?

It is a question of deepest importance to the understanding of stories, relevant to tales of many kinds other than just those centred on the plot we have been discussing. The question may be put in the singular – speaking of one ‘monster’ rather than many – if only because of the essential characteristics of this creature are so unvarying, regardless of the variety of outward guises in which he (or she) appears.

For a start, throughout the world’s storytelling, we find the monster being described in strikingly similar language. It tends, of course, to be highly alarming in its appearance and behaviour. It may be:

- horrible, terrible, grim, mis-shapen, hate-filled, ruthless, menacing, terrifying

As goes without saying, it is mortally dangerous:

- deadly, bloodthirsty, ravening, murderous, venomous, poisonous

It is deeply and tricky opponent to deal with:

- cunning, treacherous, vicious, twisted, slippery, depraved, vile

There is also often something about its nature which is mysterious and hard to define. It may be:

- strange, shapeless, sinister, weird, nightmarish, ghastly, hellish, fiendish, demonic, dark.

In other words, in its oddly elusive way, we see this ‘night creature’ whether it is a giant or a with, a dragon or a devil, a ghost or a Martian, representing (often vested in a kind of dark, supernatural aura) everything which seems most inimical, threathening and dangerous in human nature, when this is turned against ourselves.

Then there are the monster’s physical attributes. And here we must not be misled by the fact the monster is so often represented as an animal, or even a composite of several animals: e.g. the dragon. Such monsters may be animal in form, but they are invariably invested with attributes no animal in nature would possess, such as a peculiar cunning or malevolence. They are in fact preternatural, having qualities which are at least partly human.

Not Completely Human

There are many monsters in stories which are human, but invested with animal attributes, either directly, like the Minotaur, half-man, half-bull. They are seen as less than wholly human. And even when monsters are shown as entirely human in appearance, they tend to be in some way physically abnormal: abnormally large (giants), abnormally small (dwarves) or in some way deformed (e.g. missing an eye or a limb, or hunchbacked).

By definition, the one thing the monster in stories can never be is an ideal, perfect, whole human being.

Then there are the monster’s behavioural attritutes. We invariably see it acting in one of three roles:

- In its first ‘active’ role, the monster is Predator. It wanders menacingly or treacherously through the world, seeking to force or to trick people into its power.

- The monster’s second, more ‘passive’ role is as Holdfast. It sits in or near its lair, usually jealously guarding the ‘treasure’ it has won into its clutches. It is in this role a keeper and a hoarder, broody, suspicious, threatening destruction to all who come near.

- When its guardianship is in any way challenged, the monster enters its third role as Avenger. It lashes out viciously, bent on pursuit and revenge.

In fact, we may often see the same monster acting out all three roles at different stages of the same story. In Jack and the Beanstalk, for instance, we first see the giant as Predator, prowling about, demanding human food. We next see him as Holdfast, brooding in miserly fashion over his treasures. We finally see him, when Jack steals the treasures, running angrily in pursuit, as Avenger. And the point about these three roles is that they represent all the main aspects of the way human beings behave when acting in an entirely self-seeking fashion. When people are at odds with the world, behaving selfishly or anti-socially, they are after ‘something’ as Predators; wanting grimly to ‘hold on to something, as Holdfasts; or as Avengers, resentfully trying ‘to get their own back’.

One may sum up by saying that, physically, morally and psychologically, the monster in storytelling thus represents everything in human nature which is somehow twisted and less than perfect. Above all, and it is the supreme characteristic of every monster who has ever been portrayed in a story, he or she is egocentric. The monster is heartless; totally unable to feel for others, although this may sometimes be disguised beneath a deceptively charming, kindly or solicitous exterior; its only real concern is to look after its own interests, at the expense of everyone else in the world.

Such is the nature of the figure against whom the hero is pitted, in a battle to the deat. And we never have any doubt as to why the hero stands in opposition to such a centre of dark and destructive power: because the hero’s own motivation and qualities are presented as so completely in contrast to those ascribed to the monster. We see the hero being drawn into the struggle not just on his own behalf but to save others: to save all those who are suffering in the monster’s shadow; to free the community or the kingdom the monster is threatening; to liberate the ‘Princess’ it has imprisoned. The hero is always shown The hero is always shown as acting selflessly and in some higher cause, in a way which shows him standing at the opposite pole to the monster’s egocentricity.

And even though the monster wields such terrifying power that, almost to the end, its dark presence is the dominant factor holding sway over the world described by the story, it has one weakness which ultimately renders it vulnerable. Despite its cunning, its awareness of the reality of the world around it is in some important respect limited. Seeing the world through tunnel vision, shaped by its egocentric desires, there is always something which the monster cannot see and is likely to overlook. That is why, by the true hero, the monster can always in the end be outwitted: as was the mighty Goliath by little David, who was able to stay out of reach of the giant’s strength by using his little slingstones. As was the Medusa by Perseus with his reflecting shield, which meant he did not have to look at her directly; as was Minos by his own daughter secretly presenting Theseus with the sword and thread; as were Well’s Martians by their overlooking even something as apparently insignificant as the destructive power of bacteria. It is this fatal flaw in the monster’s awareness which is ultimately its undoing. Despite its power, the monster is shown not only as heartless and egocentric. It is also, in some crucial respect which turns the day, blind.

The Monster in Melodrama

The shadowy figure is of the greatest significance in stories, not just because of the more obvious and lurid appearances it makes in myths, folk tales, horror stories and science fiction, but because to a greater or lesser extent these characteristics describe the dark, negative and villainous characters who appear in stories of almost every kind.

Indeed, once we have identified the monster’s essential attributes, we can see how there are a great many types of story shaped by the Overcoming the Monster plot other than just the more literal examples we have so far been looking at. As in Melodrama.

There were, for instance, many of those melodramatic tales beloved of the nineteenth century which may be caricatured as ‘the hero having to rescue the beautiful maiden from the clutches of the wicked Sir Jasper’. A familar example is Charles Dickens’s Nicholas Nickleby. Like the hero of many a fairy tale, young Nicholas is left orphaned by the death of his father and having to provide for his penniless mother and sister. He is taken in hand by a seemingly kind uncle, Ralph, who arranges a teaching post for him at the grim Northern school Dotheboys Hall. And when we meet the tyrannical owner of this establishment Mr Squeers we might think we had met the story’s chief ‘monster’. But no sooner has Nicholas overcome this particular villain, by giving him a thrashing and escaping from the school, than it gradually emerges that the hero and his family are in fact threatened by a kind of mysterious, Hydra headed conspiracy, of which Squeers had merely been one lesser ‘head’.

In fact the chief monster at the centre of this web of evil is the wicked usurer, Uncle Ralph himself. The action centres first on the liberation of Nicholas’s sister Hawk, another ‘Hydra-head; then on the even more hazardous rescue of his own chosen ‘Princess, the beautiful Madeleine Bray, from a vile plot to marry her off to yet another Hydra – head, the unpleasant old Arthur Gride.

Finally all Ralph’s wicked schemes are exposed and brought to naught. Nicholas, the triumphant hero, is free to marry his ‘Princess’ who, it is then discovered, has inherited a great ‘treasure’ from her father.

The Monster in War Movies

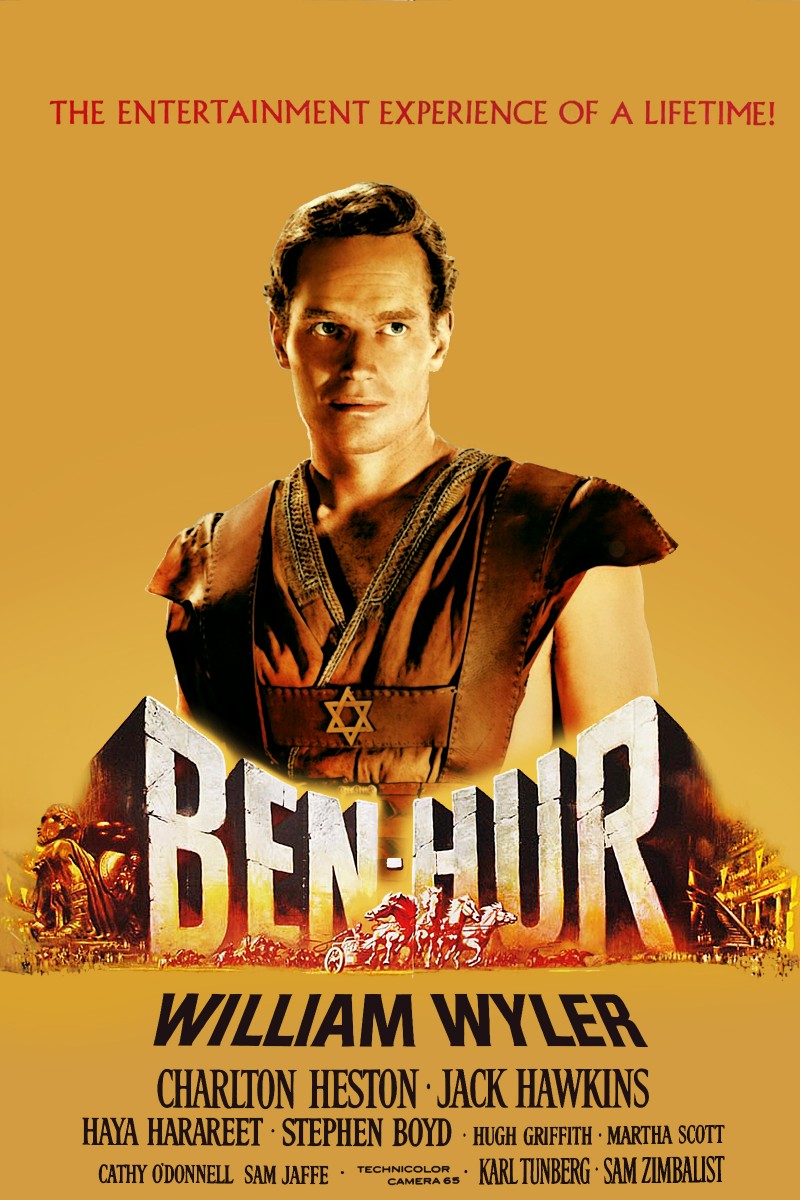

A very different kind of tale shaped by the Overcoming the Monster theme is the war story, particularly those set at the time of the Second World War. In the past 70 years the immense drama of World War Two has inspired many more fictional stories than any other real – life episode in history. One reason for this was the way Hitler’s Nazis, and to a lesser extent their Japanese allies, provided storytellers with such an extraordinarily rich store of ‘monster-imaginery’.

In countless films from the 1940’s on, we saw Hitler’s Germany cast as invading Predator, with all the diabolic paraphernalia of the blitzkrieg as Holdfast, exercising ruthlessly tyrannical sway over Occupied Europe; or as Avenger, lashing out at resistance heroes, prison camp escapers or anyone else who dared challenge its murderous authority. The vast majority of such stories were based on the plot of Overcoming the Monster, with the underlying pattern of the story in almost every instance the same. At first there is a preparatory stage of anticipation, as of some great forthcoming ordeal. We see the seemingly insuperable power of the German war machine. There is then a gathering sense of danger, as battle is joined, and the heroes seem to have all the odds stacked against them. Then comes the climactic confrontation and finally the miraculous victory. The Nazi (sometimes Japanese) monster is overthrown. The dark armadas of the Luftwaffe (as in Battle of Britain) are hurled back. The great Predator ship (as in The Sinking of the Bismarck) is destroyed. The invasion of Europe (as in the Longest Day) is successfully achieved. The Nazi’s counter-offensive (as in the Battle of the Bulge) is fought off. The beautiful city of Paris (in Is Paris Burning), like a rescued Princess, is at the last moment saved.

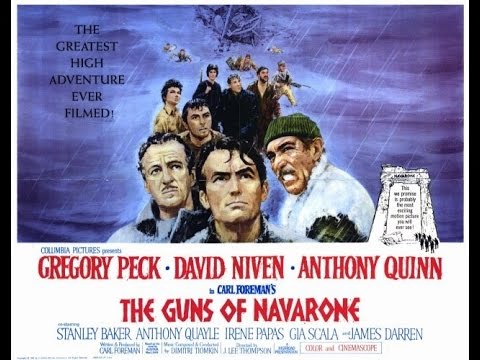

But never far from the surface of these apparently modern, and even ‘historically accurate’ accounts were the patterns and imaginery of a story as old as the imagination of man. Alistair Maclean’s The Guns of Navarone, a typical fictional Second World War adventure story, tells how five heroes land on a closely guarded Aegean island to destroy two huge German guns concealed in a clifftop cave, which holdfast like dominate a narrow strait. We are aware that this is the only way through which a large number of beleaguered Allied soldiers can be lifted to safety from a nearby island. Thousands of lives are at the mercy of these mighty engines of destruction. Painfully the heroes make their way across the island, narrowly escaping every kind of disaster, until at last they reach the cave and see, against the night sky:

‘crouched massively above, like some nightmare monsters from another and ancient world, the evil, the sinister silhouettes of the two great guns of Navarone.’

Evading detection as they catch the sentries on their ‘blind spot’ the heroes fix their little explosive charges against the guns, like ‘magic weapons’ against something so massive and overpowering. Finally, as the ‘tremendous detonation tore the heart out of the great fortress it is at one level not just the guns of Navarone which are being destroyed, but Humbaba, the Minotaur, Dracula and every other monster who has ever been. After the mounting suspense of the long ordeal, penned in at every moment by the prospect of sudden death, liberation is here! Life has triumphed over death! Humanity can breathe again!

The Monster in Hollywood Western

So basic is the outline of the Overcoming the Monster plot that there is almost no limit to the variety of story-types it can give rise to. We can recognise it wherever our interest in a tale is centred on the steady build-up to a climactic battle between the hero and some dark, threatening figure, or group of figures, whether this be the wicked witch in a fairy tale or invading aliens from outer space, Spielberg’s flesh-eating dinosaurs in Jurassic Park or the outlaw gang in a Western.

The Magnicifent Seven begins in classic Overcoming the Monster style by showing a community living under the shadow of a monstrous threat: a little Mexican farming village being terrorised by an outlaw gang, led by the villainous Calveros, who regularly arrive at the village to rob the famers of food. We see one such predatory visit, when one old farmer tries to protest. Calveros shoots him in front of the villagers, thus underlining just what a heartless and predatory tyrant he is.

A wise old man living nearby advises the farmers that the only way to stop this reign of terror is that they should buy guns. Three of them ride over to the American border where they see two professional gunmen ( played by Yul Brynner and Steve McQueen) fearlessly standing up to the inhabitants of a small town in insisting that an Indian who has died in the town should be buried in the whites only cemetery. This establishes that the two heroes are not racially prejudiced and are willing to fight against injustice. For a small sum of money, all they can afford, the Mexicans persuade the two gunmen to come back to their village to defend them against the outlaws. The two recruit another five, and the seven gunmen arrive in the village to train its inhabitants in self-defense.

When Calveros’s gang next returns it is beaten off with heavy losses. But when the seven ride out into the countryside to see what the gang is up to, Calveros outwits them by secretly occupying the village in their absence. When they return they discover they have fallen into his clutches. In front of the cowed villagers, he removes their guns, and allows them to leave. Foolishly, however, showing the monster’s blind spot, he allows their guns to be returned to them when they have left town. He cannot imagine that, as mere hired gunmen, they will not just ride away to avoid any further trouble, leaving him free to carry on oppressing the villagers. But, bruised by the humiliation, the seven ride back into town for a final climactic battle, in which Calveros and his gang are routed, not least because the villagers recover their courage and join in. Four of the seven are dead. One decides to remain in the village because he has fallen in love with a village girl, which allows the story to end on the image of a man and woman united in love. But the two original brave heroes ride off into the wide blue yonder, having overcome the monster and saved the community.

Another classic Hollywood Western based on this plot was Fred Zinnemann’s High Noon (1952. Again we see a community living under the shadow of a monstrous outlaw gang., the little town of Hadleyville in the old West. The story begins on the morning when the hero Will Kane (played by Gary Cooper) having resigned as town marshal is getting married to the pretty young Quaker (Grace Kelly). No sooner is the ceremony over than Kane unpins his badge of office and he and his new bride prepare to leave the town for ever. But then shocking news arrives. Some years earlier Kane had been responsible for arresting Frank Miller, a psychopathic gang leader who terrorised the town, and now Miller has been released from prison. He is heading back to Hadleyville on the noon train, due to arrive in just two hours time. The three unsavoury members of his gang are already at the station waiting for him and for the moment when they can settle their score with Kane and reimpose their reign of terror.

Scarcely have the newly-weds set out from town than Kane realises he cannot leave the townsfolk defenceless. He turns back, hoping to round up a posse of townsfolk to help defeat the gang. But the people are so cowed that they dare not help. Just like some of the villagers in The Magnificent Seven they would much rather Kane left them, in the appeasing hope that trouble might be avoided. Amy herself, as a Quaker, refuses to have anything to do with bloodshed and leaves for the station to catch the same train. Suspense mounts, as clocks tick away the two hours, and Kane finds no one to support him. At last a distant whistle is heard from across the plan. The train approaches. Miller disembarks to join his gang and the four men swagger into the now deserted town looking for a showdown with the solitary hero.

The gun battle begins and Kane manages to kill first one of his opponents, then another. But finally he is trapped in a building, its exits covered by Miller and the other outlaw. It seems all is lost and he is at their mercy. Then a miracle takes place. A shot rings out from across the street and a third villain lies dead. At the last minute Amy has jumped off the train and returned to town and she is standing at a window with a smoking gun in her hand. Frank Miller seizes her, pushes her out in front of him into the street and tells the hero, that unless he comes out to surrender,s he will be killed. As Kane emerges, Miller pushes Amy aside to fire, bravely she jogs his arm, giving the hero a chance to get his shot in first. All four outlaws are dead. Hero and heroine embrace as the shamefaced townsfolk emerge from their hiding places to cluster round their saviours. The loving couple can at last ride happily off together to start their new life.

Beneath this comparatively modern trappings (guns, the train) there is nothing about this story which could not have been presented in the imagery of an ancient myth or egend: with the little town as a kingdom threatened by the approach of a terrifying dragon, and Kane as a princely hero who, against all odds, finally slays the monster – although, like Theseus, he only manges to do this with the help of a loving ‘Princess’, who unexpectedly comes to his aid just when all seems lost.

The Monster in Thrillers

Another genre of story usually shaped by the Overcoming the Monster plot is the thriller: and here again we see how often thriller writers unconsciously fall back on the age-old stock of ‘monster imagery’, as they look for the kind of language which will help them to build up their hero’s chief antagonist into a shadowy figure of immense menace and evil.

In that early thriller-adventure story Dumas’s The Three Musketeers (1844), the action centres on the long struggle between the hero D’Artagnan and the evil Lady de Winter, who lures the hero’s chosen Princess, the beautiful young Madame de Bonancieux, into her clutches. When we look at the imagery used to describe Lady de Winter, whose sinister influence extends all over France, we see her not only characterised explicitly as ‘a monster’ who has ‘committed as many crimes as you could read of in a year’, but as a ‘panther’, a ‘tiger’, a ‘lioness’ and several times as ‘a serpent’.

When in The Final Problem Conan Doyle wished to create a villain who was at last a worthy match for the powers of his hero Sherlock Holmes, he conjured up the ‘reptilian’ Moriarty, like Dracula a ‘fallen angel’, a man of ‘extraordinary mental powers’ who has perverted them to ‘diabolic ends’. ‘For some years past’ says Holmes, ‘I have been conscious of some deep organising power which stands forever in the way of the law’. He realises that it is the shadowy Moriarty, eternally elusive, a master of disguise, ‘the most dangerous criminal in Europe’ who:

‘sits motionless, like a spider in the centre of his web, but that web has a thousand radiations, and he well nows every quiver of them’.

The thrillers of John Buchan made lavish use of similar imagery. In ‘The Thirty Nine Steps, for instance, the hero Richard Hannay learns of the materialising of some vast, shadowy threat to the ‘peace of Europe’: behind all the governments and the armies, there was a big subterranean movement going on, engineered by some very dangerous people. When he tracks down the chief villain at the heart of this immense conspiracy to a remote Scottish moor, he is a German master-spy described as ‘bald-headed’ like ‘a sinister fowl’.

In those most successful of all twentieth – century thrillers Ian Fleming’s James Bond stories, the imagery again and again quite explicitly builds up the ‘monster’ with echoes of myth and fairy tales. Le Chiffre, the villain of Casino Royale is ‘a black-fleeced Minotaur’; Sir Hugo Drax in Moonraker has ‘a hulking body’ with ‘ogre’s teeth’; Mr Big in Live and Let Die has ‘a great football of a head, twice the normal size and nearly round’ the villain of Dr No, bald and crippled, with steel pincers instead of arms, ‘looked like a giant venomous worm, wrapped in grey tin-foil’.

Indeed one of the key reasons for the initial success of the Bond stories, even before they wer translated to the cinema screen was precisely the way they tapped so unerringly into those springs of the imagination which had given rise to similar stories for thousands of years. So accurately did the typical Bond novel follow the age old archetypal pattern that it might almost serve as a model for any Overcoming the Monster story.

As conceived by Fleming, the basic Bond story unfolds through five stages rather like this:

- The Call to Adventure. The hero, a member of the British Secret Intelligence Service, is summoned by ‘M’, head of the service and told of suspicious goings-on somewhere in the world which appear to pose a deadly threat to Britain, the West or mankind as a whole.

The Monster in Science Fiction

Just when Ian Fleming was publishing his first Bond novels, some of his British contemporaries were producing particularly striking examples of that type of story which in the past century has revived the imagery of archetypal monsters more grotesquely inhuman than anything seen in storytelling since the Dark Ages and the myths of ancient Greece. In the early 1950’s, as the world awaited the imminent arrival of the space age, two genres of science fiction story swept into fashion: the first, following H.C. Wells centred on deadly invasions of the earth by monsters from outer space; the other featuring some world threatening catastrophe unleashed by mankind’s ow growing technological ability to interfere with nature.

In 1953, just after the Queen’s Coronation had prompted millions of Britons to install their first primitive television sets, the first serial on the new medium to catch the nation’s imagination was Nigel Kneale’s The Quatermass Experiment, with its hero a shrewd and robust scientist, Professior Bernard Quatermass. As head of the world’s first manned space-flight project, Quatermass is horrified when the spaceship returns with only one of the three astronauts alive. Gradually it becomes clear that the survivor, Victor Caroon, has not only absorbed the personalities of his two dead colleagues but has been taken over by some diabolically ingenious extra-terrestrial power which is using his body as a vehicle to take over the earth.

The ‘frustration stage’ sets in when Caroon appears to be turning into a cross between a cactus and a fungus., then disappears. When next sighted he has become a huge and fast-profilerating fungoid monster spreading over the interior of Westminster Abbey, about to throw out millions of spores which will wipe out humanity, allowing the aliens to take over. In this ‘final ordeal’ Quatermass confronts the monster and somewhat implausibly persuades the three human beings who are still mysteriously part of it to resist its influence, even though this will involve their own suicide. This leads to the ‘miraculous escape’by which humanity is saved.

The underlying five-stage pattern of these stories is only too familiar. As each of them begins with the arousal of curiosity, then continues with frustration as the monster’s true deadly nature becomes apparent, leading to a ‘nightmare stage’ when catastrophe seems inevitable, finally ending in the ‘miraculous escape’, their pattern is exactly the same as that which we first came across in some of the simplest stories of our childhood, such as Jack and the Beanstalk or Little Red Riding Hood.

The Monster in Star Wars

As a last example, to underline just how fundamental a pattern to storytelling this is, we may look at what became the most successful science fiction film ever produced in Hollywood, George Lucas’s Star Wars (1977)

The Star Wars story is set in the distant future, when the many planetary worlds of our galaxy are ruled by one government. For centuries this had exercised benevolent sway as ‘the Republic’, with the aid of the brave and honourable Jedi Knights. But the government has now been seized by a conspiracy of power-crazed politicians, bureaucrats and corporations, headed by a shadowy ‘Emperor’ and no-one, it seems wields greater power in this tyrannical new ‘Empire’ than the ruthless ‘Dark Lord’ Darth Vader, once himself a Jedi knight, now, like Lucifer, a ‘fallen angel’. Scattered across remote reaches of the galaxy dispossessed supporters of the old order, ‘the rebel Alliance’, are hoping one day to overthrow the dark Empire, to reclaim the universe for the forces of light.

The story opens with a rebel spaceship being attacked by an ‘Imperial cruiser’ captained by the terrifying Vader, whom we only see hidden in menacing black armour. As his Imperial forces take over the rebel ship, a tiny spacecraft escapes, containing See Threepio and Artoo Deetoo, two ‘androids’or humanised computers, who land safely on the surface of a nearby planet, Tatooine. Still on the rebel ship is the beautiful Princess Leia, daughter of the leader of the rebel Allicance, whom Vader takes prisoner.

We thus begin with the familiar image of a Princess falling into the clutches of the ‘monster’. But the one thing the ‘Dark Lord’ is desperate to discover is the whereabouts of the rebel organisation’s secret headquarters, so he can destroy it, thus making the victory of the Empire complete. What he does not realise is that the resourceful Princess has programmed Artoo Deetoo with this vital information, along with an urgent appeal for help, before the androids bail out. By the fatal mistake of allowing them to escape, because he thinks their little craft is unmanned, the arrogant Vader has revealed a first ‘blind spot’.

Only now do we at last meet the young hero of the story, Luke Skywalker, who lives with his uncle and aount on a lonely farmstead on Tatooine, dreaming of future glory as a space – pilot. When the two androids arrive at the foarm, Artoo lights up with a hologram of the Princess. Luke is at once smitten by her beauty. She utters the baffling message ‘Obi – wan Kenobi, you are my only remaining hope’. Which Luke vaguely connects with a mysterious bearded hermit, ‘a kind of sorcerer’ who lives in an even more remote part of the desert. He and the androids set off to find him and, after Kenobi has miraculously intervened to save them from death at the hands of desert-dwelling monsters, they find themselves in the ‘wizard’s’ cave. The old man reveals he is one of the last surviving Knights of the Jedi, with supernatural powers, and that Luke’s lost father had been another, one of the bravest of all. Interpreting the Princess’s cry for help, Kenobi asks Luke to accompany him on a hazardous mission to rescue her.

This marks the end of the ‘Anticipation Stage’. The hero has received the ‘Call’; giving him and the story a focus. We can see now what the story is centrally to be about; and the hero’s sense of being impelled towards this mysterious new destiny is reinforced when they return to the farmstead to find that the uncle and aunt who have brought him up have been vapourised by Imperial troops. There is nothing left to keep him at home.

Despite further threats, fought off with Kenobi’s supernatural aid, Luke gradually assembles a team to make the journey; and in the nick of time, pursued by Imperial soldiers, they make a ‘thrilling escape’in a deceptively battered old spacecraft, piloted, solely for the money, by a reckless mercenary Han Solo. This enables them to throw off their pursuers as they head off faster than light to their mystery destination. On the journey Kenobi imparts some of the ancient Jedi secrets to Luke, not least the importance of the mysterious ‘force’ with which the Knights learn to ally themselves, giving them supernatural powers. As the wise old man explains, this is ‘an energy field, and something more. An aura that at once controls and obeys, a nothingness that can accomplish miracles’. He describes the optimal experience of ‘flow’. During this phase of the story, the hero and his companions seem to enjoy a magical immunity to danger: the “Dream Stage’. But we are reminded of the dark reality prevailing elsewhere, as we glimpse the Princess being subjected by Vader to horrific tortures, trying to force her into giving up the secret whereabouts of the rebel headquarters, the distant planet Alderaan.

Then suddenly, as they near their destination, they see the horrifying sight of a vast, mysterious man-made structure floating in space ahead of them. It is the Empire’s own secret weapon, the Death Star, a spaceship so powerful it can destroy a whole planet. This is where the Dark Lord Vader is holding the Princess prisoner. Even as they approach, this monstrous engine of death pulverises Alderaan, including the Princess’s father, to atoms. At the same time, the hero and his companions feel their own small spacecraft itself being sucked inexorably down a powerful beam into the heart of the Death Star. As their ship comes to rest it seems they are the monster’s prisoners. Like Bond, when he penetrates the lair of one of his monstrous opponents and falls into his clutches, they have reached the ‘Frustration Stage’.

Now begins the terrible ordeal of the ‘Nightmare Stage’. Pursued all the way threatened by one horror after another they wander through the endless, dark, metallic labyrinth of this huge structure, first to track down and release the Princess from her prison cell; then to thread their way back to their own spacecraft, having first immobilised the gravity beam which had taken it prisoner. Finally, thanks to old Kenobi sacrificing his life in a hand-to-hand struggle with his one time pupil, the Dark Lord, they make their miraculous escape, with the freed Princess on board – hurtling through space to another unknown planet where, hidden beneath ancient ruins in a jungle, is the true secret command headquarters of the rebel Alliance.