“Your story is your life,” says Peter. As human beings, we continually tell ourselves stories — of success or failure; of power or victimhood; stories that endure for an hour, or a day, or an entire lifetime. We have stories about ourselves, our creative business, our customers ; about what we want and what we’re capable of achieving. Yet, while our stories profoundly affect how others see us and we see ourselves, too few of us even recognize that we’re telling stories, or what they are, or that we can change them — and, in turn, transform our very destinies.

Telling ourselves stories provides structure and direction as we navigate life’s challenges and opportunities, and helps us interpret our goals and skills. Stories make sense of chaos; they organize our many divergent experiences into a coherent thread; they shape our entire reality. And far too many of our stories, says Peter, are dysfunctional, in need of serious editing. First, he asks you to answer the question, “In which areas of my life is it clear that I cannot achieve my goals with the story I’ve got?” He then shows you how to create new, reality-based stories that inspire you to action, and take you where you want to go both in your work and personal life.

Our capacity to tell stories is one of our profoundest gifts. Peter’s approach to creating deeply engaging stories will give you the tools to wield the power of storytelling and forever change your business and personal life.

Join Peter for a truly transformational vacation for the mind.

Practical Info

Tour Details:

- Duration: 1 day

- Start Time: 09:30 AM

- End Time: 5:00 PM

- Cost: € 995 per person excluding VAT (there are special prices for 2 or more persons)

You can book this tour by sending Peter an email with details at peterdekuster@hotmail.nl

TIMETABLE

09.40 Tea & Coffee on arrival

10.00 Morning Session

13.00 Lunch Break

14.00 Afternoon Session

17.00 Drinks

What Can I Expect?

Here’s an outline of The Hero’s Journey in Musée Rodin Paris

Journey Outline

OLD STORIES

- The Power of your Story

- Your Story is Your Life, Your Life is Your Story

- What is Your Story?

- Your Hero’s Journey

- Is It Really Your Story You Are Living?

- Old Stories (stories about you, your art, your clients, your money, your self promotion, your happiness, your health)

- Tell your current Story

YOUR NEW STORY

- The Premise of your Story. The Purpose of your Life and Art

- The words on your tombstone

- You ultimate mission, out loud

- The Seven Great Plots

- The Twelve Archetypal Heroes

- The One Great Story

- Purpose is Never Forgettable

- Questioning the Premise

- Lining up

- Flawed Alignment, Tragic Ending

- The Three Rules in Storytelling

- Write Your New Story

TURNING STORY INTO ACTION

- Turning your story into action

- Story Ritualizing

- The Storyteller and the art of story

- The Power of Your Story

- Storyboarding your creative process

- They Created and Lived Happily Ever After.

About Peter de Kuster

Peter de Kuster is the founder of The Heroine’s Journey & Hero’s Journey project, a storyteller who helps creative professionals to create careers and lives based on whatever story is most integral to their lives and careers (values, traits, skills and experiences). Peter’s approach combines in-depth storytelling and marketing expertise, and for over 20 years clients have found it effective with a wide range of creative business issues.

Peter is writer of the series The Heroine’s Journey and Hero’s Journey books, he has an MBA in Marketing, MBA in Financial Economics and graduated at university in Sociology and Communication Sciences.

The Power of Your Story

What do I mean with ‘story’? I don’t intend to offer tips on how to fine-tine the mechanics of telling stories to enhance the desired effect on listeners.

Where shall we begin? There is no beginning. Start where you arrive. Stop before what entices you. And work! You will enter little by little into the entirety. Method will be born in proportion to your interest. – Auguste Rodin

I wish to examine the most compelling story about storytelling – namely, how we tell stories about ourselves to ourselves. Indeed, the idea of ‘one’s own story’ is so powerful, so native, that I hardly consider it a metaphor, as if it is some new lens through which to look at life. Your story is your life. Your life is your story.

When stories we watch in Musée Rodin touch us, they do so because they fundamentally remind us of what is most true or possible in life – even when it is a escapist romantic story or fairy tale or myth. If you are human, then you tell yourself stories – positive ones and negative, consciously and, far more than not, subconsciously. Stories that span a single episode, or a year, or a semester, or a weekend, or a relationship, or a season, or an entire tenure on this planet.

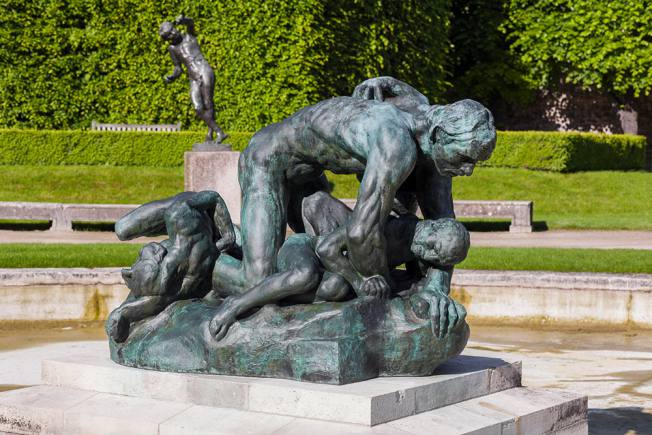

The Burghers of Calais

A powerful story in the Musée Rodin that beautifully illustrates the idea that “your story is your life, your life is your story” can be found in the history and meaning behind Rodin’s masterpiece, The Burghers of Calais. This sculpture is not just an artistic achievement but a living testament to the way stories shape perception—both personal and collective.

Rodin’s The Burghers of Calais portrays six ordinary citizens called to sacrifice themselves to save their city during the Hundred Years’ War. The emotional intensity of the piece is not simply in its depiction of historical figures, but in how the six men become conduits for themes of fear, hope, regret, expectation, and courage. Their individual reactions, as rendered by Rodin, are deeply human—they are, in essence, stories each burgher tells himself as he faces doom and duty.

This artwork demonstrates that the stories we inhabit are not confined to neat beginnings or tidy endings. There is no single “starting point”—each burgher brings his entire past, anxieties, and hopes to the moment captured in bronze. Rodin didn’t isolate one heroic narrative; rather, he revealed a tangle of personal stories that, together, create a collective legacy. The “method” of telling emerges, as Rodin suggests, from genuine engagement with the subject. As a viewer, you meet each figure where you arrive—some are bowed, lost in self-recrimination; others stand resigned or defiant—before encountering the whole, just as in life we enter our stories in medias res, often not knowing the shape they will take.

The Burghers of Calais is deeply compelling because it makes visible the process of private storytelling—each burgher must make sense of his own role and impending fate. This mirrors our own inner dialogue and narrative-making, conscious or subconscious. The sculpture’s universal impact comes from its ability to spark reflection about our own “episodes,” struggles, hopes, and legacies—reminding us that to be human is to embroider and inhabit a story, continuously, whether for a moment or a lifetime.

This work at the Musée Rodin stands as a vivid illustration that the stories we watch—and the stories we live—are inseparable, that narrative is both lens and substance. The Burghers of Calais is not just a monument of history, but an invitation to see yourself: not as an isolated character, but as someone always in the midst of a story, crafting meaning amid uncertainty, just as Rodin proposed—“method will be born in proportion to your interest.”

Stories to Navigate Our Way Through Life

Telling ourselves stories helps us navigate our way through life because they provide structure and direction. We are actually wired to tell stories. The human brain has evolved into a narrative-creating machine that takes whatever it encounters, no matter how apparently random and imposes on it ‘chronology and cause – and – effect logic’. We automatically and often unconsciously, look for an explanation of why things happen to us and ‘stuff just happens’ is no explanation.

Stories impose meaning on the chaos; they organize and give context to our sensory experiences, which otherwise might seem like no more than a fairly colorless sequence of facts. Facts are meaningless until you create a story arond them.

I invent nothing, I rediscover. – Auguste Rodin

Ugolino and his Children

Auguste Rodin’s artistic philosophy and creative process provide a profound illustration of how storytelling is a fundamental human mechanism for making sense of the world. Rodin did not merely create sculptures; he invented narratives through form that encapsulate the complexity and emotional depth of human experience. His approach aligns with the idea that humans are wired to tell stories that impose order on the chaos of life by weaving facts and sensory input into meaningful, structured narratives.

Rodin famously emphasized that unlike literary narratives, sculpture does not tell a story with a beginning, middle, and end. Instead, it captures a single moment or phase of an episode filled with emotional and psychological weight. For example, in his sculpture “Ugolin et ses enfants” (Ugolino and his Children), Rodin portrays the tragic figure of Count Ugolino from Dante’s Divine Comedy. The sculpture conveys a raw inner conflict—a moment charged with anguish, love, and despair—without relying on narrative exposition. The viewer intuitively understands the tension and meaning because Rodin has imbued the form with the essence of the story’s emotional truth. This reflects how the brain constructs narrative meaning not by sequential facts alone, but by sensing emotional and causal connections, even if implicit or partial.

The Gates of Hell

This philosophy became central to Rodin’s larger project, The Gates of Hell, inspired by Dante. Instead of a linear depiction of Dante’s narrative, Rodin created a complex, multilayered assemblage of fragmented human forms expressing a range of passions, sufferings, and tensions. The Gates resist a single fixed story; rather, they mirror how the human mind scatters sensory input and memory fragments and then imposes personal meaning—the very act of storytelling itself. The sculptures exemplify how we make sense of events, often incomplete or chaotic, by focusing on key emotional moments and letting those moments resonate to form a broader understanding.

Rodin’s art demonstrates the deep truth that stories are not neat packages but evolving processes. Like the sculptures, our life stories are composed of episodes, feelings, and memories that we interpret in different ways at different times. The shaping of narrative “method,” as Rodin suggests, is born from sustained interest, reflection, and engagement with the material of our lives. Just as Rodin’s figures appear unfinished or rough around the edges, our stories are ongoing, and meaning is continuously created and revised.

In the year 1900, Rodin shows his famous Gate of Hell. He thus reacts with a Prometheus-like humanism to Freud’s discoveries of the unconscious and of the repression of the sexual drive. with this monumental masterpiece, Rodin opens up a new cosmos for art. Its significance to sculpture can be compared to what Van Gogh, Gauguin and Cézanne meant to painting.After centuries of dormant existence, Rodin renews its radiance; he seeks connection with the Italian ‘cinquecento’. Rodin manages to take up the artistic message of the Renaissance, especially that of Michelangelo, and pass it on to future generations. Rodin himself confessed “I go way back, deep into classical antiquity. I want to reconnect the past with the modern age, bring the memory to life, form a judgment about it and finally complement both into a whole. The people are guided by symbols (archetypes, myths, stories PdK). That is very different from lies.” The truth and the greatness of man, that’s what Rodin actually strives for, for that De Helle gate – inspired by Dante’s ‘Inferno’, Ovid’s ‘Metamorphoses’ and Baudelaire’s Fleurs du Mal – forms a reservoir of forms, which only came about from ‘the will to power’ and the power of inspiration, as found in Nietzsche. Rodin is a Michelangelo if he had had the chance to hear Wagner… But he never completed this gateway, he was accused. To which the sculptor seems to have replied: “What about the cathedrals in France, are they completed?” With this irritating Gate of Hell, on which the figures rise and disappear – not so much as loving, but rather as desperate figures – Rodin puts an end in one fell swoop to the stale academicism that has dominated the plastic art for a very long time. There were forerunners like Houdon or Carpeaux who were able to give sculpture an expression of the immaterial and psychological, but Rodin added something entirely new: his ability to convey the tension of passion and confusion of feelings which he experienced himself, to express in his sculpture.

In this way, Rodin’s work exemplifies the cognitive principle that facts are inert until organized by a story. His sculptures invite viewers to intuitively construct narratives, to find connection and cause-and-effect where none is explicitly provided, mirroring the natural human tendency to search for story-based explanations of experience. By capturing intense psychological states and emotional gestures, Rodin enabled his art to act as a powerful conduit for human storytelling—making the invisible narratives of the inner life visible and palpable.

Thus, at the Musée Rodin, the story itself—how humans impose narrative meaning on life’s chaos—is embodied within the sculptures. They teach us that storytelling is not just a literary device, but a lived, fundamental process through which identity and understanding are formed. Rodin’s art is an enduring testament to the power of stories to shape how we experience ourselves and the world.

What Do I Mean with Story?

By ‘story’ I mean those tales we create and tell ourselves and others, and which form the only reality we will ever know in this life. Our stories may or may not conform to the real world. They may or may not inspire us to take hope – filled action to better our lives. They may or may not take us where we ultimately want to go. But since our destiny follows our stories, it is imperative that we do everything in our power to get our stories right.

For most of us, that means some serious editing.

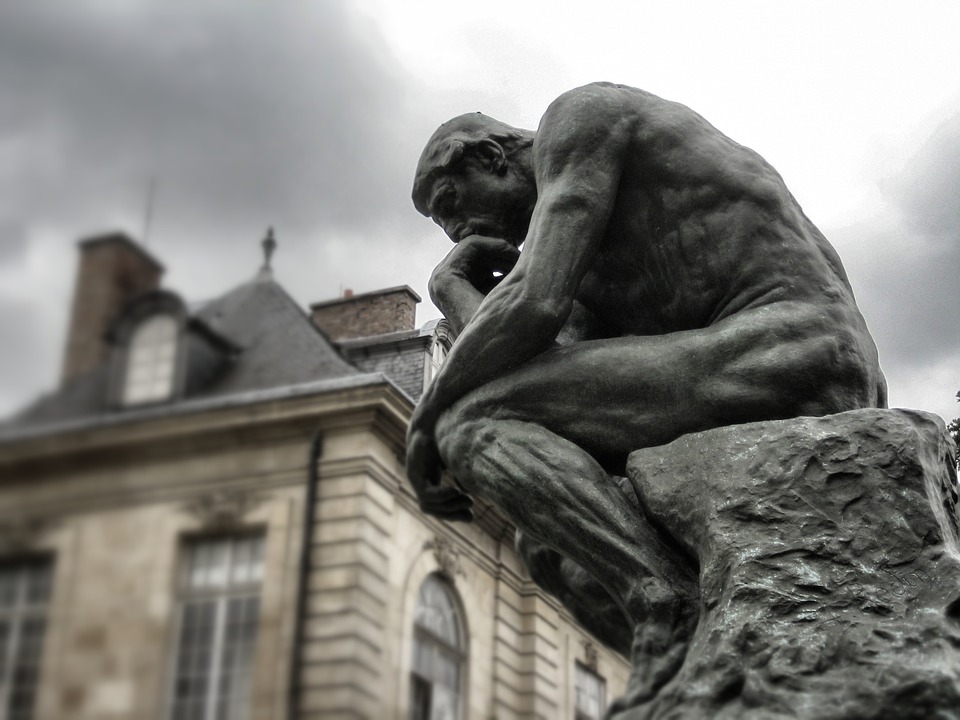

The Thinker

A compelling story in the Musée Rodin that richly embodies the idea of storytelling as a fundamental human process shaping identity and understanding is the sculpture “The Thinker.” Originally conceived as part of The Gates of Hell, The Thinker stands alone as a powerful meditation on how individuals wrestle with their inner narratives to construct meaning and destiny.

Rodin’s The Thinker captures a man deeply absorbed in contemplation, embodying the moment when one confronts the chaos of existence and strives to impose order through thought, reflection, and storytelling. The figure’s muscular tension and downward gaze evoke the intense mental activity that accompanies the creation and revision of personal stories. This sculpture resonates with the idea that we are continually authoring and editing the stories we tell ourselves—stories that may or may not align perfectly with external reality but ultimately shape how we live and who we become.

The story The Thinker tells is not static—it is a process of ongoing editing, refinement, and self-questioning. Like many individuals, the figure seems caught at a crossroads, pondering choices, consequences, and meaning. This moment reflects the imperative to “get our stories right,” recognizing that while our internal narratives are powerful engines that drive our destinies, they also require vigilance, honesty, and courage to revise and improve.

Rodin’s brilliance lies in making visible this invisible, psychological reality—that storytelling is not merely crafting fictional tales but a lived practice in which identity is continually forged. The Thinker reminds us that our stories are dynamic, often messy enterprises where hope, doubt, despair, and insight intermingle. This sculpture stands as a metaphor for the human condition: the struggle to bring clarity and purpose to experience through the stories we shape and reshape in our minds.

In the broader context of the Musée Rodin, The Thinker complements works like The Burghers of Calais and The Gates of Hell by highlighting the inner dimension of storytelling, where narrative meaning is wrestled with at a psychological level. Together, these sculptures illustrate storytelling as a holistic human act—from external communal narratives about sacrifice and fate to deeply personal internal dialogues that define who we are.

Ultimately, The Thinker offers a great story for Musée Rodin that illustrates how the lives we lead, the identities we claim, and the futures we pursue rest on the stories we tell ourselves. Rodin’s art powerfully invites viewers to engage in their own story editing—to recognize the creative and transformative potential of narrative as a fundamental human practice essential for navigating life’s chaos and realizing hope-filled action

In 1880, a petition from artists to the Ministry of Art and Culture led to “Monsieur Rodin, a sculptor, being commissioned, for a sum of 8,000 francs, to design a carved door in bas-relief for the Musée des Arts Décoratifs and should have Dante’s Divina Commedia as its theme”. In addition, the state makes a large studio available to him. Rodin immediately set to work, re-reading the Divina Commedia, filling hundreds of pages of his sketchbook, making dozens of models and tirelessly studying similar works: the doors of the Baptistry of Florence and, in particular, Ghiberti’s door, the so-called “Paradise Door”. ‘. Rodin said, “Dante is not only a seer and a writer, but also a sculptor.” Paolo and Francesca, Ugolino and various damned should be considered direct interpretations of Dante’s work. The thinker is an image of the poet himself. But soon Rodin expands the theme and adds characters who betray Baudelaire’s influence. His explicit intention is to create a universe, to realize a fresco of passions and human feelings. This gigantic task is the reservoir of forms from which Rodin will draw again and again to create with his own hands a whole series of groups of figures, all ‘individualised’; each group is a masterpiece that can claim autonomy.

Your Story is Your Life, Your Life is Your Story

To rewrite your story, you must first identify it. To do that you must answer the question: In which important areas of my life is it clear that I cannot achieve my goals with the story I have got?

Only after confronting and satisfactorily answering this question can you expect to build new reality – based stories that will take you where you want to go.

An artist worthy of the name should express all the truth of nature, not only the exterior truth, but also, and above all, the inner truth. – Auguste Rodin

Your life is the most important story you will ever tell, and you are telling it right now, whether you know it or not. From very early on you are spinning and telling multiple stories about your life, publicly and privately, stories that have a theme, a tone, a premise – whether you know it or not. Some stories are for better, some for worse. No one lacks material. Everyone’s got a story.

There are unknown forces in nature; when we give ourselves wholly to her, without reserve, she lends them to us; she shows us these forms, which our watching eyes do not see, which our intelligence does not understand or suspect. Auguste Rodin

And thank goodness. Because our capacity to tell stories is, I believe just about our profoundest gift. Perhaps the true power of the story metaphor is best captured by this seemingly contradiction: we employ the word ‘story’ to suggest both the wildest of dreams (it is just a story ……) and an unvarnished depiction of reality (okay, what is the story?). How is that for range?

The challenge? Most of us are not writers. That is what I intend to do here in this hero’s journey. First, explore with you how pervasive story is in life, your life, and second, to rewrite it.

“I have always endeavored to express the inner feelings by the mobility of the muscles. – Auguste Rodin

Story is everywhere in life. Perhaps your story is that you are responsible for the happiness and livelihoods of dozens of people around you and you are the unappreciated hero. If you are focused on one subplot – your business – then maybe your story is that you sincerely want to execute the major initiatives in your company, yet you are restricted in some essential way. Maybe your story is that you must keep chasing even though you already seem to have a lot (even too much) because the point is to get more and more of it – money, prestige, power, control, attention. Maybe your story is that you and your children just can’t connect. Or your story might be essentially a rejection of another story – and everything you do is filtered through that rejection.

“Dante is not only a visionary and a writer, he is also a sculptor. His style is lapidary in the good meaning of the word. When he describes a personage he fixes his attitude and his gestures…. I have lived a whole year with Dante living with him and by him, drawing his eight Circles of Hell” – Rodin

Story is everywhere. Your body tells a story. The smile or frown on your face, your shoulders thrust back in confidence or slumped roundly in despair, the liveliness or fatigue in your gait, the sparkle of hope and joy in your eyes or the blank stare, your fitness, the size of your gut, the tone and strength of your physical being, your overall presentation – those are all part of your story, one that’s especially apparant to everyone else. We judge books by their covers not simply because we are wired to judge quickly but because the cover so often provides astonishing accurate clues to what is going on inside. What is your story about your physical self? Does it truly work for you? Can it take you where you want to go in the short term? How about ten years from now? What about thirty?

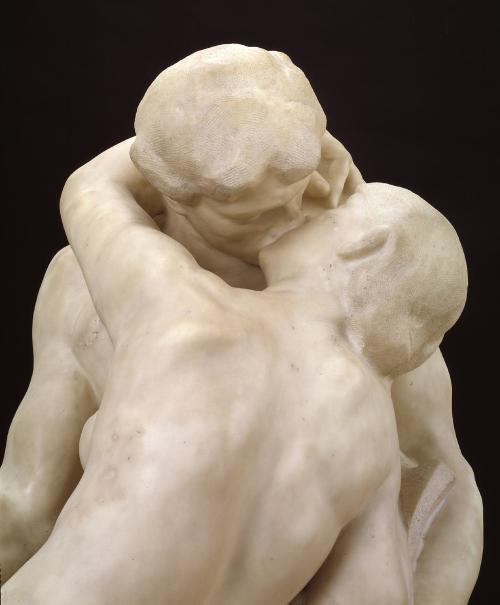

“The man’s head is bent, that of the woman is lifted, and their mouths meet in a kiss that seals the intimate union of their two beings. Through the extraordinary magic of art, this kiss, which is scarcely indicated by the meeting of their lips, is clearly visible, not only in their meditative expressions, but still more in the shiver that runs equally through both bodies, from the nape of the neck to the soles of the feet, in every fiber of the man’s back, as it bends, straightens, grows still, where everything adores—bones, muscles, nerves, flesh—in his leg, which seems to twist slowly, as if moving to brush against his lover’s leg; and in the woman’s feet, which hardly touch the ground, uplifted with her whole being as she is swept away with ardor and grace.”

Rodin revealed human love and life as a process of mutual creation between women and men. Passion is not only a union with those we desire and adore, but also an elevation through shared feelings and sensuality which is always in process, never complete. His representations of the fragility of our mutual creation were as inchoate, vulnerable yet compelling as the material shapes that seemed to emerge only part-finished from the bronze or blocks of stone. Gustave Geffroy

You have a story about your company, though your version may depart wildly from your customer’s or business partners. You have a story about your family. Anthing that consumes our energy can be a story, even if we don’t always call it a story. There is the story of your relationship. The story of you and food, or you and anger, or you and impossible dreams. The story of you, the friend. The story of you, your father’s son or your mother’s daughter. Some of these stories work and some of them fail. According to my experience, an astounding number of these stories, once they are identified are deemed tragic – not by me, mind you but by the people living them.

Like it or not, there will be a story around your death. What will it be? Will you die a senseless death? Perhaps you drank too much and failed to buckle your seat belt and were thrown from your car, or you died from colon cancer because you refused to undergo an embarrassing colonoscopy years before when the disease was treatable. Or after years of bad nutrition, no exercise, and abuse of your body, you suffered a fatal heart attack at age fifty – nine. ‘Senseless death’ means that it did not have to happen when it happened; it means your story did not have to end the way it ended. Think about the effect the story of your senseless death might have on your family, on those you care about who you are leaving behind. How would that story impact their life stories? Ask yourself, Am I okay dying a senseless death? Your immediate reaction is almost certainly, “No!, of course not!

Unhealthy storytelling is characterized by a diet of faulty thinking and, ultimately, long – term negative consequences. This undetectable, yet inexorable progression is not unlike what happens to coronary arteries from a high-fat, high-cholesterol diet. In the body, the consequence of such a diet is hardening of the arteries. In the mind, the consequence of bad storytelling is hardening of the categories, narrowing of the possibilities, calcification of perception. Both roads lead to tragedy, often quietly.

The cumulative effect of our damaging stories will have tragic consequences on our health, engagement, performance and happiness. Because we can’t confirm the damage our defective storytelling is wreaking, we disregard it, or veto our gut reactions to make a change. Then one day we awaken to the reality that we have become cynical, negative, angry. That is now who we are. Though we never quite saw it coming, that is now our true story.

We enjoy the privilege of being the hero, the final author of the story we write with our life, yet we possess a marvelous capacity to give ourselves only a supporting role in the ‘storytelling’ process, while ascribing the premier, dominant role to the markets, our family, our kids, fate, chance, genetics. Getting our stories straight in life does not happen without our understanding that the most precious resource that we human beings possess is our energy.

It is our storytelling that drives the way we gather and spend our energy. Stories determine our personal and professional destinies. And the most important story you will ever tell about yourself is the story you tell to yourself.

So, you would better examine your story, especially this one that is supposedly the most familiar of all. Participate in your story rather than observing it from afar, make sure it is a story that compels you. Tell yourself the right story – the rightness of which only you can really determine, only you can really feel – and the dynamics of your energy change. If you are finally living the story you want, then it need not – it should not and won’t – be an ordinary one. It can and will be extraordinary. After all you are not just the author of your story but also its main character the hero. Heroes are never ordinary.

In the end your story is not a tragedy. Nor is it a comedy or a romance or a thriller or a drama. It is something else. What label would you give the story of your life, the most important story you will ever tell. To me that sounds like a hero’s journey.

End of story.

What Is Your Story?

In 1883 Rodin was commissioned by the Societé des Gens de Lettres to create a monument in honor of the novelist Honoré de Balzac (1799 – 1850): the Monument to Balzac, in Rodin’s work, marks the beginning of twentieth-century sculpture with a new sculptural language. Balzac is definitely ahead of his time and Rodin thus opens the way to completely new expression possibilities for sculpture. First, the image is no longer a slavish imitation of reality. Furthermore, it very daringly simplifies the forms. Rodin says of this: “Nothing I have made so far has satisfied me so much, for nothing has cost me so far, nothing so depicts so intimately the quintessence of what I consider to be the secret law of my art.” Photographs, facial features, the dressing gown, nude studies, sketches… everything contributes to this gigantic work, of which Rodin finally produces the final version. Balzac in overcoat. More than ever before, Rodin’s great desire was to express not so much the physical aspect of the writer as his personality in its essence.The reactions are eloquent and biting: ‘coalsack, penguin, shapeless larva, fetus.. The Societé des Gens de Lettres rejects the statue, although some prominent contemporaries protest, including Monet, Toulouse-Lautrec, Signac, Débussy and Clémenceau. Rodin trusts his genius: he buys back the statue and puts it in Meulon, waiting for better times.

With relatively few variations, heroes and heroines tell stories about basically five major subjects.

- Business

- Family

- Health

- Friendships

- Happiness

By asking yourself basic questions about how you feel about what you do and how you conduct yourself – and by trying honestly to answer them, of course – you begin to identify the dynamics of your story.

Your Story around your Business

You have a story to tell about your passion for your work and what it means for you. And because more than half our waking life is consumed by working at your business, how we frame this story is critical to our chance for passion and happiness.

One can find errors in my Balzac; the artist does not always attain his dream; but I believe in the truth of my principle; and Balzac, rejected or not, is nonetheless in the line of demarcation between commercial sculpture and the art of sculpture that we no longer have in Europe. My principle is to imitate not only form but also life. I search in nature for this life and amplify it by exaggerating the hollows and lumps, to gain thereby more light, after which I search for a synthesis of the whole… I am now to old to defend my art, which has sincerity as its defense. Auguste Rodin

How do you characterize your relationship to your work? Is it a burden or a joy? Deep fulfillment or an addiction? What compels you to get up every day and go to work? The money? Is the driving force increased prestige, power, social status? A sense of intrinsic fulfillment? The contribution you are making? Is it an end in itself or a means to something else? Do you feel forced to work or called to work? Are you completely engaged at work? How much of your talent and skill are fully ignited?

What is the dominant tone of your story – inspired? challenged? disappointed? trapped? overwhelmed?

Does the story you currently tell about work take you where you want to go in life? If your story about work is not working, what story do you tell yourself to justify it, especially given the tens of thousands of hours it consumes?

Suppose you did not need the money: Would you continue to go to work every day? Write down five things about working at your business that, if money were no issue, you would like to continue.

Your Story Around Family

What is your story about your family life? In the grand scheme, how important is family to you? So … is your current story about family working? Is the relationship with your husband, wife, or significant other where you want it to be? Is it even close to where you want it to be? Or is there an unbridgeable gap between the level of intimacy, connection and intensity you feel with him or her and the level you would like to experience?

Is your story with your children working? How about your parents? Your sibblings? Other family members?

If you continue on your same path, what is the relationship you are likely to have, years from now with each of your family members? If your story is not working with one or more key individuals, then what is the story you tell yourself to allow this pattern to persist? To what extent do you blame your business for keeping you from fully engaging with your family? (really?) Your business is the reason you are disengaged from the most important thing in your life, the people who matter most to you? How does that happen? According to your current story, is it even possible to be fully engaged at work and also with your family?

Your Story Around Health

What is your story about your health? What kind of job have you done taking care of yourself? What value do you place on your health, and why? If you continue on your same path, then what will be the likely health consequences? If you are not fully engaged with your health, then what is the story you tell yourself and others – particularly your spouse, your kids, your doctor, your colleagues and anyone who might look up to you – that allows you to persist in this way? If suddenly you awoke to the reality that your health was gone, what would be the consequences for you and all those you care about? How would you feel if the end of your story was dominated by one fact – that you had needlessly died young?

Do you consider your health just one of several important stories about yourself but hardly toward the top? Does it crack the top three? top five? If you have been overweight, or consistently putting on weight the last several years; if you smoke; if you eat poorly; if you rest infrequently and never deeply; if you rarely, if ever, exercise; what is the story you tell yourself that explains how you deal, or don’t deal, with these issues? Is it a story with a rhyme or reason? Do you believe that spending time exercising or otherwise taking care of yourself, particularly during the workday, sets a negative example for others?

Given your physical being and the way you present yourself, do you think the story you are telling is the same one that others are hearing? Could it be vastly different, when seen through their eyes?

Your Story about Friends

What is your story about friendship? According to your story, how important are friends? How fully engaged are your with them? (that is don’t calculate in your mind simply how often you see them but what you do and how you are when you’re together). If close friendships are important to you, yet they are clearly not happening in your life, what is the story you tell yourself that obstructs this from happening?

To what extent are friendships important to your realizing what you need and want from life? If you have few or no friends, why is that? Is this a relatively recent development – that is, something that happened since you got married for example, or had a family, or got more consumed by work, or got promoted, or got divorced, or experienced a significant loss, or moved away from your hometown?

When you think of your closest friendships over the last five years, can you say any of them has grown and deepened? People who have a best friend at work are seven times more likely to be engaged in their work, get more done in less time, have fewer accidents and are more likely to innovate and share new ideas.

Suppose you had no friends – what would that be like? This may seem like a morbid exercise but write down three ways in which being completely friendless might make your life poorer (no one to turn to in times of crisis and celeb

Your Hero’s Journey

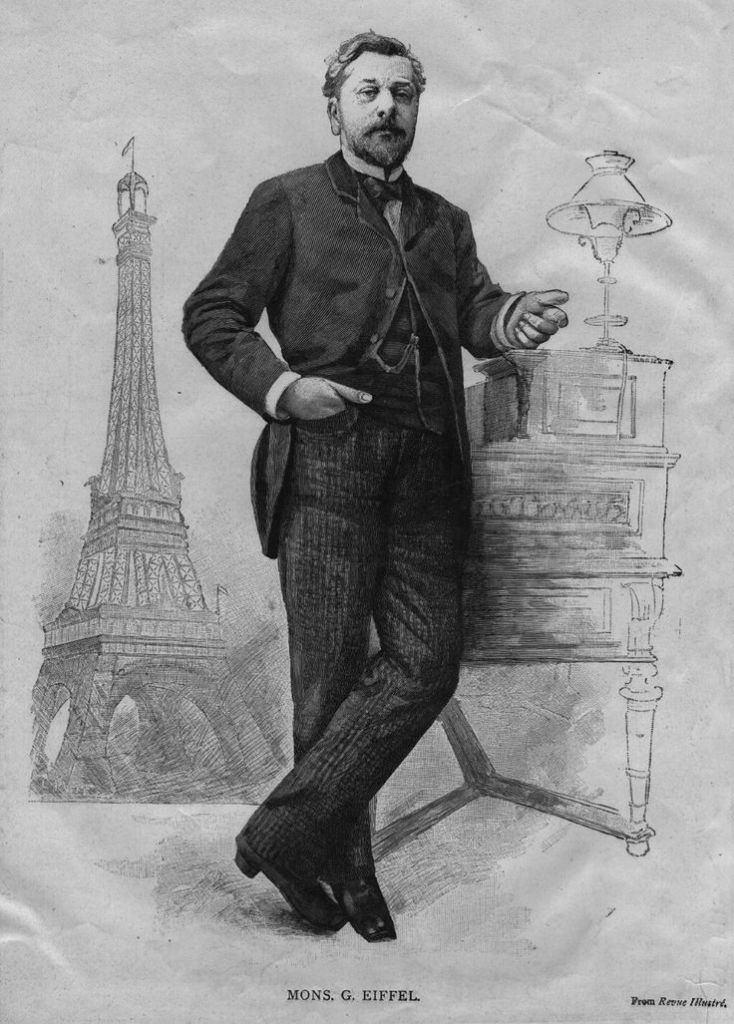

I ought to be jealous of the tower. She is more famous than I am. – Gustave Eiffel

Who has a why to live, can bear with almost any how.

When you have a great passion, it dramatically changes your willingness to spend energy and take risk. When the stakes are a large sum of money people don’t take great risks. When the stakes are love and life and that which has incalculable value, people go the extra mile.

A great passion is the epicenter of everyone’s hero’s journey story. Passion is one of the three foundations of good storytelling

Without passion, no character in a book, or movie or in art would do anything interesting, meaningful, memorable, worthwhile. Without passion, our hero’s journey story has no meaning. It has no coherence, no direction, no inexorable momentum. Without passion, our life still ‘moves’ along – whatever that means, but it lacks an organizing principle. Without passion, it is all but impossible to be fully engaged. To be extraordinary.

With passion, on the other hand, people do amazing things: good, smart, productive things, often heroic things, unprecedented things. Passion is the thing in your hero’s journey you will fight for. It is the ground you will defend at any cost. Passion is not the same as ‘incentive’, but rather the motor behind it, the end that drives why you have energy for some things and not for others.

There is an attraction and a charm inherent in the colossal that is not subject to ordinary theories of art … The tower will be the tallest edifice ever raised by man. Will it therefore be imposing in its own way? – Gustave Eiffel

I have seen many seen articulate their passion to themselves and to others. But articulation is not nearly enough; in fact it is really not even worth of a pat on the back, so long as one continues to live one’s life in a way that does very little, if anything, to support that passion. Indeed, to say you have a passion and then to do nothing about it is, first, a sham, and, last, a tragedy.

Most people who have been living in this way, when inspired to be passionate, will quickly identify what they claim to be their true passion in life.

To find one’s true passion sometimes takes work. Fortunately, the skill it requires is one that every person is blessed with.

For a few people, naming one’s passion comes with remarkable ease. The individual feels it in the deepest part of his or her soul; the passion has always been there, even if it got lost for a very long while, remaining unexpressed to oneself and to those who are the objects of one’s passion. Deep enduring passion is virtually always motivated by a desire for the well-being of others.

You know passion when you see it.

To author a workable, fulfilling new story, you will need to ask yourself many questions and then answer them, none more important than those that concern passion. Passion is the sail on the boat, the yeast in the bread. Once you know your passion – that is, what matters – then everything else can fall into place. Getting your passion clear is your defining truth. What is the passion of your life? Whatever it is, it had better be someting for which you will move mountains, cross deserts, seven days a week, no questions asked.

It seems to me that it had no other rationale than to show that we are not simply the country of entertainers, but also that of engineers and builders called from across the world to build bridges, viaducts, stations and major monuments of modern industry, the Eiffel Tower deserves to be treated with consideration. – Gustave Eiffel

Once you find your passion, you have a chance to live a story that moves you and those around you. A story that make them live happily ever after.

Is It Really Your Story You Are Living?

My dear Mama, you are definitely the hen who hatched a famous duck. Henri Toulouse Lautrec

The manipulations of our story are numerous, often impossible to recognize or calibrate, and by no means always or wholly destructive. But because outside influences have the capacity to exercise profound, at times paralyzing, sway over us and how we live our days, it is imperative – at least for the vast majority of us who have ever felt a ‘misalignment’ in our lives, a gnawing lack of engagement and joy – that we work out figuring out how we ended up doing what we do and being who we are.

The cafes bore me; going downstairs is a nuisance. Painting and sleeping – that’s all there is. Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec

We wake up one morning and feel rotten, not knowing it because we have become so dogmatic and our story so inflexible, that we are impervious to change and even fresh input. Unaware that every important decision in our life has been triggered by one goal: the avoidance of pain and risk, professionally and personally.

Is there someone out there to call you out on the phony, self – sabotaging parts of your story? Do you have someone who cares enough to do that, and is himself or herself unentangled? Who sees you and the world with some measure of objectivity? Whom you trust and respect? If you have such a person or persons, that is good. Great, in fact. But een if you do, you don’t want to rely on others to police yourself.

Tragedies happen when we don’t examine our story to see if it is really ours anymore, when we don’t look hard to see if perhaps someone or something else has infiltrated it without our conscious knowledge or consent. If you don’t activate your build in storyteller if you don’t start listening to your intuition, ou make your evolving story vulnerable to hijacking, to rerouting, to programming.

I have tried to do what is true and not ideal. Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec

That is why it is vital to waken ourselves to the brilliant, subtle methods that individuals and institutions use to indoctrinate us.Of course, doing what I am suggesting – unerringly knowing what is good for you versus what is bad for you – is anything but easy. The answer ‘it is my story and I’m sticking to it’ speaks to this difficulty. It suggests two things simultaneously. First: my story is an unchangeable story, and second, my story may well be wrong but I will never abandon it so long as it is mine. There is honor simply in clinging to the ‘mine -ness’ of it; better to propagate a false illusion one can call one’s own than rent out a truth belonging to someone else.

The Private Voice

The hero’s journey is all about the efforts of the great storytellers to reveal the one great universal story of mankind. The quest for the universal story climaxes in the 19th century with the effort to capture the elusive moment. The power of the story in stone enticed the builders of Stonehenge, the Pyramids and the Parthenon. But it was the power of the story in light that produced the most modern art forms, for light, the nearly instaneous messages of sensation, is the speediest, the most transient. Light has played surprising new roles in modern times for those who would re-create the world with their stories.

“Modernity,” said Baudelaire, “is the transitory, the fugitive, the contingent, one half of art of which the other half is the eternal and the immutable.” For this modern half, light is the vehicle and the resource. It was the Impressionists who made an art of the instantaneous, and Claude Monet (1840 – 1926) who showed how it could be done. To shift the artist’s focus from enduring shapes to the evanescent moments required courage. It demanded a willingness to brave the jeers of the fashionable salons, a readiness to work speedily anywhere and an openness to the endless untamed possibibilities of the visual world. Cézanne summed it up when he said: ‘Monet is only an eye, but my God what an eye!’

When you focus in the moment, in the instaneous – as the Impressionists did – you will hear your private voice. What does this voice tell you? Is your private voice yours? Are you sure about that? To help determine this, and whether your private voice is working for or against you, here are a few questions to ask yourself:

- What is the general tone of your inner voice? Harsh, bitter and critical? Or supportive, kind and encouraging?

- Estimate how much of the time your inner voice is a constructive force in your life, and how much a destructive one. To what extent does it instill you with confidence and hope? To what extent does it terrorize you with stories of inadequacy, incompetence and regret?

- Ever feel that your inner voice is not really you speaking? If it does not feel like you, whose voice might it be? Consider both content and tone.

- To help you achieve real happiness and to leave the legacy you desire for those you care about most, what changes would you make in the content and tone of your private voice?

- To what extent is your private voice aligned with your ultimate mission in life? What seems to be the driving force behind your private voice? Where is it taking you?

The seven years of service that appalled so many were full of attraction to me. A friend who was in a regiment of the Chasseurs d’Afrique and who adored military life, had communicated to me his enthusiasm and inspired me with his love for adventure. Nothing attracted me so much as the endless cavalcades under the burning sun, the razzias, the crackling of gunpowder, the sabre thrusts, the nights in the desert under a tent, and I replied to my father’s ultimatum with a superb gesture of indifference….. I succeeded, by personal insistence, in being drafted into an African regiment. In Algeria I spent two really charming years. I incessantly saw something new; in my moments of leisure I attempted to render what I saw. You cannot imagine to what an extent I increased my knowledge, and how much my vision gained thereby. I did not quite realize it at first. The impressions of light and color that I received there ware not to classify themselves until later; they contained the germ of my future researches. – Monet

The stories we tell and hear embed themselves more deeply in our subconsciousness the more they are repeated.

“I am grinding away, sticking to a series of different effects, but the sun sets so early at this time that I can’t go on…. I’m becoming so slow in working as to drive me to despair, but the more I go on, the more I see that I must work a lot to succeed in rendering what I am looking for: “Instantaneity,” especially the evelope, the same light spread everywhere, and more than ever I am disgusted by easy things that come without effort.” Monet

In the end though, it is only the one voice that truly matters. Because your inner voice is telling you your story all the time, you are rarely even conscious that you have been telling a story. Indeed it is hard to imagine what it would feel like if suddenly you stopped telling yourself your story, or even just changed this one

The Three Rules of Storytelling

Purpose, truth, action.

When writers really want to emphasize something, they put it in a one sentence paragraph. If they suspect even that is not emphasis enough, then they go to Plan B: break things up into still more melodramatic, one-word paragraphs.

Purpose.

Truth.

Action.

All good storytelling coheres around those three ideas. They are the three criteria, taken together, by which we judge the workability and ultimate success of our story. With those three principles in your pocket, you can summon your best story to live. You are virtually guaranteed to keep your story vital, moving, productive, fulfilling.

Let us review them:

Purpose

What is my ultimate purpose? What am I living for? What principle, what goal, what end? For my whole life, and every single day? Why do I do what I do? For what? What is the thing that would get me to be fully engaged, and to be sure and at peace that it is the right decision, the necessary one, the only one? What is the thing I am driving toward – or should be – with every action I take? Have I articulated to myself my deepest values and beliefs, which are the bedrock of who I am and which must be inextricably tied to my purpose (and vice versa)? Who do I want to be at the end? What legacy do I want to leave? What epitath about myself could ‘I live with’? When all is said is done, how do I want to be remembered? What is non- negotiable in my life? What do I believe must happen for me to have lived a successful life? Is my story taking me where I want to go? Is it “on – purpose”? Consistently? And why am I telling this story? What is the real motive? Is my purpose noble or ignoble?

Truth

Is the story I am telling true? Does it conform to known facts? Is it grounded in objective reality as fully as possible; that is, does it coincide with some generally agreed-upon portrayal of the world? Or is it true only if I’m living in a dreamland? Is it a lie I tell myself when I think, ‘This is the way the world is’ – my own, probably biased evaluation of things, one that is dubiously defensible, and which I repeat to myself because it provides false comfort for the way my life has turned out? Do I sidestep the parts of my story that are obviously untrue because they are just too painful to confront? Is my story I still believe when I really dig down, when I listen to my most candid, private voice, when I do my best to shut out other influences and hear instead what I genuinely think and feel? Which is the truer statement: My story is honest and authentic or My story is made up? Is my story closer to a documentary or a work of fantasy? What myths am I perpetuating that could potentially steal my fate in areas of my life that really matter?

Action

A good story is premised on action … is it mine? With my purpose firmly in mind, along with a confidence about what is really true, what actions will I now take to make things better, so that my ultimate purpose and my day-to-day life are better aligned? What habits do I need to eliminate? What new ones do I need to breed? Is more of my life spent participating or observing? Are my actions filled with hope – hope that I will succeed, hope that the change I seek is realistically within my grasp? Or is my ‘action-taking’ really more accurately portrayed as ‘going through the motions’? Do I believe to my core that, in the end, my willingness to follow through with action will determine the success of my life? Do I believe that if I act with commitment and consistency I will end up where I want to be, where I have always felt I am capable of being? Does the story I tell myself move me to action? Does it inspire hope and determination in me? Am I confident that I can make any necessary course correction, no matter what stage of life I am in, no matter how many times I may have failed at it in the past? Do I proceed in the belief that I will never surrender in this effort because my happiness and success as a human being is what is at stake?

One must hold one’s story up as if against a three – part checklist: your story must have purpose (can you name it?), your story must be true (is it?), your story must lead to hope-filled action (does it?).

When a hero achieves a breakthrough, it is always – always – because he or she has come to a fundamental understanding of the interlocked nature of all three rules of storytelling. It is nog good enough to satisfy one or even two of the three rules and content yourself that your story has now improved; it will not leave you 33% better off or 67% better off. More likely, you may have fulfilled one or even two of the three rules but because all three rules are not followed, your story remains dysfunctional.

While one needs to understand deeply each of the three rules of storytelling, not all rules are created equally. Truth and action probably give people more trouble than purpose. For example, what about those people who have purpose nailed…. but not action? This is probably the most common of the permutations, and in some ways the most tragic. In this group you find the novelists who have yet to set pen to paper, lovers who are single and celibate, entrepreneurs who don’t know the first thing about how to attract customers.

They Lived Happily Ever After?

If all you had to give was your total energy, you could accomplish historic things.

What gets you to focus with the highest level of commitment, of reverence for the moment? Is there something or someone in your life so sacred that nothing and no one – not ringing phones, not errands, not games in progress, not thoughts always running through your head, not money or business concerns, not insignificant noises or images whizzing by – could possibly break your concentration?

When I write about the Hero’s Journey or talk about the Hero’s Journey somewhere in the world as a travel guide, I mean listening, seeing and feeling with full force, experiencing with full force. Yet that is a kind of focus we so rarely give to things now. Why is that? What is the story we tell ourselves that prevents this from happening? Is our lack of full engagement just a stage in our life that will pass someday? Or has it always been like this? Is our story that multitasking is necessary as never before? Hey, time is money. Time is shipping away. We are not getting any younger. Anyway, is our somewhat dilluted attention really all that big a deal. Are we really losing that much by nog engaging fully?

Absolutely. Because it is not about time. It never was and never is.

It is about passion.

Every year I see entrepreneurs buy into this story – that it is about passion, not time – in the hope that it will increase performance, productivity and happiness.

Here is the dirty secret, though: The difference in depth between full engagement and multi- tasking is not incremental. It is binary. Either you are fully engaged. Or you are not. It is really that simple, yet we tell ourselves it is otherwise to keep the painful truth at bay. If a tennis pro preparing to return a 140-mph serve has two thoughts going and one of them does not have to do with returning that serve, do you know what his chances are of returning it well? I do. ZERO. Not 10%, not 5%. The same goes for writing a great story, hitting a golf ball, or doing push – ups the right way or enjoying a glass of wine, or reading a good book.

A distracted hero or heroine will not produce anything of real worth. An entrepreneur with scattered thoughts will not come up with new solutions superior to the competition’s. Indeed, multi-taskers are fortunate even to rise to a modicum of competence. Can’t you always tell when you are on the phone with someone who is simultaneously watching TV or answering e-mail? Does your interaction with that person ever come within a thousand miles of what you would call a satisfying conversation?

Multi-tasking is the enemy of extraordinariness. Human beings can focus fully on only one thing at a time. When entrepreneurs multi task, they are not fully engaged in anything, and partially disengaged in everything. The potential for profoundly positive impact is compromised. Multi – tasking would be okay – is okay – at certain times – but very few people seem to know when that time is. If you must, then multi task when it does not matter. Fully engage when it does.

They Lived Happily Ever After

How do you live happily ever after?

I identify the three things I want to get finished that day – never more than three. At the end of my day I use my 10 – 6 – 1 scale to rate myself. Now I am giving myself 10’s all the time. I found that I actually got more accomplished more completed – and at a higher level – than when I was doing lots of things. I stopped multitasking at meetings and suddenly they became shorter, crisper. The effectiveness of conversations improved threefold. Plus, it has been more enjoyable.

Learning to invest your full and best energy in whatever you are doing at that moment in full engagement is what I call The Hero’s Journey. A story i have developed over more than two decades, which posits at its core that life is enriched, flow occurs, happiness is felt because of the commitment, passion, and focus we give it, not the time we give it. These fully – engaged – in the present moments – I call ‘Moments of Bliss’ – created me more ‘Moments of Bliss’ and ‘Days of Bliss’ in two weeks than I had in the five years before, or than I probably would have in the next five years had my life and business continued the way it was going.

One of the exciting discoveries I have made is the almost perfect correlation between engagement, on one hand, and happiness, on the other. Engagement is an acquired skill that allows us to be in the present; it is where people feel happiest. (The happiness we feel about an upcoming event is really not future-oriented, but rather present-oriented happiness in the anticipation). The more engaged we are in something, the more alive we tend to feel; the more alive we feel, the happier we feel. Becoming fully engaged in our hero’s journey that deeply matters brings a rich sense of meaning, depth and dimension to our lives. Disengagement as the opposite, tragic effect. It pulls us from the core of life – characterized by intensity, passion and meaning – to its boundaries, characterized by safety, protection and disassociation.

By being engaged we experience true happiness and joy in our lives. We ignite our talents and skills.

Do You Have the Resources To Live Your Best Story

Without proper exercise, nutrition and rest, the body slowly begins to break. You are operating at a perpetual deficit. You are always exhausted. You are seriously disengaged. Your body is now in survival mode. Your stories change. To rationalize how and why this happened requires that, at some fork in the road, smart people must become suddenly stupid; pragmatics, illogical; straightshooters. There are other, totally defensible stories that bring us to this overtaxed point of course – lots of responsibility, good intentions, aging, ambition, sudden change in circumstance – but they are almost never the whole of the story.

You tell yourself things you cannot possibly believe. In an impoverished physical condition, how can you hope to live a good story? How can you hope to have the energy even to figure out what that story is?

Our physical state influences the stories we tell

Do you think the story you tell changes if one or more of the following conditions is true?

- You are tired or fatigued

- You have low blood sugar

- You have a headache

- You are ill

- You are in pain

Of course it does! When your physical story changes as by a sudden drop in blood sugar – then your whole story changes.

Many of us know that losing weight on a traditional diet is terribly difficult. One reason for this is that the story most people are telling themselves – lose weight and look better – is frankly not exactly a narrative for the ages. As a life goal for far too many people the objective of losing twenty or forty or even one hundred pounds simply to look better is just not compelling enough. Many who fail at losing weight that way have lost it when their motivation changes to something more urgent, powerful and transcendent – lose weight to be around for your grandchildren; lose weight so you will not be wheel-chair bound the last portion of your life; lose weight to improve your changes of making great journeys in world cities :). By finding motivation from a higher, passionate source or mission, you can affect your physical energy too.

The body we start out with is capable of wonderful things. But if we wish to achieve something truly extraordinary in our lives – be it athletic, intellectual, social, artistic, professional – we must build on this ‘standard – edition’ body and invest it with extraordinary energy.

Indoctrinate Yourself

“Give me two hours a day of activity and I’ll take the other twenty two in dreams” – Salvador Dali

Indoctrinate Yourself

In the Salvador Dali Museum on Montmartre Paris as part of the Hero’s Journey in Paris: The Power of Your Story we can witness the power of self-indoctrination with the story you tell yourself about yourself. Salvador Dali’s self-confident story was well-known.

Only 5 % or less of the mind should be classified as the ‘conscious story’ – controlled by self – regulatory, willful acts – while an astonishing 95% is non-conscious, automatic, instinctive.

Residing in your subconscious is most of the hidden matter that influences our stories – all the instinctual urges coded in genes (governing autonomic responses like fight-or-flight, for example), all the conditioning that took place during childhood, all the indoctrination that has occurred since the first day of life. All the conflicts and challenges beneath the surface, waging a constant battle between our wants and needs.

“At the age of six, I wanted to be a cook. At seven I wanted to be Napoleon. And my ambition has been growing steadily ever since.” Salvador Dali autobiography, The Secret Life of Salvador Dalí, “

It is this subconscious story that is hardest to retrieve and bring to the surface, to full awareness. Yet it is the mortar that goes a very long way in determining who we are and the shape our life story has taken.

Many people find it hard to accept that our lives are ruled by habitual stories rather than moment – to – moment acts of conscious stories. They don’t want to acknowledge that our stories might actually be so profoundly influenced by factors outside our normal state of awareness. After all, once we acknowledge the extent to which our behavior is governed by subconscious forces, how daunting is it to exercise full responsibility (whatever the means) for our life when but a paltry 5% of that life is really under control?

Salvador Dalí spent much of his life promoting himself and shocking the world. He relished courting the masses, and he was probably better known than any other 20th-century painter, including even fellow Spaniard Pablo Picasso. Diffidence was not in his vocabulary. “Compared to Velázquez, I am nothing,” he said in 1960, “but compared to contemporary painters, I am the most big genius of modern time.” Salvador Dali

Rather than being troubled by the percentages, and the perception that they may give rise to, I see them as a glorious challenge. Forget that so much, percentage-wise, of what we do is out of control. The part that does matters – the part that makes the real difference – is the part that we control. It is this capacity that separates us from all other life forms. This evolutionary masterpiece is the only hope we have for making course corrections in our life story.

Critic Robert Hughes described Dali’s lover Gala in his Guardian article as a “very nasty and very extravagant harpy.” But Dalí was completely dependent on her. (The couple would marry in 1934.) “Without Gala, Divine Dalí would be insane.”- – Salvador Dali

The evolution of the human species has, despite frequent missteps, moved progressively towards greater self awareness. The more self aware we are , the greater our capacity for conscious, deliberate storytelling, for creating new stories – the better able we are to change directions, to adapt, to survive and thrive. While consciousness may represent a mere 5% of our complete story, the influence this fraction exercises in the whole story of our life is far profounder than that.

“Every morning upon awakening, I experience a supreme pleasure: that of being Salvador Dalí, and I ask myself, wonderstruck, what prodigious thing will he do today, this Salvador Dalí.” – Salvador Dali

It is our conscious 5% that allows us to make story corrections to the future, especially when the 95% has taken us off a desirable course. The conscious 5% is unquestionably the most important portion inside us. It is, in fact, what truly separates us from all other species. It is what creates the possibility for self – directed change.

“A true artist is not the one who is inspired, one who inspires others – Salvador Dali

The more aware we are of hidden needs, conflicts and past dilemma’s, the better chance we have of crafting stories that meet the three criteria of storytelling (purpose, truth, hope-filled action). Once a memory of an important event or happening can be brought into your conscious story you can start to explore how that past material might be affecting your current story.

The Story Effect

If our Hero’s Journey story is your ultimate life mission, then your Action Story are the actions you take to fulfill the aims set forth in your Hero’s Journey story. They are your concrete measurables, evidence that you are acting on your story.

Inevitably, there are many changes you wish to make to turn your life into the story you want it to tell. It would be nice to think that all these changes could be made in one enthusiastic burst of self-transformation. But that does not happen. Pick a few changes and just make sure that each is:

- Important enough to you

- Realistally fixable

- Clearly defined

- Supportable by behavioral changes (rituals) that will do the trick

There is a training effect for stories. With each repetition of a story you tell yourself, that story travels your neural pathways more easily. Tell yourself that story again and again and again and soon enough pathways that were once unpaved roads, metaphorically speaking, have now become slick six – lane superhighways. Gradually repetition reinforces the primacy and value of that story – not to mention pushing away or ignoring alternative stories undeserving of your energy, which then atrophy or die, and the pathways they once traveled now narrow again, growing less supple with disuse. You become indoctrinated by your current story. You are training yourself to believe it and to live it.

Every story we tell has some effect. Stories move the needle every time we tell them. Because of this powerful story effect it is imperative that the story you tell be a constructive, not destructive one. The effect of training makes it hard to break the bonds that form. It is crucial then, to be utterly conscious about who you are and what you are doing with your life – in other words, to be brutally truthful with yourself about your purpose – so that you are aware of your story and can assess whether and how it is helping or hurting you.

There is a problem , though. You may be thoroughly well – intentioned about examining your story, yet often it is difficult, if not impossible, to see the immediate consequences of your story on yourself or others. Your story’s impact may not reveal itself for years.

Now that you are familiar with the major concepts from our The Hero’s Journey program – how our stories are our destinies; how everything we do, with or without our conscious knowledge, helps to shape our stories; how stories either take us where we want to go or they don’t; and the three fundamental criteria of all good storytelling.

Here is your Hero’s Journey towards a new story in six steps:

- The most important story you will ever tell is your own life story

- The center of your life story is PASSION.

Step 1. Identify PASSION (Ultimate Quest)

Questions to help in the process:

- What makes you happy every day?

- What makes your life really worth living?

- In what areas of your life must you truly be extraordinary to fulfill your destiny

- How do you want to be remembered?

- What is the legacy you most want to leave for others?

- What is worth dying for?

Step 2. Facing the Truth.

Here you must identify and confront your dysfunctional current stories. Some questions to get you going:

- In which of the following areas of your life is your story not working? If your behavior is not aligned with your core passion, then this story cannot take you where you want to go.

- In which areas do you need or want to be more engaged to fulfill your Ultimate Quest?

Step 3. Select a Story to Work on First

Because almost all of the core stories in our lives need at least some editing, here are some questions to help you with the selection process.

- Which of your stories causes you the most concern and grief?

- Which of your stories causes the most disruption in your life?

- Which of your stories creates the greatest misalignment with your ultime quest in life?

- Which of these stories would you most like to work on right now?

The story you have chosen to edit is your first Hero’s Quest. If you are to enjoy genuine transformation, then you must commit to work on this story for the next ninety days.

Step 4. Write the story you have been telling yourself that has allowed the misalignment to occur.

This means including the faulty thinking and strange logic that helped to form the story you now wish to edit. Write in as much detail and with as much specificity as you can. Your task is to unearth completely your current dysfunctional story.

& In what way(s) does the story yourself allow you to ignore that it is not taking you where you ultimately want to go in life – is not on passion?

& What logic do you use in the story to justify that your story does not reflect the truth?

& In what way(s) does the story not inspire you to take action to make this part of your life better?

Before you finish your Old Story, take a few dives into your subconscious world. Ask yourself these questions:

- What hidden influences might be behind some of your faulty thinking and beliefs that helped to create your current story?

- Do you get very defensive about your faulty story? If you do, then what are you protecting? Specifically, in what parts of this story are you most fragile and vulnerable? What are you most afraid of here? If you follow the fear, where does it take you?

- The story you currently tell yourself that you wish to edit clearly has not inspired you to make a change. What is the logic and rationale you have used to keep this faulty story alive in your life for so long?

- Is this really your story you are telling or someone else’s? Whose voice is it?

Step 5. Write a New Story

Write a new story that

- Is fully aligned with your ultimate quest and your passion

- Reflects the truth

- Inspires you to take hope – filled action

To help you articulate your new story, some suggestions:

- Start with the words ‘The Truth is…. ” Describe as vividly as possible what will likely happen if you continue with the Old Story you have got. Face reality head on by connecting the dots.

- Don’t labor over every word. You will edit it later. Just get your initial thoughts on paper, quickly.

- Because your New Story packs a cannonshot of reality it will necessarily stir a lot of emotion (the more powerful the better)

- Your New Story should clearly reflect and connect with your Ultimate Quest in life. Anyone reading your New Story Should have no trouble connecting it with what you care most about.

- Your New Story should be inspirational for you when you read it. It must move you powerfully: move you emotionally and move you to take action.

- Your New Story should contain a strong message of optimism and hope that the change you seek will indeed happen if you remain dedicated and persistent.

- Make sure that this is your story, no one else’s! Be sure this is what you really want!

- If possible craft your New Story in the context of a major turning point in your life. This change you seek should be characterized as a breakthrough.

- Work hard to summon your voice of sincerity. Your inner voice must be able to express the message, content, and direction of your New Story completely and unambivalently.

- In your story aim forward your best voice of passion. These voice can’t come forward without your encouragement.

Step 6. Design Explicit Rituals that ensure your New Story becomes reality

- Rituals are consciously acquired habits of behavior that enhance energy management in service of a mission

- Rituals represent the vehicle by which your New Story receives the investment of passionate energy

- Link the ritual to one or more values

- Invest energy in it for thirty to ninety days

- Acquire no more than a few rituals at a time

- Create a supportive environment

- A particularly valuable ritual is to begin every day of your ninety day mission by reading your new story